Performing Dr. Servetus, performing Richard Armitage — part III

[Trying to figure out if there was any need to respond to the contradictory errors with which I have been charged, along with my concerns that this material is way too personal to publish on the Internet, and also way too “replete with very thou,” have delayed publication of this part of the discussion for several days. But I don’t have time to futz with passwords for trusted readers, so be responsible. In the words of Mrs. Hale, “I thank you for your promise to be kind …”. I guess I can always poof this or compress it. If you are more interested in the Armitage narrative than the Servetus narrative, skip the long middle section from the picture of me to the picture of Clio. Strictures TWO and THREE from the previous post should be taken as read here. Remember that as a description of me, this text too is, alas, nothing more than another performance of self. So I’ll say with Puck, “If we shadows have offended …]

Andrew Lincoln and Richard Armitage attend the premiere of Chris Ryan’s Strike Back at the Vue West End cinema in London. The darling nose shows up delightfully in relief against Collinson’s hair. Makes you wanna play “I got your nose!” And it’s another abbreviated upper lip sighting. Yum. Also love how those curls at the nape of the neck and the slight disarray in the strands of hair, along with the lines around the eye, humanize the figure — underlining a successful performance of the Richard Armitage role here. Source: Richard Armitage Net

Previously on “me and richard armitage”: In an initial post, I argued for the impossibility of meaningful “real” knowledge about Mr. Armitage based on what he says about himself in interviews. In that same post, I noted the attraction of the hide/reveal technique of giving out pieces of information about himself that strands us between optimistic and skeptical stances toward what we read about him. Finally, I mentioned that any possibility of us obtaining such knowledge from interviews would have to be rooted in Armitage’s connection to and mediation of (his) stable, knowable self. In a second post, I argued that believing that it was impossible to know anything about Armitage based on what he said in his interviews did not imply that he was lying, and argued that in his interviews he is performing the role of Richard Armitage. I also rehearsed the reasons for us to be skeptical about the possibility that anyone has a knowable, stable self, concluding that the act of performing any role changes the self, and that this is also true when perform our own selves. This circumstance, it goes without saying, also applies to Mr. Armitage.

In the penultimate installment of this particular project, today, I want to give some examples of how performance of the self destabilizes and restabilizes some identity elements, focusing in particular on the question of performance in relationship to truth / ethics / genuineness. In doing so, I start with a (B) strategy, assuming –problematically– that I can describe myself accurately and arguing on the basis of my own experiences of performing the self. I point out the ways in which those assumptions have historically forced me to question the stability of myself in terms of (C), conditioned in my case particularly by the form of the expectations of others, an experience that draws into question if I can really describe what it is I am performing or experiencing or successfully perform or experience a coherent self. The shattering of this project, I conclude, leaves us as humans unable to know or describe, but left at (D) in the form of an inability to center the self that keeps us performing. Throughout, but especially at the beginning and the end, I relate my experiences to statements made by Mr. Armitage that index his own steps in delineating the role of Richard Armitage. The end of this segment concludes that these inevitable performances can be, and in the case of Richard Armitage’s performances of himself, plausibly are, deeply ethical. How Armitage accomplishes that will be the subject of the last segment.

***

III. Reasoning through Narratives

Mr. Armitage has been engaged in professional performances of various kinds since he was a teenager, so he’s been involved in working out questions of self from the moment of his earliest adult socialization, perhaps before he was even entirely aware of them. His statement about what he learned in those venues: “It… instilled me with a discipline that has stood me in good stead – never to be late, to know your lines and to be professional” points to an important aspect of performance — putting one’s own needs and desires into the context of the goals of the ensemble. He has noted that he finds exploring the relationship of person to environment a key tool for developing a character. In the Vulpes Libris interview, in response to a question about his practice of writing character biographies, he’s quoted as saying, “the moment when it comes alive is when that research turns into the character, and that character goes out into the big wide world and collides with other characters (often the facets created in the biography are designed to cause chaos when this happens, like planting a few explosions inside the character). … I like the interaction of a scene with another character. That’s why you will never see me in a one-man show.” This statement tends to suggest that he sets up his characters to experience the problems consequent upon the collisions between aspects of the self that occur when it is confronted with the other. Because of this statement, I tend to read his performances as attempts to explore such issues; he made similar remarks about John Porter ( I can’t find the quotation now) and I think that this theme goes even deeper in the script than his awareness of the inability to resolve the individual soldier vs. military organization theme at the basis of Porter’s moral conflicts.

The future Dr. Servetus at age 12, just as epistemological heck was breaking loose, which is fortunately not visible in this beginning of the school year photo. Breasts and orthodontia, which would be, appeared in the picture the subsequent year. I can faintly see the musculature of the avid clarinetist around the mouth. I was at my adult height (5’8″), and in contrast to Richard Armitage, I feel like this conferred all kinds of advantages. Then again, I wasn’t male, or 6’2″, and it didn’t all happen in one summer. Source: Mom’s (dusty!) closet.

The problem of the self-contradictory aspects of the self brought into sharp relief as a consequence of contact with others has been a defining one in my life. So if he’s setting up his roles to explore self vs. other issues, part of their attraction to me stems from my experience performing the self in various ways since I was a girl. Given the circumstances of my childhood, I have been troubled by the paradox that a lot of it has occurred in religious spaces. The devotional practices of the church in which I was baptized were designed to create a coherent self, to iron out potential contradictions by forcing the person to confront his irremediable tendency to sin through rigorous self-examination. I did those things. At the same time, though, as a precocious musician I was expected to provide musical accompaniments of various sorts to religious services. And as a child / teen heavily involved in church and thus perceived to be particularly pious, I also provided readings, etc. It was relatively clear from the beginning that these endeavors were not about my religious feelings; they were about creating or inspiring religious feeling in others, and in order to be successful, certain elements were required, in particular a level of concentration on sequence and execution that interfered with the development of that religious feeling in myself. In instrumental music I still found a shield between myself and the audience, something to hide behind, something else that it could all be about, some physical space where I could bivouac and find myself during the performance, but when it was singing or reading a text, I experienced no buffer. The immediacy was practically unbearable, so that the self as I performed it became the shield. The performance comes from the self but it must simultaneously bare and extinguish it while creating something new.

