Mr. Armitage, his fans, our pursuit of “great art,” and me as critic, part 2

[Part 2 of this. I can’t believe this actually got longer than part 1 — when I originally got here, I thought, “oh, now you’re into the home stretch.” Snort. Discussions elsewhere including comments on the earlier post may have passed this by; I’m going to try to get to some other discussions as soon as I’ve finished formulating, and posting, this. If I didn’t link to your statement on one of these themes, please don’t be hurt; I may link retroactively if it seems relevant. There are five sections. You may not want to read them all at once. Or ever.]

[I also interrupted myself to go see “The Social Network.” Intriguing. You see, I do occasionally consume visual media in which Mr. Armitage does not appear. And I read books. All the time.]

[This is not as polished as I’d like, but I must make myself stop now. When hypomania threatens, as it has lately, it’s hard for me to stop working but I must if I am not to burn out all my synapses and thus put myself out of writing commission for indefinite periods of time. Perhaps I’ll revise later.]

***

To resume: The reasons I feel the way I do –thinking that it’s entirely justified and necessary to criticize his work, but that I’m not going to be advancing a critique of his professional “choices” on this blog– are myriad — and of course, as always, they say more about me than about him. That is the conceit of the blog, after all.

“Вьеточка, are you happy?” Lucas North (Richard Armitage) asks Elizaveta Starkova (Paloma Baeza) in Spooks 7.2. “Happiness isn’t about getting what we want, it’s about appreciating what we have,” she replies. “Someday, you will be happy, too.” Source: Richard Armitage Central Gallery. What would make Mr. Armitage most happy in his career? It’s up to him to decide.

“Вьеточка, are you happy?” Lucas North (Richard Armitage) asks Elizaveta Starkova (Paloma Baeza) in Spooks 7.2. “Happiness isn’t about getting what we want, it’s about appreciating what we have,” she replies. “Someday, you will be happy, too.” Source: Richard Armitage Central Gallery. What would make Mr. Armitage most happy in his career? It’s up to him to decide.

I. Getting work, actually working, and the identity of the worker

First, I am inclined to take the argument that one takes roles to keep working extremely seriously, not just for pragmatic reasons, although those are important, and despite the inherent risks involved in taking on the “wrong” role. For many artists and creative workers, work is not only something done to achieve a particular artistic end (although one seeks that) or product, but rather, and perhaps more importantly, a specific way of being in the world to which one is attached, sometimes inextricably. Painters sketch, even when they are not painting masterpieces; musicians practice, even when they are not performing; authors write, even when they are not publishing. Work is a discipline that helps to maintain the integrity of a particular kind of creative personality. And when one views work in this light, I suspect, not working can always be potentially much more dangerous than working at a troublesome task or ending up “typecast.” I read some elements of a similar stance in things that Mr. Armitage has said. (Keep in mind this is *a* reading. Not *the* reading. A description of how I read his interviews, not necessarily a description of how he really is. I remind all readers again that I have never met or talked to Mr. Armitage personally and am not claiming to have done so.)

Practically speaking: We don’t know what roles he’s being offered, and more importantly, which ones he’s up for but perhaps does not get, and the reasons he is not getting them. It would be interesting to know if he still regularly auditions for stage roles, for instance, given the commitments he makes in television contracts and possible options in them for future series, because the annual calendar for stage productions, given the constraints of the theatre season, could conflict with television filming. One wonders if there are also physical issues for him, as there were in musical theatre — for instance, if it’s a problem to be 6’2″ if the remainder of the ensemble is going to be 5’8″, which is harder to correct for on a stage than with a television camera. I could speculate, based on the severe difficulty he reports in obtaining roles early on in his career, that his auditions do not always present the best impression of his performance capacity, that as someone who superficial evidence suggests is an overlearner, he needs to live in a role a little bit longer to be most effective in it, and that auditions are based on a slightly different skill set: the ability to turn on a performance quickly and immediately. We just do not have enough information here to be concluding much. In the absence of that, however, he’s in the kind of profession where to obtain employment at all involves fortuna as much as it does virtù. Presumably, Mr. Armitage now has more options as to which roles he takes than he did a decade ago, and maybe he could afford not to have taken Strike Back or Captain America. But as jane notes here, his career is still not yet at the point where he has infinite options. In his job, the vast majority of talented people never, ever get the role they dream of. He’s an Equity member; although not all productions in the U.S. are Equity controlled, of course, and some people would say that union membership actually reduces the likelihood of employment, Actors’ Equity in the U.S. still regularly offers statistics of 85-90 percent unemployment among its membership. Relief over doing the voiceover rather than playing the spermatazoon is probably still regularly in his mind; there are roles much more frustrating than that of the legendary (which I will think of us as apocryphal until I see visual proof) dancing banana. I honestly don’t think that avoiding roles that don’t fit or even approach your ideal works as a general strategy for obtaining employment in your ideal role except for the very top of the A list of actors (though I wonder if Mr. Armitage would really want to be in that category, ever, as it typically involves a franchise role). It is, however, a good plan for the average and even the very talented actor if homelessness is his goal. Of course, the question arises about when enough is enough, when an actor has done enough work to be able to take a break without worrying about the consequences. Some fans think he’s at that point or near it, but he shows no sign of thinking this. Mr. Armitage’s eagerness to keep working and explicitly expressed difficulty turning down work is typically interpreted by fans as either ethical (he believes in hard work and earning what you get; he doesn’t want to laze around) or neurotic (he’s a workaholic, or he has a deep-seated fear that if he stops, he’ll never work again). I think both of those interpretations are reasonable based on remarks he’s made. But I also think the issue may move beyond that for him — who are we, who do we become, when we work?

Working in a profession with a narrow educational path and limited employment opportunities, I’m all too aware that in certain fields one can only take the jobs one is offered and that factors that influence job offers are heavily out of the applicant’s control. The job I’ve been in for the last decade was one that I would never have chosen for myself as I applied to graduate schools, as I thought about employment during my professional preparation, or even had there been other possibilities on offer that particular year. Saying that I would take it to keep working, try to like it, and then try to find something else while I had it proved illusory. It was as if by hiring me, my current employer got an option on all of my future performances anywhere, not only in the sense that it became difficult to convince other prospective employers with the kind of position I thought I wanted that I’d ever leave this one, but also in two other important ways.