I couldn’t have put that process in words as a teenager, but as one of the most stunning but frightening texts I read in college taught me, the performance of faith extinguishes it, even as it creates something entirely different in one, a conviction that one must go on performing for the benefit of others. My unconscious but growing awareness of this problem was really jarring. By the time I was 14 I was suffering emotionally from the extreme struggles necessary to maintain the self I was performing in church and in musical venues. In the atmosphere of other family problems, no one noticed mine, thus perhaps guaranteeing that they would persist for years, but this experience makes me sympathetic in general to Mr. Armitage’s statements about having attained his adult height suddenly at age 14 and feeling something other than what people around him perceived him to be. (This has to be an experience that, mutatis mutandis, many of us share with him. The moments of early adolescence when the body begins to change in unfamiliar, indeed unrecognizable ways, and when one begins to differentiate from one’s parents, offer myriad opportunities for highly similar experiences to his, and mine.)

Leaving home at 18 thus came as a huge relief, since it meant that I could stop doing what I had increasingly regarded as playing games with things that really mattered but not being able to discuss the problem with anyone; I still participated in numerous music ensembles, but only in large groups where I was well-hidden, my self subsumed in a larger sea. Eventually, by grad school, I stopped playing music for others altogether; my doctoral adviser told me it would take necessary time away from work, and indeed, it seemed too much of a cheat. I couldn’t give up G-d and religion –that was too much to ask– but, looking back now, I see that in college I quickly exchanged the religion of my childhood for one that insisted less on access to a real, coherent self for one in which intent is still important but performance is thought to have value in its own right. Again, I wouldn’t have realized that at the time.

I came head-on with this problem again when I moved to Germany. Due to a surprising political situation that had suddenly influenced immigration patterns, several provincial towns were flooded with people of my new faith for the first time since the war, and qualified people to lead religious services were lacking. Despite my gender, as a competent lay person, I was quickly coopted into leading weekly services. Even though we pray all facing in the same direction, so that the congregation saw only my back, what I discovered after about three weeks was that the very reason I’d been pushed in that direction — that I appeared to my fellow congregants to be spiritual, pious, connected to the divine while in prayer — meant that I would never experience closeness to the divine again in that setting. Leading services was all about creating a feeling for others that I was excluded from because I was concentrating on creating it (which involved timing, singing, pausing, and giving stage directions to the congregation in the three languages of its members): and the most important component of creating it was the exercise of “being real,” which really meant “appearing to be real to the congregation.”

I was pretty good at appearing real to other people, and for a while I kept myself afloat financially by leading services for liberal congregations in provincial towns, but when I’d complete a service and then be expected to socialize with people afterwards while still in the role of the prayer leader, I’d be flummoxed. That role was not something I could perform at a dinner table, but what people seemed to expect was a version of that intensity and what they thought of as that “realness” sized down for interpersonal encounters. Even more disturbingly, as I grew more fearful that I was not genuine, I found myself speculating about ways to make myself more so. In my case, this activity frequently focused on debates about humility; isn’t the mere attempt to be more humble, or appear more humble, a rather arrogant exercise?

The problems in this setting were mitigated to some extent by the fact that I was always speaking a foreign language, while praying or interacting, and if my prayers were potentially contaminated, I could still fantasize that in some sense my emotions at least were only real in English. But as my German got better, that rationalization worked less well. By year three of living in that language I had to concede that I was perfectly well able to express my emotions in German, as indexed not least by an increasing number of arguments with my (native German) person, who was a bit taken aback as the woman he had thought of as irenic and smiling suddenly became able to express fairly forceful opinions in ever more exact terms.

And even then I didn’t know if I was expressing my emotions in German, or if German was somehow speaking me. Richard Armitage reports that he was affected by dreaming John Porter’s dreams; I began to feel as if I were drowning when I began to dream in German, when indeed my parents and others I knew only as English-speakers appeared to me in dreams speaking German. I totally understand how being away from home in a completely different atmosphere and essentially living as a different person could make it difficult to stay in touch. It’s not just that one is busy, and working hard, and physically tired; it’s that the act of bridging to the self that one’s family and friends at home know is sometimes too arduous to contemplate. My mother reports that toward the beginning of my third year there they began to pick up a strange vibe from me, and thought they were losing their daughter.

John Porter (Richard Armitage), at the end of the dream sequence in Strike Back 1.3. Source: Richard Armitage Central Gallery

(Detour raised by the issue of Porter’s dreams: From the sacred to the profane: Watching Porter’s highly scripted sexual fantasies about Danni in Strike Back has roused certain sympathies in me for the actors. Their job is to arouse arousal in their audiences, and for that, I assume, they have to both suppress any serious lack of sexual interest in each other in order to perform, but at the same time exclude the possibility of arousal for themselves in order to be able to perform. That’s a killer project for an afternoon; it must be exhausting to find a place to stand in that morass of contradictions while you’re getting naked with someone. It’s fun to fantasize about being Shelley Conn, but it’s exactly not the situation in which one would wish to find oneself kissing Richard Armitage.)

(Now back to the sacred). Appearing to be sincere: a contradiction in terms, one that I’ve started calling “the sincerity trap.” At the time, the elder sister of my person was teaching homiletics (the art of preaching) in the theology department of a German university. One of my research areas is the early modern history of homiletics, when very little instruction on the rhetoric of preaching was available to prospective pastors, and when I asked her what she thought the hardest thing was to teach the students, she said essentially that the hardest problem was the dilemma of being sincere while performing sincerity; that is, that the students didn’t understand that their actual sincerity wasn’t always perceived that way by the congregation, which expected sincerity from the pulpit. Most candidates for the ministry are sincere or feel themselves to be; but they needed to be helped to see how to bring that across to their listeners.