The first is actually akin to typecasting — an issue that is acute in my life right now — and relates to external perceptions that I can’t shake that I am a certain “kind” of professor. My development in that “type” was actually underway from the very beginning of my academic career, even before I set foot in my first graduate class, though I didn’t realize it until it was put rather forcefully to me as I finished my dissertation. That doesn’t exclude the possibility that I am or could be different than I am now — but one’s potential ability to be the right person for the job is not the issue that prospective employers consider in situations where the reserve army of labor is huge and standing in line right outside the door. They want someone they know can do it now without any rehearsals. The second is that in having this job, in being in this atmosphere, I also have actually changed. I am not the professor now that I might have been had I gotten different jobs at the beginning of my career. (For the record, this is my third, and I’ve been exceptionally lucky — that’s two or three more than most people who finish a Ph.D. in my area have had.)

Now, one could argue that the way to avoid the twin problems of being typecast or becoming something other than the performer you want to be — in acting, as in academia — is simply not to begin by taking employment that one knows one doesn’t want. For various reasons, some young academics do just that, if they can say exactly what sacrifice is beyond their ability to make in order to start or continuing working in their chosen field. But it’s a hard argument to make to someone who has a really specialized training: you’ve finished a preparation that involves a giant commitment and opportunity cost on so many levels but if you’re not offered what you want, sit out until you are? (Perhaps I am unduly sensitive about this problem since I repeatedly sacrificed other significant things to pursue my career — but particularly at the beginning, the thought of not taking available employment would have been excruciating — as if I had wasted seven years of my life.) I think that argument is valid for settings in which a great deal of work is available, so that if you wait a bit for the right thing, eventually you’ll get the offer you want, and you won’t be committed to something less attractive just because you wanted to stay employed. But there’s another problem — the question of what people think they are “supposed” to do with their lives (to use a taboo religious word that certainly applies more to me than to Richard Armitage): their “callings.” Indeed, in modernity the devotion to work for its own sake is a secular form of calling, if you believe Max Weber. People who work in artistic and creative fields tend to have some form of this conviction in terms of understanding their particular talent as leading to a calling. It’s another personality factor that makes it hard to sit on the sidelines if work is available.

If you look at work in this way (and based on my own life experiences, I’d actually advise you consider trying not to do so if you can), you tend to think that there is one right end to your professional life — either by blessing or by curse. Mr. Armitage has expressed this sentiment repeatedly, indeed from near the beginning of the point at which he hit the public eye he said things like “there is nothing else I can do.” More recently, asked about how he stayed motivated during the long dry spell at the beginning of his acting career, he replied: “In that situation you spend a lot of time thinking about what else you can do. I tried other things but really didn’t have any other skills; if I’d have been good at something else I’d have been doing it already. You get to the point where you think: ‘I can’t do anything else and don’t want to do anything else either.’ That drives you.” This attitude indeed both drives and bedevils one, I think, and the result can be an odd sort of ambivalence about one’s experiences doing what one thinks one is supposed to be doing, an ambivalence that comes out repeatedly in Armitage’s statements, which wax between describing the incredible rush of acting, and the linked feeling of being out of control, a marionette suspended on wires, a gimp. It’s even more problematic if one’s not firmly convinced about things, as one continues (like Weber’s Calvinists) to look for evidence: “I’m a bit of an all or nothing kind of guy. To be honest, I had no blind faith in myself” in the face of the problem that one has to show patience (in the same interview: “The interesting roles have only come since I got into my 30s. But I didn’t know that was going to happen.” If you have the vague feeling that you are doing what you are supposed to be doing, you need to persist; if you are going to leave, you have to have a clear message about an alternative; if you are successful, then you need not to let that feeling abate. These are the sort of personality features that tend to keep creative people working even when perhaps they don’t “need” to to advance their careers or pay their bills. If it is what you’re supposed to be doing, what you have to do, something about which you have little or no choice, leisure is not really an option.

I’m also going to say that I suspect the content itself is secondary to the process of working for the creative personality. One happens to be skilled at producing a particular type of content — long, classical compositions, let’s say, or impressive performances in Baroque comedies — but the content is secondary to the practice of producing it. Artists — perhaps especially artists, in this age of mechanical reproduction — don’t get to decide all on their own what the content is going to be, or how their artistic identity is going to develop as a result of those decisions. An actor is never an actor without an audience, without someone watching a performance. But in turn the performances change one. One becomes more accustomed, more used to certain kinds of performances than others. We could view this development as a betrayal of talent, or a natural part of growing as an artist: exploring new things, accepting and becoming acquainted with new audiences, changing as a result of exposure to them and becoming something yet more different.

But I think, given the sense that many creative artists have about their work in relationship to their calling or creative ends, it’s probably wise for a driven individual who wants to use his talents wisely to escape the notion that there is a single, appropriate creative identity for him in his art, a single way to achieve the process of working. It’s the equivalent of the idea that there’s only one ideal mate in the world for each of us — that way madness lies — a recipe for constant frustration. Creative people work as a way of being in the world, and for the talented, the world offers many options for how to be. Not infinite ones: there are certain things that every artist won’t or can’t do. But nonetheless, working — no matter how “trivial” the role — can be a way of fulfilling one’s talent, and this is a process that one performs inwardly, that one judges primarily according to one’s own scale of values. That value set can be complex — obviously, no individual can completely immune to the conventional rewards offered via money and artistic recognition — but autotelic personalities will probably always be less motivated by these than by their own concerns. One suspects that this stance makes certain roles look very different from the perspective of the actor playing them than they do from the perspective of the audience.

I wanted to conclude with the platitude about how “there are no small roles, only small actors,” and when I looked up the source, I saw that wikipedia attributes it to Constantin Stanislavski. Well. That attitude would explain a lot both about Mr. Armitage’s smaller roles (one thinks of Ricky Deeming) and about the attention he brings to smaller moments inside of big roles. Every role, every moment in a role, can be pregnant with possibility. I think that’s why we watch him. Do we really want him to change that?

***

Richard Armitage as Claude Monet in The Impressionists 1.3. The “great artist” at work. Source: Richard Armitage Central Gallery. But what makes Monet a great artist? The vision? The execution? Or the franchising / product placement? Think about why or how you even know who Monet was. For most of us, isn’t it because we saw a mass produced product with one of his more famous works on it? A tote bag with with an image of one of the “Water Lilies” series paintings on it? Or because a teacher or professor told us it was significant and explained why?