You can see through reading all of this why poststructuralism would have been a reluctant but consoling refuge for me, I think. Even as we grasp for the self, it flees our control. We think we have one self, but we have many; the people who surround us perceive another and in treating us as if that self is real, they either make it solidify or change us somehow. It would be one thing if we could plausibly decide who to be, but even as we find and perform one self, the performance changes the text we are performing. (Poststructuralisms would tend to suggest that all of these problems may be effects of the aporias at the center of language; I won’t explore that here, but my severe awareness of this problem after years of Bible study is the source of my obsessive speculations about whether people exist, which are fairly acute in the case of Mr. Armitage. A matter for another day, since I know most readers consider that possibility absurd.)

My searches for a self all ended in fragmentations. I didn’t become a musician; I didn’t join the clergy of any faith; I decided to take refuge in critical analysis of the human past and got a Ph.D. If I couldn’t be whole myself I would at least be able to understand and explain why I couldn’t. To some extent this choice was also a taking refuge in a facet of my personality that had been relatively consistent through all of the years and both religions and thus a desperate attempt to cling to trait that was relatively stable, if unattractive: a defensive stance that one elementary teacher termed a morbid capacity for and preoccupation with detailed observation–a tendency that may have created my problems in the first place. But the field of study I chose was the past of my childhood faith, which in turn –almost unavoidably– put me in the classroom. Here I was confronted with all of the problems I had before, though at first they seemed less threatening than in religious venues.

Clio, muse of history, as painted by Vermeer; perceived by me as a less threatening arbiter of my sincerity than G-d. Source: Wikipedia

It seemed to me at first that history lectures, being about subject matter, did not have to be about the communication of either sentiment, virtue, or truth. But negotiating those issues after they reappeared –exciting the students, encouraging them to define virtue and follow it, trying to convey an ethic of curiosity about the world that would spur them to seek out the truth– turned out to be much less problematic than the essential nature of performing Dr. Servetus before them three times a week. I was back in the exact same situation I’d been in front of my congregations; the only difference was that G-d was not involved. I thought maybe that would be the decisive thing to make the sincere performance of self that stands at the core of enthralling university lecturing possible. If I slid into “mere” acting, into what I’ve previously called pretending, at least it would not involve moral error. Even so, performing –in the sense of changing something, of achieving a completion– did not lose its fundamental nature.

After a decade of performing Dr. Servetus, I now have more available toolkit to deal with the challenges of performance, insofar as the techniques of performing and teaching are similar, and sometimes they are. For instance, even if I don’t learn lines, I plan what to say and how to say it, and I do need both to rehearse and to memorize; these days I have to have a carefully planned audiovisual element. Like Mr. Armitage, I warm up (though not with the Alexander technique; I do things I learned in singing lessons) before speaking to keep from overtaxing my voice and to fine-tune breathing and breath support to make sure I can reach the back of the hall for the whole 75 minutes. I think about my own stage directions, pacing, timing, etc.; and, as in the case of live acting, I respond to the dynamic of the lecture hall. When it’s all working –all the technologies of media and self are cooperating– it feels like I am not pretending; indeed it can feel as if my lectures are a performance in the way that the religious services I offered never were; it is in the lecture hall that I become able to believe in the self I am performing, as opposed to pretending for the benefit of others. Pretending is hard, even exhausting; performing (when it works) is easy. And the actions I take there are for the benefit of others, to try to help them understand how knowledge can change them. But it is also in the lecture hall that I am changed by my performances, that what I learn there changes me. In the lecture hall, I re-enter that yearning for the coherent, unitary self that I have in principle rejected the possibility of, but need to try to re-constitute for the students, and maybe for myself as well.

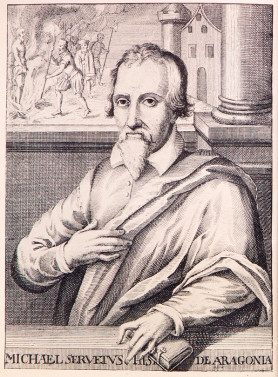

The historic figure Servetus, in an image from approximately a century after his death, someone with whom Dr. Servetus, as a Trinitarian heretic, identifies intensely. His thumbs and fingers are nowhere near as cool as Mr. Armitage’s, unfortunately. Source: Wikipedia

This process of change starts with creating the character of Dr. Servetus. Lecturing is another attempt at reaching the self and presenting it on an ethical–because hopefully honest or at least non-deceptive–level to an audience. Because it is deeply personal, rejection of the performance in whatever form that occurs is painful, even if it’s clearly a minority position. Cf. Armitage’s comments on reading about himself on the Internet: “The problem with me is I read everything, but it’s only the bad stuff that stays with me. It’s weird, you only need to be told something once and it stays with you.” Same for me: if I put myself out there, the rejection stings. As much as I need to read them in order to improve my work, the one angry course evaluation in a stack of a hundred ruins my mood for days. I could also apply this insight to the performance of self that is blogging.

More importantly, though, lecturing as an attempt to perform the self for the students points out the many flaws in what I think of illusorily as my core self, the self I am when I think no one else is watching. Some of those traits are good, admittedly, and easy to put out there: My intellect spurs students to question their assumptions; I can be generous with praise; I am actually funny in the classroom if nowhere else; I appear transparent and I tell them what I think if I am asked directly, at least within certain limits; I teach as if I am relatively uninvested in my own opinions; I appear irreverent; if I feel a side in a student discussion is losing unfairly, I argue present the most convincing arguments I can as advocatus diaboli.

As many of the necessary traits of a professor as I possess, however, I am lacking in important qualities of the good professor — patience, discipline, consistency. I’ve whined in the past about some of my failings, revealing others in the process. All of these positive traits have to be trained and added to Dr. Servetus’s panoply of tricks for dealing with students, and the negative ones suppressed. Cf. what Mr. Armitage says of creating John Porter: “It was a ‘challenge’ … to live up to Ryan’s character. ‘I wanted him to be the kind of bloke I’d like to be even without the flaws’.” In the interview in the DVD extras for Spooks 7, Armitage speaks similarly of Lucas as a super-hero and how he’d want him to be — better than himself. Similarly, I want Dr. Servetus to be a superhero professor. What I note about performance –how could it be different?– is that performing a better self can make me better. Attempts to be patient by performing patience in turn make me patient. Attempts to take students more seriously by performing taking them seriously in fact make me take them more seriously and improve their work because they think what they think matters to me. And sometimes, this whole process means that it does. The performance thus serves an ethical end: it serves not only me by making me a better professor, it serves the students as well. What’s become puzzlingly clear to me in all of this is how damaging “being real” or authentic could be in this atmosphere. What reasons would I have to become better, if I were only seeking to establish my identity? Dr. Servetus’s identity has to be the one that best serves the audiences of Dr. Servetus.

My concession that my “real” self, or at least the one that precedes attempts to perform the Dr. Servetus role, could be damaging to the students notwithstanding, I’m still bedeviled by the sincerity problem, by the dilemma of appearing to be sincere that challenges young pastors in new pulpits. My willingness to weigh every side of a questions sometimes appears to students as an unwillingness to take a stand, as wishy-washiness. Students want professors who are passionate, interesting; once one has appeared that way in a few lectures, one’s no longer allowed a bad day. Some days I have to try to perform sincerity, and on some of those days, it doesn’t work and remains a pretense. On a day when I can feel the different gears of the performed self straining against each other rather than clicking smoothly together, I can also see the students nodding off or reaching for their laptops. But on a day when it’s good, it’s a bit like what Mr. Armitage describes in his discussion of attaining confidence when he says, “I lost control and became the character,” or in 2006, when he was quoted as saying “Live acting is a kind of adventure sport[.] … “I don’t go abseiling or snowboarding, but I sometimes think that stepping out on stage can have the same kind of adrenaline rush.” And on a day when I succeed in performing sincere Dr. Servetus even when I don’t feel that way, I feel rewarded by the sense that such action has an ethical value.

I, like Armitage, confess to a certain amount of doubt about my performances, not least in the price I pay for them. It isn’t always equally easy for me to believe in Dr. Servetus. It was particularly hard this year. In the same 2006 article, we read, “Armitage admits to doubts about becoming an actor. ‘I regret it a lot,’ he says, furrowing his brow. ‘And I don’t know why, because when it’s good, it’s great. But it can take its toll on your emotions’.” As he notes, John Porter didn’t just go away after he was done playing the role; that can be a positive and negative effect of performance, I find. In a similar vein, I found interesting his comment: “I am searching for a place where I can just be, not necessarily a physical place, to settle down, a state of mind. I like to get home to Leicestershire but I rarely have much chance. Time seems so short.” I could parse this comment for days, but I’ll limit myself to noting that the unsettling effects of performance, as rewarding as it is, eat up hours of recovery. It’s not just the time it takes to get somewhere, it’s the time one needs to get in the frame of mind to go, to readjust the self one is performing for the new environment. If Mr. Armitage finds that issue both fatiguing and unsettling, well, I can only agree with him. It’s just that which may make the performance of the role of Richard Armitage both necessary and life-altering for him and us. Whatever it is, it’s not pretense. When he’s performing Richard Armitage, he is emphatically not pretending.

I hope it is clear now why I think there are certain kinds of performances of the self that can change the world, in that they change their audiences along with the actor, and I think part of what attracts me to Mr. Armitage is my belief not only that his performances are among these, but also that he may be embracing such performances as an ethical solution to the problems raised by the sincerity trap. I’ll pick up there soon.

Tour de force. I love it that this started as a fangirl site and is evolving toward a meditation on self and performance.

LikeLike

Thanks, didion. Well, you know what happens after you watch a certain film, oh, say, 40 times in a semester ….

LikeLike

Please may I respectfully suggest that:

1) This is YOUR blog. Those who are intrigued and challenged by the issues YOU raise, will continue to visit and comment. Agree/disagree. Without personal attacks.

2) It is your site. Block, if you deem reasonable, any who visit to change the tone to unpleasentness, rather than to reasonable discourse. This brings us to freedom of speech issues, of which, we are having some debate in this northern country. This your blog.

3) At the risk of having someone drop a bookcase on my head, I would say, proceed as you see right for you. Your commenters will drop off, if they don’t relate what you are doing.

4) For the record, I reached adult height between 12 and 13, (5 ft. Never felt it a “disability”, except for reaching shelves – what’s a stepstool for? :), and one of my oldest friends is 5’10. and she never thought that a disadvantage, either.)

5) Publish and be damned.

Cheers, and keep on blogging, please.

LikeLike

Thanks, fitzg. You are right, of course!

I can’t stop now that I’ve come this far. It’s become an emotionally necessary activity for the moment anyway, not least because of encountering such supportive readers. Thanks.

LikeLike

Reflecting on this more, I think that part of my reaction is that I have a huge investment in freedom of opinion issues in the classroom. That is — I am troubled when I read accounts of professors accused of insisting that students embrace their opinions in order to do well in class. I have to be extra careful because of teaching so much religious history, as the freedom of opinion issues intersect with freedom of religion issues, but there’s more to it than that: specifically I learn a great deal from people who disagree with me. I actually want to read disagreements and corrections, especially ones that point to holes in argumentation. I thus don’t want to see myself as suppressing contradictory opinion. It’s just that allowing that inevitably opens up the possibility of someone expressing the opinion that Servetus is a jerk. Which I try very hard not to be both IRL and on the blog. 🙂

LikeLike

Dear Servetus-

Since I gather that you are getting some critical responses to your blog, I thought I would tell you that I think it is provocative and fascinating. I don’t think you should alter your approach in any way.