Richard Armitage as Claude Monet in The Impressionists 1.3. The “great artist” at work. Source: Richard Armitage Central Gallery. But what makes Monet a great artist? The vision? The execution? Or the franchising / product placement? Think about why or how you even know who Monet was. For most of us, isn’t it because we saw a mass produced product with one of his more famous works on it? A tote bag with with an image of one of the “Water Lilies” series paintings on it? Or because a teacher or professor told us it was significant and explained why?

II: “Great art”?

A corollary of the problem of not getting “great roles” is the question of what that means for our evaluation of Mr. Armitage’s career. Assuming he could indeed choose between all potential roles available at any given point, and chose series TV rather than theatre engagements in classic plays or films that became iconic, would that suggest that he’s not a “great artist”? If he never plays Oedipus, Richard III, Lear, or some other comparably distinguished role(s), and twenty or thirty years from now, Lucas North and John Porter end up having been being more typical of his career than Mr. Thornton was, does that make him less worthy of our esteem as an artist? Does it mean that he betrayed his talent, if he had the opportunity to play Willy Loman or Douglas Hector and he turned it down? Was he then not a “great artist,” but “only” an entertainer?

All the scare quotes in this section probably make you realize already that for me the answer to these questions is definitely “no.” That response is based both on my interpretive priorities and on what I see as his strengths as an actor.

To some extent, this stance involves rebellion, insofar as I grew up with an unusually restrictive definition of the “art vs. entertainment” distinction. So indeed a part of me wants to say, just to be contrary, that the artistic contributions made in some series TV are just as significant as roles in canonical dramas on the stage or big screen. (And I think this is at least arguable: think, for example, of LeVar Burton‘s portrayal of Kunta Kinte in Roots, which rocked the world of many of that series’ viewers.) I no longer personally accept the art vs. entertainment distinction. That’s just me talking. Servetus wants to feel free to enjoy her mindless pleasures without guilt that she’s wasting time when she could (should!) be bettering her mind by reading Proust. (I never made it past The Guermantes Way, and everything I did finish I read in English.)

To some extent, this stance involves rebellion, insofar as I grew up with an unusually restrictive definition of the “art vs. entertainment” distinction. So indeed a part of me wants to say, just to be contrary, that the artistic contributions made in some series TV are just as significant as roles in canonical dramas on the stage or big screen. (And I think this is at least arguable: think, for example, of LeVar Burton‘s portrayal of Kunta Kinte in Roots, which rocked the world of many of that series’ viewers.) I no longer personally accept the art vs. entertainment distinction. That’s just me talking. Servetus wants to feel free to enjoy her mindless pleasures without guilt that she’s wasting time when she could (should!) be bettering her mind by reading Proust. (I never made it past The Guermantes Way, and everything I did finish I read in English.)

But I have scholarly reasons for drawing that conclusion, as well. The first is that the burden of intellectual and cultural history research in the last two to three decades has tended to reveal the heavy contingency of notions about what is “important” both in our own periods and in the past. An important demonstration of this conclusion is found in the work of Robert Darnton, whose study of actual printing practices and statistics in eighteenth-century France demonstrated convincingly that the Enlightenment texts that historians said for generations were central to the coming of the French Revolution were well outsold in the previous half-century by fanciful science fiction works and p*rnogr***ic pamphlets about Marie-Antoinette. Closer to our own times: of these two novels published in 1850, which have you read? Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, or Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World? The former is still considered so important that almost every college-bound high school student in the United States will be forced to read it in school; the latter could be characterized as a 600-page-long h/c fanfic without the c. But Warner’s book was much popular than Hawthorne’s, and probably as well-known in the mid-nineteenth century as Uncle Tom’s Cabin; both Jo March and Elsie Dinsmore read it. Ah, but Hawthorne’s work has transcendent value, you say, while Warner’s work appealed to the basest of cheap emotions and cultural stereotypes, and we read Harriet Beecher Stowe today only because the book was politically significant in mobilizing readers to support the abolition of slavery, not because it’s great art.

But who decides what is transcendent? Transcending what? History? I’ve read Uncle Tom’s Cabin at least ten times, starting in fourth grade and most recently in the summer of 2006, and Hawthorne exactly once, in my junior year of high school. Almost no one except experts listens anymore to the most influential music of the twelfth century, the work that spawned the return of Western music to polyphony and created a system of musical notation that was definitive for the next four centuries. It transcended time and space and I bet most of us have never heard of it. (I force my students to listen to modern recordings of it made in a historically accurate style and they cringe. Does that mean it’s not a classic? Or that it is a classic? Because it’s difficult to appreciate?) Do you think the music of Bach is transcendent? In his own lifetime, Bach was famous primarily as a performer rather than as a composer. His reputation did not depend on the compositions we think of as definitive today: the Brandenburg Concertos, the St. John and St Matthew Passions, the Goldberg Variations, or his many well-known cantatas. His oeuvre had been largely forgotten in the century after his death, until the so-called Bach Revival, when many of these works were “re-discovered,” but this rediscovery was driven not as much by artistic concerns about the timelessness of the music as by the ability of cultural movers and shakers to connect it with German Romantic nationalism, and the performances of it that were offered were wildly anachronistic, sometimes making the canonical works unrecognizable from Bach’s perspective. It took longer than a century for the works of Shakespeare to take on the uncontested “most important author of the English language” status they have today in the canon of English literature, that development was at least in part driven by the evaluations of writers and thinkers outside of England like Goethe and Voltaire, and even now particular works go in and out of style according to the tastes and whims of an age. When was the last time you saw Cymbeline? Yet it was quite popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. My point here is that no work of art really speaks as “a classic” to the sensibilities of everyone in a potential audience over all of space and time. It’s impossible.

But who decides what is transcendent? Transcending what? History? I’ve read Uncle Tom’s Cabin at least ten times, starting in fourth grade and most recently in the summer of 2006, and Hawthorne exactly once, in my junior year of high school. Almost no one except experts listens anymore to the most influential music of the twelfth century, the work that spawned the return of Western music to polyphony and created a system of musical notation that was definitive for the next four centuries. It transcended time and space and I bet most of us have never heard of it. (I force my students to listen to modern recordings of it made in a historically accurate style and they cringe. Does that mean it’s not a classic? Or that it is a classic? Because it’s difficult to appreciate?) Do you think the music of Bach is transcendent? In his own lifetime, Bach was famous primarily as a performer rather than as a composer. His reputation did not depend on the compositions we think of as definitive today: the Brandenburg Concertos, the St. John and St Matthew Passions, the Goldberg Variations, or his many well-known cantatas. His oeuvre had been largely forgotten in the century after his death, until the so-called Bach Revival, when many of these works were “re-discovered,” but this rediscovery was driven not as much by artistic concerns about the timelessness of the music as by the ability of cultural movers and shakers to connect it with German Romantic nationalism, and the performances of it that were offered were wildly anachronistic, sometimes making the canonical works unrecognizable from Bach’s perspective. It took longer than a century for the works of Shakespeare to take on the uncontested “most important author of the English language” status they have today in the canon of English literature, that development was at least in part driven by the evaluations of writers and thinkers outside of England like Goethe and Voltaire, and even now particular works go in and out of style according to the tastes and whims of an age. When was the last time you saw Cymbeline? Yet it was quite popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. My point here is that no work of art really speaks as “a classic” to the sensibilities of everyone in a potential audience over all of space and time. It’s impossible.

If a work can’t transcend time and space, what about a performance? This seems to be one of the lines pursued in some argumentation; people want Mr. Armitage’s performances to thrill later generations of viewers as those of the leading men of screen and stage have done. Actually, I don’t think that Armitage’s current position as a performer puts him in a bad place to have this happen even if he never makes a major motion picture. Historically the vast majority of all performances in all media by all actors up until the second half of the twentieth century were simply been lost except in the memories of their audiences. We know their names, perhaps, and their paintings or still photographs of them, and if spectators wrote down their impressions we know what was thought of their performances. But before the 1890s they were not recorded on media; negatives of 80 percent of silent films have been lost; the shelf life before disintegration of the media used to make films in much of the latter half of the twentieth century is about fifty years and much of this material is likely to be lost as well. In no sense can we say that important things will survive, as the definition of “important” is incredibly arbitrary and defined mostly by the judgments of posterity, thus inherently retroactive; the works of some of the most popular artists of the silent film era are completely lost. If we could see all of silent film and judge those works and performances by our standards, it seems we might be likely to choose to preserve some items that are lost, and our own notions of what is artistically significant in silent film might change substantially. Mr. Armitage is actually working at an interesting period in the history of visual technology, in that computers and digital version of productions may substantially alter the patterns that determine which works of film and television are preserved or disappear. It’s not that the new media are inherently eternal. They’re not, although some of them may be slightly more stable under normal atmospheric conditions than acetate film was. (A bigger issue is the machines that play them, which have a tendency to break down easily and change rather quickly these days.) I think what’s decisive, though, is that these media are potentially much more widely distributed and the segment audiences that preserve a particular work and pass it on, moving it from new medium to medium because it is important to them, are substantially more numerous than they were only a decade ago. The survival of Spooks is now not contingent on the potentially sloppy administration of a particular media archive somewhere; millions of legal and illegal copies of it are located all over the world. It’s hard to imagine that its transmission to posterity could be damaged in the way that the legacy of Doctor Who has been, and it’s now easy to hypothesize that Armitage’s performances in anything that has reached a broad audience across the Commonwealth and beyond may be more persistent than a definitive performance on the stage which most of his audience will never get to see.

If a work can’t transcend time and space, what about a performance? This seems to be one of the lines pursued in some argumentation; people want Mr. Armitage’s performances to thrill later generations of viewers as those of the leading men of screen and stage have done. Actually, I don’t think that Armitage’s current position as a performer puts him in a bad place to have this happen even if he never makes a major motion picture. Historically the vast majority of all performances in all media by all actors up until the second half of the twentieth century were simply been lost except in the memories of their audiences. We know their names, perhaps, and their paintings or still photographs of them, and if spectators wrote down their impressions we know what was thought of their performances. But before the 1890s they were not recorded on media; negatives of 80 percent of silent films have been lost; the shelf life before disintegration of the media used to make films in much of the latter half of the twentieth century is about fifty years and much of this material is likely to be lost as well. In no sense can we say that important things will survive, as the definition of “important” is incredibly arbitrary and defined mostly by the judgments of posterity, thus inherently retroactive; the works of some of the most popular artists of the silent film era are completely lost. If we could see all of silent film and judge those works and performances by our standards, it seems we might be likely to choose to preserve some items that are lost, and our own notions of what is artistically significant in silent film might change substantially. Mr. Armitage is actually working at an interesting period in the history of visual technology, in that computers and digital version of productions may substantially alter the patterns that determine which works of film and television are preserved or disappear. It’s not that the new media are inherently eternal. They’re not, although some of them may be slightly more stable under normal atmospheric conditions than acetate film was. (A bigger issue is the machines that play them, which have a tendency to break down easily and change rather quickly these days.) I think what’s decisive, though, is that these media are potentially much more widely distributed and the segment audiences that preserve a particular work and pass it on, moving it from new medium to medium because it is important to them, are substantially more numerous than they were only a decade ago. The survival of Spooks is now not contingent on the potentially sloppy administration of a particular media archive somewhere; millions of legal and illegal copies of it are located all over the world. It’s hard to imagine that its transmission to posterity could be damaged in the way that the legacy of Doctor Who has been, and it’s now easy to hypothesize that Armitage’s performances in anything that has reached a broad audience across the Commonwealth and beyond may be more persistent than a definitive performance on the stage which most of his audience will never get to see.

So you can see, I’m not especially sympathetic to the argument that there exists an independently transcendent art that Armitage can participate in, that we can know ahead of time which of his roles will be artistically significant, that his career or even his acting skills can be evaluated according to those guidelines, or that his future reputation as actor will only survive if he takes on “more important” roles. Good historical arguments can be found to question all of these conclusions. If I’m not sympathetic at all to the position that he should be taking roles in “more significant” projects, though, I am slightly more willing to entertain another argument that I read frequently–that viewers want him to take a role with more complexity, one that he can really “sink his teeth into.” One assumes, then, that Heinz Krüger is seen by those who protest it as a not very complex role, even if it is likely to be seen by a more substantial audience than (potentially) Robin Hood. And it’s at least potentially — remember, I have never interviewed the man — close to how he sees the problem when he states that he’s looking for another North & South because it was the first work in which he felt that he experimented and took risks as an artist. (He also states there that he enjoys playing villains, and it seems that Heinz Krüger would qualify for that.) It’s just he’s the only who can know what constitutes an artistic risk for him, and apart from that, complexity is quite hard to define. What, after all, is the difference between North & South (of which we approve, apparently) and Strike Back, about which we are inclined to be doubtful? (We haven’t seen Captain America yet, after all, and from the very little I’ve read about it, it is above all a brief role.)