Participatory media has transformed the ways in which both celebrity and non-celebrity identities can be performed, and I don’t think that we have even begun to understand what this means. This is what I take to be your project in writing “Me and Mr. Armitage,” and it is compelling to me for two (main) reasons: Richard Armitage seems to think very seriously about the construction of his diverse personae and–almost as a historical accident–his performance of celebrity has emerged in a direct and highly charged interaction with a complicated and unusually intellectual fandom (the so-called Armitage Army) whose interpretations and representations of the Armitage personae often compete for billing with his authorized ones. His well-intentioned attempts to communicate with his fandom from a putatively authentic identity or propria persona almost inevitably had to morph into the metacritical and definitively fabricated voice of the “Spokesperson,” who began to advance his own interpretations (and misinterpretations) of the “real” Richard Armitage.

It’s all very entertaining and thought-provoking. Since I am no longer an academic, but an administrator (my own resistance to performing the role of professor led me in a different direction than yours although I identified with almost all of what you wrote in “OT: On Whining”), I will let you sort out what all of this means, Servetus. I look forward to seeing where you take this.

LikeLike

Thanks, grayspoole, and welcome. I’ve gotten some vicious email so a positive response is always gratifying!

I like very much your comment about the intentionality of the early messages (made by someone who was presumably raised within a canon of politeness that stressed gratitude to people who praised him, and who perhaps had life experiences that tended to enhance his gratitude for the fandom’s development) vs the metacritical statements of the “spokesperson” and the inevitability of that transformation (made by someone to whom the increasing absurdity of his situation both as interpreter of himself and observer of the media had to be obvious). I think that text is one place where we most clearly see what I think I am talking about here — another is in his occasional performances of sarcasm. (I find these sympathetic because sarcasm is one of my own favorite refuges and I enjoy the sort of open-mouth response of people who aren’t sure whether I am being facetious or not.)

Your comment also points out (and Skully, a frequent commentor on this blog, would agree) the necessity of more analysis of the quallity of the fandom and the nature of its interactions with its object. I haven’t considered much the participatory aspect of the media on the blog but I think about it a lot with regard to the development of fanfiction about Armitage’s roles. Almost all of it, I think, can also be read as (mis)interpretation of Armitage himself. It’s amazing how much very complex, sophisticated fascination his work has generated — I don’t want to say that the results of this are more numerous than those of other actors, but they are (I think) much more sophisticated. In order to consider the fan side more fully, I’d have to participate in some of the fan forums, and I haven’t gotten to that.

I look forward to your help in sorting these things out — your comment is much appreciated. And who knows how much longer I will be an academic? 🙂

LikeLike

First of all grateful thanks to you Servetus for providing such a thought-provoking blog. Please, please don’t stop – it’s immensely enriching and mind-altering.

I’m finding it so helpful for my own near-obsession with RA to see the process of interacting with his persona(s) put in a context and so intelligently dissected. There’s something very soothing about being led by you through the layers of possible meaning in such a measured, unblinking and generous way. I’m now beginning to get a sense of what fascinates me about this man’s performances (in all arenas), and how they hook into my own (and others’) thoughts about identity. It makes me feel a whole lot less, well, fragmented!

From your initial post I now see that when I read an interview with RA I start from point B. But then some of his comments in particular go on sifting through my brain until I’m hovering nearer point D. These are the comments that tend to leave me feeling vaguely troubled and uncomfortable. And entranced as I am by the duality and ambivalence he invests his roles with, the drama that grips me most is the one (strictly in my fantasy, I hasten to add) of his own possible duality and ambivalence. The imagined struggle and conflict of trying to protect his identity while putting some version of RA out there has been, in my head at least, epic stuff.

I’m so glad you highlighted his comment about ‘searching for a place where I can just be’ – that has lodged itself in my brain. I’d love it if you spent more time parsing that one! Sometimes Interview Richard does seem to be bandying tropes around (Nigella Lawson, food etc), but at other times he does seem to be using interviews to process his changing views of himself – introspecting out loud. Presumably that’s why it’s all so engaging.

Here’s another comment that stayed with me, from the Allison Pearson Daily Mail interview:

‘I don’t think actors need to go on pedestals. I don’t buy it,’ he says. ‘I think it’s a weird thing. It’s like you become someone else, like stepping into another universe.’

It’s an odd complaint coming from an actor, whose job is pretending. But then Armitage has pretty ambivalent feelings about acting. He gestures at the bustle of activity going on all around us.

‘I look at our crew and I sometimes envy all of them – I wish I was a focus puller or a lighting technician. Part of me can’t work out why I’m still the gimp. I actually want to be the puppet master.’

That word ‘gimp’ bothers me, and I’m still working out why.

LikeLike

You paid me the greatest compliment without knowing it, feefa, by using the words “unblinking and generous” in the same sentence. Those are two of my biggest aspirations in the Dr. Servetus role, and they come out of a place far deeper than that role. Thanks more than you can know.

As you saw, I also read the Nigella Lawson comment as an exploitation of a trope — as much as I deeply wanted it to say something real about him, given my own generous figure.

I am also pleased that you pointed out these comments from the Allison Pearson interview and I think “introspecting out loud” is right on. After all, if this is a role he is playing, it is one that he only plays in interviews (since he plays different roles with family, colleagues, friends, lovers, etc., etc.), so interviews are a prime opportunity to try on a different version of the self he performs for us. Even so, I think it’s astounding that he would say such things and that they would make it into print. (I also think it’s because of statements like that that people tend toward a [B] reading of Mr. Armitage — they think that no one could or would possibly say such things and *not* be genuine in “meaning” them — the “not liking to wash” comment belongs in this category as well, I suspect, for many readers.) The word “gimp” bugged me a lot, too — because it sounded so resentful, which has up until that interview never been part of his performance of the role of Richard Armitage. It was either a dissonant element or an element that was enhanced/intensified from what has previously played in my mind as ambivalence about the personal costs of his work. I”m going to keep writing about this topic and some of the specific moments you mention above.