I have no incredible interest in defending Strike Back, frankly; as a dramatic work, it moved me deeply in ways that I am still trying to figure out, but I would be the first to acknowledge that there were real problems in it and plenty of script problems. (Perhaps I’ll get to write about these more once Spooks 9 stops airing.) As a work of complexity, however, North & South is a frighteningly shaky nail to hang our hats on. The entire point of the work is the depiction of the resolution of repeated pairs of binaries that are presented mostly via stereotype: north & south, London and Manchester, town and country, rich and poor, young and old, traditional social arrangements vs. emerging manufacturing society, management vs. labor, gentry vs. wage earners, estate society vs. capitalist class society, and so on. The narrative works by means of contrasting opposites either to offer moralistic judgments (Bessie and Margaret vs. Edith and Fanny; Mrs. Thornton vs. Mrs. Hale; Mr. Thornton vs. Henry Lennox as potential lover; Mr. Thornton vs. Frederick as brother, etc.) or, alternately, to move the viewer toward the conclusion that these contradicting forces can be resolved: the woman from the lower gentry can overcome her prejudices and love the manufacturer; in the new world of the 1850s, the manufacturer, measured by his moral fibre rather than his social status, is good enough to marry the woman from the lower gentry. (Actually, it wasn’t quite that simple in England, even by the 1850s.) The screenplay added a bit of complexity over against the original work in that it gave Mr. Thornton a clearer tragic flaw and made Higgins into a more historically credible character, but really, complexity? Narrative complexity? Nah. It’s a classic tearjerker with five deaths or implied deaths of characters we have grown to care about in the last two hours of the show, and it would have been clear even to readers of the 1850s how the story was going to end. Moral complexity? Moreso in the film than in the book, but there are no real villains in this story except maybe the voracious cotton machinery. We don’t like Thornton when he brings in the Irish to break the strike, but by that point we at least understand him. Even at his worse, he’s not much of a villain, and he’s much more of a villain in the film than in the book. If North & South is complex, it’s because we are attributing that to it — not because it is inherently so. Thornton was a great role for Mr. Armitage — but mainly, I think, because of the stuff he added to it (and presumably because of how he was directed). In the hands of a lesser actor, one who felt he had to signal his emotional status more explicitly, it would have been a much lesser role, and one suspects that given the way the script was written, giving us only Margaret’s perspective and not Thornton’s (in contrast to the book), the scriptwriters were actually attempting to appeal to a female audience and willing to reduce Thornton to a (relative) cipher. Armitage, on some level, really stole the show, even if he won’t admit it.

I have no incredible interest in defending Strike Back, frankly; as a dramatic work, it moved me deeply in ways that I am still trying to figure out, but I would be the first to acknowledge that there were real problems in it and plenty of script problems. (Perhaps I’ll get to write about these more once Spooks 9 stops airing.) As a work of complexity, however, North & South is a frighteningly shaky nail to hang our hats on. The entire point of the work is the depiction of the resolution of repeated pairs of binaries that are presented mostly via stereotype: north & south, London and Manchester, town and country, rich and poor, young and old, traditional social arrangements vs. emerging manufacturing society, management vs. labor, gentry vs. wage earners, estate society vs. capitalist class society, and so on. The narrative works by means of contrasting opposites either to offer moralistic judgments (Bessie and Margaret vs. Edith and Fanny; Mrs. Thornton vs. Mrs. Hale; Mr. Thornton vs. Henry Lennox as potential lover; Mr. Thornton vs. Frederick as brother, etc.) or, alternately, to move the viewer toward the conclusion that these contradicting forces can be resolved: the woman from the lower gentry can overcome her prejudices and love the manufacturer; in the new world of the 1850s, the manufacturer, measured by his moral fibre rather than his social status, is good enough to marry the woman from the lower gentry. (Actually, it wasn’t quite that simple in England, even by the 1850s.) The screenplay added a bit of complexity over against the original work in that it gave Mr. Thornton a clearer tragic flaw and made Higgins into a more historically credible character, but really, complexity? Narrative complexity? Nah. It’s a classic tearjerker with five deaths or implied deaths of characters we have grown to care about in the last two hours of the show, and it would have been clear even to readers of the 1850s how the story was going to end. Moral complexity? Moreso in the film than in the book, but there are no real villains in this story except maybe the voracious cotton machinery. We don’t like Thornton when he brings in the Irish to break the strike, but by that point we at least understand him. Even at his worse, he’s not much of a villain, and he’s much more of a villain in the film than in the book. If North & South is complex, it’s because we are attributing that to it — not because it is inherently so. Thornton was a great role for Mr. Armitage — but mainly, I think, because of the stuff he added to it (and presumably because of how he was directed). In the hands of a lesser actor, one who felt he had to signal his emotional status more explicitly, it would have been a much lesser role, and one suspects that given the way the script was written, giving us only Margaret’s perspective and not Thornton’s (in contrast to the book), the scriptwriters were actually attempting to appeal to a female audience and willing to reduce Thornton to a (relative) cipher. Armitage, on some level, really stole the show, even if he won’t admit it.