About the fantasy of his own possible duality — I have my own version of that as well. It’s entrancing, isn’t it? (sighs!)

LikeLike

There is so much you have presented to us in such an insightful manner that it will takes several readings to digest and be able to give an informed comment. My initial reaction is broken down into four rather cursory points, mainly beginning with p. I seem stuck on some alliteration treadmill when posting:

1. personal vs. private

You reveal quite a bit about your background which makes for exciting reading, but it’s used to illustrate your analysis and never feels intrusive or TMI

2. pretending vs. performing

As a teacher in almost daily contact with young people, this resonates particularly well with me. We all perform and yet when we pretend, we become worn-out. Sometimes other things in our lives disturb our equilibrium and the balance is shoved into “going through the motions”/the outer self rather than giving a performance which originates from the inner self.

3. pretty pictures

a)

servetus at 12, tall with glasses. That’s the age I started wearing glasses,too and I always felt they disfigured my face. It wasn’t considered cool to be a “four-eyes” then and the notion that I wasn’t pretty stuck with me until adulthood. Like Richard, I grew into my looks and get more compliments now than I got as a young adult.

BTW,I think you look nice here.

b) Two nice-looking men

I loved Andrew Lincoln in the series This Life when he played Egg, enjoyed his character in Love Actually and liked seeing him with Richard in Strike Back.

Richard: What can I say? I like almost any and every picture I’ve seen of him (not too fond of Philip Durrant or Percy Courtenay characters because of the pasty make-up). I’ve always loved how you’re able to analyse pictures, too, i.e. the way his hair curls, and his nose is in relief against Andrew’s head. It makes appreciate me the details even more.

4. Posters

@fitg, I’m with you on this one. We’d never persist with visiting a blog if we weren’t getting anything from it. You bring the cerebral side to the fandom. You wouldn’t want to let Richard down in his assessment of his admirers, “rather well-educated”. Plus it’s hugely enjoyable, too, so please let the good assessments of your blog stay with you.

LikeLike

Thanks for all the kind words, MillyMe; will definitely hang on to yours!

I think teachers (and presumably mothers) are really susceptible to this particular conflict because you just can’t be “on” all the time. Performing can be energizing but pretending can be exhausting. When you can get to a performance by starting the actions of the performance and then sort of falling or getting into it, that’s at least acceptable as a personal experience, but what I want in life are more of the self-extinguish performances and less pretense. I was just thinking that maybe professional musicians are the people who achieve that state most often, but then I realized I don’t know any professional musicians anymore. Hmmm. Anyone? Anyone?

the picture of me: I look at it and think both “you were nicer-looking than you thought you were” (I got kidded a lot about the glasses, too, but everyone who had glasses then had those awful frames, lol, and I was taller than most kids until the end of high school) and “you badly needed a haircut.” Looking back now I think my mom wasn’t paying much attention to our appearances at that point; she sunk into a low-grade depression after my brother’s birth and we were right in the midst of it at that point. So she wouldn’t have been thinking about haircuts, and my father wouldn’t have seen that as his job.

Lincoln: I loved that role in “Love Actually,” loved how it was scripted and adored how he played it. Haven’t seen him in anything else, but given that film was really sort of floored to experience him as a villain. I thought he did a good job, but partly because Collinson is such an ambivalent, opportunistic villain. He’s not evil through and through; he’s self-interested, which makes him understandable if not entirely sympathetic.

LikeLike

I can relate to much of this – childhood immersion in one religious tradition, including performing instrumentally and vocally, adult conversion to another less emotional, more catechetical religious tradition, living abroad as a transformative experience, etc. Sometimes I ponder if I would have been happier just to have stayed local and unexposed to so many of the ideas I’ve had to process. I also wonder if intelligence is inversely related to happiness as I have often found the process of self-examination emotionally excruciating. And yet I do not see how I could or would have made different decisions given the same circumstances. As a young person I was hungry to know the “other” and it was made available to me.

In any case, I no longer fit in with my original people (at least in some core beliefs) and never did with the people I studied. I am far more curious than most of the people I meet. I feel very much that I am an outside observer. I can, however, fake it almost all of the time. But in faking it I wonder if I am most of the time being false. Or if that indeed matters as long as the social intercourse is satisfying enough.

I wonder if my – our – speculations about celebrities’ being “real” is an expression of my own unease at being “false.” Also, it has been my experience that women are so often two-faced in social interaction. Perhaps women speculate about realness because they cannot believe – but they would very much like to believe – that someone is actually what they seem to be. And perhaps it’s not just a matter of attraction that leads to speculation about RA – it’s that he’s male. Would any us us spend any time wondering if a female celebrity – any female celebrity is real? I wouldn’t because I would assume that she is – of course she is – presenting what she thinks is most effective for the situation. It’s what women do.

LikeLike

I wonder about this question a lot, now, as I think about scrapping my profession, moving “home,” and doing something else with my life. Can I live there, knowing what I know now? Wouldn’t I be happier if, like my brother and sister-in-law, I had never really left home? I was dying to have the experiences I had and it never would have occurred to me (or my parents) that I shouldn’t leave home for college, shouldn’t live abroad, shouldn’t be curious about what was beyond the frontier. It’s just that neither they nor I anticipated the consequences.

I’m dying to believe that Mr. Armitage is who he appears to be. But it seems unlikely, given that I am pretty sure I am not who I appear to be, and that I suffer serious pangs of conscience for that. (Even as people I work with think of me as being brutally sincere … hah. If they only knew.) I think the only way around it is to accept that on some level he wants to be who appears to be, just as I want to be Dr. Servetus, and that that has to be enough.