Strike Back really does offers some complexity, even if it appears to have been designed to attract male viewers and thus often appears to retreat behind the guns and special effects. (One can’t help but think that attracting more male viewers might even have been a reason Armitage considered in deciding to accept the role of John Porter.) You have the brutal soldier who spares the life of a child, but not for any reason he can really articulate, as he’s apparently neglecting his own family at the same time and loves his daughter mostly from far away. You have the contradictions of a man who has a sort of relational ADHD. He’s fine when dealing with some pragmatic issue on the ground or some abstract problem but not with ongoing personal issues in his own space; he can rouse himself to go and save Katie Dartmouth or rescue children held as hostages by refugee traffickers, but can’t get himself together to save his own marriage. Then there’s the officer who ruins Porter’s career to save his own, who can’t seem to decide whether he should rehabilitate Porter or have him killed by placing him directly in the line of fire. Via the sidekick of the week we encounter people who are dealing with concrete problems as they try to find ways to influence their worlds: a former suicide bomber who can’t bring himself to embrace a demand that he participate in acts of terror, a computer genius and weapons expert who’s trying to make up for his errors by supporting the creation of a new government in Central Asia under a messianic-like figure, and a former SAS man who’s set up to assassinate a head of state but really just wants to disappear into the red soil of Africa. Even Layla Thompson is scripted as a strong character capable of taking on new roles and looking at things she thinks she knows from different angles. OK, to some extent here, I’m running down North & South and talking up Strike Back, but I think you get the point. Neither of these shows is inherently more complex — it depends on what we want to see in them. And certainly the outcomes in Strike Back are more complex, in that they remain unresolved or end in failures: Porter is unable to save As’ad, or Gerry Baxter, or (to some extent) Masuku. These endings force the audience to confront the inability of reality to correspond to wish fulfillment. At best, Porter is a broken hero, and though he keeps himself alive and achieves his mission objectives occasionally, there’s no more joy in the narrative beyond that. In comparison, the narrative resolutions of North & South are like a neatly decorated Christmas present, with everyone who’s not dead happily married and the audience swooning in response to a thoroughly anachronistic kiss. And I’m not convinced (with perhaps the exception of a few moments) that Armitage’s performance in Strike Back was weaker than in North & South. He controls certain pieces of his gestural repertoire more effectively now than he did back then.

In short: most of the members of Armitage’s core audiences probably still assign more cultural capital to North & South than they do to Strike Back. That’s fine. If the truth were told, so do I, probably — after all, I spend almost all my working life teaching students about the historical significance of the Western canon in a world where every second makes that body of work seem less relevant to our contemporaries, even in the West itself. But we should at least admit that our preferences relate strongly to what we’ve been taught is important by our predecessors and our context. I’m not saying that there is no way to say that any one work or performance is better than another. But I think that judgment has to be made (as I suggested in the previous post) in context rather than in abstract or absolute terms. In particular, it has a lot to do with genre and generic convention. I would argue that both North & South and Strike Back strongly conform to the conventions of their genres. But that doesn’t make them classic, or not classic, I fear. It just makes them conventional as opposed to unconventional. Given that the classic works of drama in turn create those conventions, you have to work quite hard if you want to find any role in regular (as opposed to experimental) drama that’s strongly unconventional. And frankly, I suspect the voices that are calling for Armitage to find more complex roles are not in fact wishing he would appear in more experimental theatre. I may, of course, be wrong about this.

In short: most of the members of Armitage’s core audiences probably still assign more cultural capital to North & South than they do to Strike Back. That’s fine. If the truth were told, so do I, probably — after all, I spend almost all my working life teaching students about the historical significance of the Western canon in a world where every second makes that body of work seem less relevant to our contemporaries, even in the West itself. But we should at least admit that our preferences relate strongly to what we’ve been taught is important by our predecessors and our context. I’m not saying that there is no way to say that any one work or performance is better than another. But I think that judgment has to be made (as I suggested in the previous post) in context rather than in abstract or absolute terms. In particular, it has a lot to do with genre and generic convention. I would argue that both North & South and Strike Back strongly conform to the conventions of their genres. But that doesn’t make them classic, or not classic, I fear. It just makes them conventional as opposed to unconventional. Given that the classic works of drama in turn create those conventions, you have to work quite hard if you want to find any role in regular (as opposed to experimental) drama that’s strongly unconventional. And frankly, I suspect the voices that are calling for Armitage to find more complex roles are not in fact wishing he would appear in more experimental theatre. I may, of course, be wrong about this.

These are all interpretive reasons to be suspicious of calls for more significant or even more complex roles for Armitage, but I also think we can find a key reason in his own performances to disable this objection, and this is the simple fact that he puts a noticeable amount of work into even the shortest scenes in which he appears. This pattern was reiterated to me when I was watching Spooks 9.3. I’ve promised not to talk about the current season of Spooks outside of the protected posts for that work, but if you did read that post you know that there was just as much detail, expression, and complexity in the shortest scenes in which Lucas appeared in that episode as in the longest. No detail, no expression, no possible shading of emotion, falls beneath Mr. Armitage’s notice.

Conclusion: Armitage doesn’t seem to treat anything he does while acting lightly, or as insignificant. So why on earth should we?

***

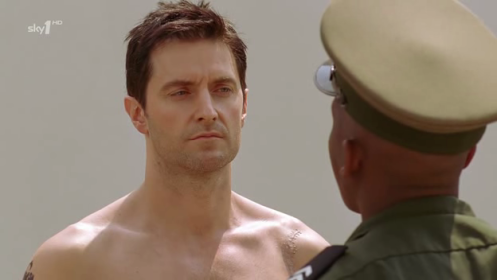

Is Armitage showing too much skin? Prison official Kingston (Jeffrey Sekele) “welcomes” John Porter (Richard Armitage) to Chikurubi Prison in Strike Back 1.3. My cap. Yeah, he’s sexy. Yeah, I want one. Yeah, I think his butt is cute. BUT: What’s important in this cap, and in the scene that surrounds it, in which Armitage disrobes completely and we see his posterior for a split second, for such a short period that if you want to cap it without blurriness you have to slomo your videoplayer? What do you really focus your attention on? Porter’s body? Or the content of the gaze that he directs at Kingston? If the latter, how does the nudity of the scene and the position of Porter’s body, particularly in comparison to the way the other prisoners are standing, undergird — or challenge — your interpretation of his gaze?

Is Armitage showing too much skin? Prison official Kingston (Jeffrey Sekele) “welcomes” John Porter (Richard Armitage) to Chikurubi Prison in Strike Back 1.3. My cap. Yeah, he’s sexy. Yeah, I want one. Yeah, I think his butt is cute. BUT: What’s important in this cap, and in the scene that surrounds it, in which Armitage disrobes completely and we see his posterior for a split second, for such a short period that if you want to cap it without blurriness you have to slomo your videoplayer? What do you really focus your attention on? Porter’s body? Or the content of the gaze that he directs at Kingston? If the latter, how does the nudity of the scene and the position of Porter’s body, particularly in comparison to the way the other prisoners are standing, undergird — or challenge — your interpretation of his gaze?