And I agree I would never ask these questions about a female celebrity. I would assume she was acting. You’re absolutely right.

LikeLike

@Millyme & grep & servetus: you all express so much of my feelings, too. Is there something of The Other, as both women, and as living/have lived abroad, that resonates with us?

I can never regret having lived in other cultures, from England to Austria to Indonesia. Except perhaps, that it makes me a bit less satisfied with my country (which is is one of the best in the world in which to live) and just longing for the next trip “abroad”. Observers, indeed. Have lived long enough to just accept this.

(Have lived with glasses since I was six, tried contacts, and just prefer being able to see the face to which I am speaking clearly – besides, you can feel somehow “protected” behind the lens! Have to analyse that!) I can relate to RA’s nose, as I still don’t like my pointy one – think Allan a Dale.

Fortunate in that my family has been a traveling one; practically none of us born in Canada; we just can’t seem to stay put, though we’re 5th-6th gen. Canadian on the main side.

Is the feeling of “Other” just more pronounced in women? Or is it just as prevalent in “thinking” males, and perhaps in actors, who might perhaps be “observors”, too? Just throwing it out there, as part of discussion of identity.

LikeLike

I got my glasses when I was six, too, fitzg, also had a brief, painful experience with contacts, returned happily to glasses and I also totally see them as a device for taking refuge behind. Of course, I am also wildly nearsighted. My father detached both retinas this month, and I fear that is in my future.

Simone de Beauvoir would definitely have agreed (in _The Second Sex_) that the status of “other” is the definitive experience for women. I think that as gender roles start to change, though, her categories may break down somewhat (don’t hit me, didion!). And: and I think most of his interviews signal this — Mr. Armitage has often felt as if he occupies the place of “other.” grerp referred to this in a very penetrating discussion about the role that the teenager experience of humiliation might have played in his life, here, toward the end:

LikeLike

I think a quote from Strike Back is particularly apt at this point, spoken by Collinson (Andrew Lincoln) in the final episode: ‘It’s not what you are, it’s what you appear to be!’

LikeLike

You’re so smart, kaprekar … that quote was totally in the back of my mind while writing this and figures in the current draft of the final installment of this post. I’ve begun to suspect that Mr. Armitage will take certain roles based on scriptings like that one. Collinson delivers that line, and Porter immediately runs at him in rage. It’s like a sort of categorical denial of everything that Porter believes in. It’s one of the most sympathetic scenes in the film to me, as having a superior first betray you for his/her own ends and then laugh at you for your supposed naivete is, well, a chilling experience for me.

LikeLike

Now the use of that quote is worth analyzing too.

I am a bit at a loss of words, what comes to mind is an onion with it’s layers one peels off. In any case I am still processing this post. Personally I appreciate the risk you took revealing so much of yourself. In return it’s helping me in my journey with identity.

LikeLike

What nice things to say, iz4spunk. I’m touched to have been of any help, as I feel like my own journey has been so meandering.

LikeLike

servetus, time is limited at the moment but I want to say that I’m really really shocked to hear that you have received ‘vicious’ emails. At least you can use the technology to block future offensive communications (or at least some of them).

LikeLike

Servetus, I visit your blog regularly and I love it. Your mind works so differently from mine (I am more a beta person, that is what science is called in the Netherlands), and I don’t really analyze texts, history and the self in the way that you do, nor can I to be honest. So I am loving it that you take me by the hand so to speak, and let me experience this journey with you.

I also have lived abroad a couple of times, and feel an ”other” in my own country. As such, I am touched by Lucas North, who says that home is where people understand you, and not just where you live.

LikeLike

Hi,

I’ve been lurking on this blog for a couple of weeks ever since I discovered RA via Vicar of Dibley and then North and South.

I had to respond to this post because I read the whole thing :).

You remind me in some ways of myself when I was younger although our styles are different. I have always considered anything that obsessed me or touched me a fertile ground for exploration, discovery. It’s never been important to defend it no matter how shallow or trivial it seems to others; for me, it has meaning and in interaction with the entire phenomenon, I am changed and the world in effect changes in some way. I have a great curiosity and a need to understand everything and I adore the intense analysis and passion that obsession or love bring to me. I like the big and nuanced questions and am a philosopher at heart.

This has certainly been my self consistently from the time I became conscious.

As to your post: I see the ongoing search for self. I do not agree with poststructuralism (I find it lazy) and there is no question that the personality/temperament is formed at birth. A good example of the latter is Michael Apted’s “Up” series. There is a consistent self, even if we don’t see it. I think that your choice of profession is consistent with who you are, not a “concession”, but more of a vessel, just as acting is the vessel for the expression of RA. Having doubts, and wondering about authenticity is longitudinally par for the course, in my opinion, and as always, it is part of the engagement with the facets of self and the dialectic that often ensues.

I was interested to read your experience of serving as a shaliach tzibbur (emissary of the congregation), and how that messes with a sense of self in the sense of expectations of piety. Having spent many years in daily minyan, one learns that piety cannot be extrapolated from the performance of ritual; some people are show offs. I think it’s the engagement with the characters in minyan afterwards that makes it all “real”, including oneself. I personally never looked upon the prayer leader as anything than one learned in some aspect of the religion, and a great asset for the rest of us, and simply, one of “us” (even if they were an annoying show-off).

How all this relates to you and RA (love the blog title!): I know a little about performance and RA is right- it is when you completely forget yourself, you find your self. And that self, your essence, cannot be grasped or articulated. Don’t you love the paradox????