III. Beauty as Problem

A subset of the “artistic merit” problem that troubles many viewers and deserves separate treatment, as it concerns a particular subset of aesthetics, is the matter of whether Mr. Armitage’s more recent roles are too heavily incorporative of or exploitative of his physical beauty, particularly his naked body: codeword “beefcake.” (A corollary argument, perhaps: the frustration among some viewers over the exploitation of romance as a device for exploring Lucas North’s identity in Spooks 9. I still haven’t had a chance to read this post and I still want to. Done here soon. I hope.) Mr. Armitage seems to take it rather matter-of-factly, expressing relief that Lucas North’s tattoos protect him from appearing in the nude too often, noting that such shots make him more concerned about how his diet affects his appearance, sharing that he clearly doesn’t look forward to it, but never coming out and saying “I find it objectionable under all circumstances when the script forces me to do it.” (I also thought I remembered him saying in an interview that he was ok with it it in the torture scenes in Spooks 8.4 though the costumer offered him jogging pants, but I can’t find the quotation anywhere, so maybe I’m wrong.) There’s a fair amount of sympathy for the argument that a role in which Armitage disrobes in a situation where he doesn’t absolutely have to is cheap among people whose opinions I respect –including readers of this blog– and I don’t mean to suggest that it is not a reasonable position to take. I have also expressed reservations about uses of his physical charms when I wonder whether voyeurism is being encouraged in order to cover up script problems. (Although, in the scene I was critiquing in the post that link goes to, Armitage was not in fact nude. One could even say that part of the problem in that scene was that he wasn’t. The editing was extremely poor, so that we caught Armitage pulling the top sheet over Lucas’s body as Lucas rolled over onto Sarah Caulfield to respond to her caresses. Like Lucas would have thought about his modesty from the skylight view in a situation like that? That hand motion seriously compromised the credibility of the scene for me, and I noticed that fanvidders who have used that scene usually cut that half second out. That the Spooks editors didn’t manage to do it themselves views like incompetence.)

I do not, however, share that view, at least not entirely. Now, if Mr. Thornton had appeared topless, there’d have been a problem for me. But in particular, I am unconvinced by the position that disrobing either fully or partially in productions like Robin Hood, Spooks, and Strike Back offers evidence of a lack of pride or dignity on Armitage’s part, as if he were stripping for the sake of showing off, or because he has nothing else to offer his audiences, or as if his directors think there is nothing more to him than a nice chest. As his remarks suggest, he’s clearly not doing that or if he is he’s certainly equally embarrassed about it. In multiple interviews, asked about the attitudes of fans, he reiterates that he does not see himself as sexy, “a sex god,” or as a desirable object of visual lust. Now, I don’t think that as an actor, you get to disrobe wholly or partially and then make fun of fans for expressing interest or approval of what we see. But I don’t think his interviews go that far; he just repeats that he doesn’t understand the furor, and occasionally that he needs to take advantage of the opportunities it affords him while his body is still beautiful. I would be troubled if I felt like he were criticizing fans for finding him attractive after showing us his body. Though perhaps he should. Because I think this is one of the places where he may most often be misinterpreted — as if showing people your body meant you automatically wanted more from them than appreciation of your work (in a strange parallel to the women who allegedly “are asking for it” because they wear alluring clothing).

In my opinion, we’re not being flooded with nude images of him. If I remember correctly, there are two topless scenes in Robin Hood and in both of them the toplessness occurs in settings where it can be read as an indication of openness and vulnerability as well as an index of the prurience of the script or director. In Spooks we see Lucas topless in 7.1 (the MI-5 washroom — which makes sense, serves to show us the tattoos, an important character sign that we do not, however, see again in full view for this entire series, and sets an important bench mark for the question of his relationship to Harry); 7.2 (the sleepless night — men of my acquaintance often sleep topless, although we often see Lucas sleeping in a t-shirt, presumably to save Armitage the time-consuming application of transfers); 7.5 (in black and white, the waterboarding scene, though we don’t see much of his chest); 8.4 (bed scene with Sarah, torture scene, which is only a few frames, boiler-suit scene for full rear nudity, which is signaling to us something about Lucas’s relationship with Oleg Darshavin); 8.5 (bed scene with Sarah — and I would argue that we need to see Lucas in bed with Sarah to understand how manipulative their relationship is. And in bed, lovers typical disrobe). In Strike Back, his toplessness may be manipulative, but it’s also in my opinion believable in the scenes in which it appears — where Porter is having a medical checkup, disrobing during a prison inspection, digging a grave, being treated for a flesh wound, being tied up in the sun without water in hopes he’ll break (maybe I’ve missed something here) — and he’s not in fact topless in his own sex dream. Since every man with whom I’ve had sex (an admittedly small sample in perhaps both absolute and comparative terms) has had his shirt off while having intercourse with me, and many men sleep topless, I or we could reasonably conclude that he’s actually disrobing less than he might if he or his director simply wished to show off his body.

In my opinion, we’re not being flooded with nude images of him. If I remember correctly, there are two topless scenes in Robin Hood and in both of them the toplessness occurs in settings where it can be read as an indication of openness and vulnerability as well as an index of the prurience of the script or director. In Spooks we see Lucas topless in 7.1 (the MI-5 washroom — which makes sense, serves to show us the tattoos, an important character sign that we do not, however, see again in full view for this entire series, and sets an important bench mark for the question of his relationship to Harry); 7.2 (the sleepless night — men of my acquaintance often sleep topless, although we often see Lucas sleeping in a t-shirt, presumably to save Armitage the time-consuming application of transfers); 7.5 (in black and white, the waterboarding scene, though we don’t see much of his chest); 8.4 (bed scene with Sarah, torture scene, which is only a few frames, boiler-suit scene for full rear nudity, which is signaling to us something about Lucas’s relationship with Oleg Darshavin); 8.5 (bed scene with Sarah — and I would argue that we need to see Lucas in bed with Sarah to understand how manipulative their relationship is. And in bed, lovers typical disrobe). In Strike Back, his toplessness may be manipulative, but it’s also in my opinion believable in the scenes in which it appears — where Porter is having a medical checkup, disrobing during a prison inspection, digging a grave, being treated for a flesh wound, being tied up in the sun without water in hopes he’ll break (maybe I’ve missed something here) — and he’s not in fact topless in his own sex dream. Since every man with whom I’ve had sex (an admittedly small sample in perhaps both absolute and comparative terms) has had his shirt off while having intercourse with me, and many men sleep topless, I or we could reasonably conclude that he’s actually disrobing less than he might if he or his director simply wished to show off his body.