When RA talks about the adrenaline rush of performing, I find it no different from any environment that allows one to elicit the self; at special moments it makes one feel so alive, a peak experience. You bring to those moments everything that you are, all your skills which are wanting to be further honed by some challenge. It’s a form of play. It takes an inner confidence to do that; on some level you know you can do it (sadly he doesn’t get enough challenges). When I say it ‘s a form of ‘play,’ I always think of Bach who composed within rigid forms, but the variations were infinite. Play is also fun.

And we do know Richard, as it turns out. Thanks to your post. He doesn’t seem very different from you or me (and some others) in his thoughtful approach to life and his art. He expresses it differently, but wants a similar outcome.

The few massive film crushes I’ve had in my long life have always been profoundly transformative, and they have been obsessions because they call to something deep within me that stirs, wakens and challenges me; what better way than to be triggered by beauty and passion and mystery?

A thought provoking and insightful post. Too much to respond to in one comment! Thank you.

LikeLike

pi, a belated welcome and thanks for this post, which meant a lot to me. I’m sorry I’ve let it rest this whole time.

shaliach tzibur: you got it in one. There were a lot of weird things going on in Judaism in Germany in the 1990s. Well, there are still are, but it’s settled down a lot as the non-Orthodox have gradually won more recognition. You had (a) a core congregation of people who were living away from the Jewish metropoles in Germany, such as they were, who were allowed to have lively congregations because of the immigrants, but (b) the immigrants had little to no experience with any religious, ritual, or liturgical elements of Judaism and so were drawing their expectations about davening from other areas, and you add to that (c) as prayer leader a convert to Judaism who had a neo-pietist Lutheran childhood and a decade of hanging out in Conservative shuls and chavurot. The nussach in German liberal congregations is going to be patchwork for at least another 20 years, for example, as it’s a combination of Israeli records, Camp Ramah, Lewandoski and various other things. If we could have gotten people to constitute a daily minyan some of these conflicts might have been mitigated, but that wasn’t realistic in that generation. It might be in the next.

I think poststructuralism can be lazy. For me it was a sort of last resort before giving up, a kind of paradigm for how to think about the possibilities of transformation. I’m disturbed by its moral implications, I think like most people are.

Oh, and my mom would totally agree with you about the formation of the personality!

LikeLike

Don’t actually find you “sarcastic”, servetues. Ironic, and on occasion, refreshingly “facetious”. (facestious is good – lightens the atmosphere! 🙂

Must re-read de Beauvoir. Any comment has been from memory.

A uniting factor of “RA fandom blogs” has been the stimulus to reading. “Lords of the North” is on order. “Sunne in Splendour” in the personal library. Think I’ll approach “Crime & Punishment” in small bites initially. Delicate digestive system :). Never much cared for Heyer, but maybe a re-visit? Re-reading all the Josephine Tey mysteris, beginning, of course, with “The Daughter of Time”. (and re-joining the Richard II Society….can’t wait for the first delivery of The Ricardian!)

LikeLike

And I still haven’t learned to properly proof-read on-line. Aaargh!

LikeLike

[…] of the ill-fitting suit as, at least initially, an index of the absence of glibness in his performance of self. I quote her: “Truth be told I miss the guy with the ill-fitting suit, long hair and shy […]

LikeLike

On the abandonment of ill-fitting suits: Or, Armitage resartus, part 3 « Me + Richard Armitage said this on June 13, 2010 at 5:38 am |

[…] in local beliefs and customs, though I live and work outside of these by my own choice. My work, which I also experience as a performance, is exhausting and all consuming and demands a period of “switch off.” Just as Armitage […]

LikeLike

Late thirty- or early forty-somethings together, or The Way We Live Now « Me + Richard Armitage said this on September 17, 2010 at 8:54 am |

[…] as she has said to me before in comments on another post, that Armitagemania is not a disease, that it can be a positive obsession, and she provides some helpful further information about that in the post. I really appreciate her […]

LikeLike

Bursting with Armitage-y goodness! « Me + Richard Armitage said this on December 19, 2010 at 10:33 pm |

[…] by May of 2010. It touches on things that I wanted to say in the never published part IV of this series and in the “Armitage barbatus” series and in the “tropes” post, all of […]

LikeLike

My Richard Armitage: An interpretation. Preface « Me + Richard Armitage said this on November 17, 2012 at 5:53 am |

[…] able to see him is also a role he plays for our mutual benefit. I’ve said this many times, from near the very beginning of the blog, but it may bear repeating. This assertion doesn’t mean that he is solely false but neither […]

LikeLike

me + Richard Armitage fan selfies: musings on self, presence, and the proximity question [a bit on evidence] | Me + Richard Armitage said this on January 27, 2014 at 7:48 am |

[…] That conflation is by the bye most of the time. Adopting this sort of pseudonymous identity has a creative, transformative quality, and Servetus has made it possible for me to do things I would not have imagined possible; most notably, starting to think of myself as a writer, and abandoning my role as a professor. On a more fundamental level, I think I realized fairly early into blogging here that once source of my deep unhappiness was that I was suffering from a strongly fragmented identity, that I had few or no real life friends who could accept all the incongruous things I am/was in combination: the Jew and the former Christian, the girl from the country who loves the city, the academic who reads trashy novels, the leftie who grew up in a conservative household and still believes many of the things she learned in that atmosphere, and so on. Nobody gets that, I think, we all dream of total acceptance and understanding, but nobody gets it, even from a parent or the most devoted lover or partner (and that failure may have advantages to it). And I have gotten a lot of acceptance here, maybe more than I could have expected or gotten anywhere else. But my pieces were so scattered that I was pretending all the time and being alone was the only relief I got from the act. What was even worse (and I sometimes still see this reflected in the things that former students say to me these days) was that people thought I was being authentic even while I was hiding behind a series of masks. Authenticity was itself a performance, which was something I tried hard to say about Richard Armitage back in the day. […]

LikeLike

Kingdom Come at Roundabout Underground + me + Internet friendships, part 2 | Me + Richard Armitage said this on January 5, 2017 at 7:47 am |