And it’s not like all Armitage does when he makes his character naked or topless is preen. He’s still acting, he still has a lot to offer. If he were stripping in order to distract from a lack of talent, that would be one thing, but I don’t think anyone thinks that’s what’s going on here. For one thing, I don’t think his beauty is conventional enough that it would work for him without acting. The question, too, is how distracting it really is — distraction is always distraction for someone. The conventions of British TV drama may trouble U.S. viewers in particular, but clearly there are people who are capable of not being sidelined by his nudity in their appreciation of his acting. I personally don’t need to see him naked in particular settings to find him plausible, but I grew up in the U.S. with its particular culture about nudity and sex on TV screens (I seem to remember it being a big deal that Ma and Pa Ingalls were shown sleeping in the same bed in the TV version of Little House on the Prairie, but maybe I am getting that wrong). I would find it odd if these productions were to conceal him intentionally in places where he would plausibly be nude — a little like the post-Renaissance practice of adding fig leaves to art that offended later, more sedate sensibilities. I’m glad, indeed grateful, to live in an age where I am free as a woman to appreciate male beauty in all its forms and to decide in particular which forms please me most. (Of course, that also gives me responsibilities to interpret wisely. More below.)

So I honestly don’t think that it’s fair to critique Mr. Armitage’s role choices on the basis that he occasionally appears topless on screen because of them (and seldom, in rear shot, fully nude — I don’t think there are further instances of total nudity beyond Between the Sheets, which would have to be treated separately in that it’s a drama about sex, and also was a very early career role). I am aware of the Armitageworld dogma that we’re supposed to say that while he is physically beautiful, what we really admire is his acting, and it’s been useful to me to be reminded of that in phases of blogging where I’ve perhaps been unduly focused on the visual as opposed to the spiritual. (It’s also just easier to write about how he looks–doesn’t require quite so much thought or hyperlinking or replaying of videoclips.) But to some extent the dogma operates on a false distinction between physicality, which is attractive but not truly artistic, indeed ephemeral, and true artistry, to which the body is irrelevant and in which the spirit is all. In short, this mantra tries to enforce a notion that Armitage’s body is somehow irrelevant to his acting. That’s just not credible. He does, in fact, act with his body — and this is true even in settings where we can’t see him using it, as in radio plays. It’s not that I think he’s acting out all the stuff he does in audiobooks by moving around in the studio. But even so, it’s his control of and use of his body that makes all of his artistry possible and perceptible in the first pace. In particular, I find it odd to have read repeated arguments for Armitage’s acting being the primary reason for the quality of North & South (as opposed to his physical beauty: to paraphrase, “we’re not watching it because he’s sexy, but because he’s such a great actor”), but then to hear that in roles where his physical beauty is more important, that he’s betraying his talent (“he’s relying too much on looking good”). Either he’s a good actor or he isn’t, and if he isn’t, it’s because he’s not acting effectively, not because he’s naked. He doesn’t stop being a good actor — or one worthy of “better” roles — because he’s topless. Or because, even when he’s wearing clothes, he’s too beautiful.

So I honestly don’t think that it’s fair to critique Mr. Armitage’s role choices on the basis that he occasionally appears topless on screen because of them (and seldom, in rear shot, fully nude — I don’t think there are further instances of total nudity beyond Between the Sheets, which would have to be treated separately in that it’s a drama about sex, and also was a very early career role). I am aware of the Armitageworld dogma that we’re supposed to say that while he is physically beautiful, what we really admire is his acting, and it’s been useful to me to be reminded of that in phases of blogging where I’ve perhaps been unduly focused on the visual as opposed to the spiritual. (It’s also just easier to write about how he looks–doesn’t require quite so much thought or hyperlinking or replaying of videoclips.) But to some extent the dogma operates on a false distinction between physicality, which is attractive but not truly artistic, indeed ephemeral, and true artistry, to which the body is irrelevant and in which the spirit is all. In short, this mantra tries to enforce a notion that Armitage’s body is somehow irrelevant to his acting. That’s just not credible. He does, in fact, act with his body — and this is true even in settings where we can’t see him using it, as in radio plays. It’s not that I think he’s acting out all the stuff he does in audiobooks by moving around in the studio. But even so, it’s his control of and use of his body that makes all of his artistry possible and perceptible in the first pace. In particular, I find it odd to have read repeated arguments for Armitage’s acting being the primary reason for the quality of North & South (as opposed to his physical beauty: to paraphrase, “we’re not watching it because he’s sexy, but because he’s such a great actor”), but then to hear that in roles where his physical beauty is more important, that he’s betraying his talent (“he’s relying too much on looking good”). Either he’s a good actor or he isn’t, and if he isn’t, it’s because he’s not acting effectively, not because he’s naked. He doesn’t stop being a good actor — or one worthy of “better” roles — because he’s topless. Or because, even when he’s wearing clothes, he’s too beautiful.

I, too, as I have said repeatedly, have felt manipulated or at least appealed to on a lower level than I really appreciate in drama in some scenes where he was topless. This is particularly true in Strike Back 1.6, I think. But when I review the list of them, I am forced to conclude that that perception says a lot more about my prejudices and the particular erotic triggers that I (and perhaps many of my readers) have than it does about his dramatic choices. It’s true that scenes of his naked body are proportionally overrepresented in fanvids and in the screencaps that we see profiled regularly, but that’s a fan choice — both of the people who edit that material together to distill it and make it more intense, and those of us who look at it. Armitage does not control how we feel about him or react to his acting decisions. It’s not Mr. Armitage’s, or Lucas’s, or Guy’s, or Porter’s, body that is inherently sexy. It’s me–and the entire group of experiences and perceptions that shape the context(s) in which I experience something as erotic–finding it that way. When Lucas takes off his clothes and puts on that boiler suit in Spooks 8.4, that scene is sad and frightening. It is not meant by either the actor, the script, or the director to titillate or to arouse anything in us but sympathy for Lucas and dread about what might happen next.

To conclude this section: I submit that we should not be asking ourselves what it says about Armitage and his career trajectory that we see him nude in roles in which it is in fact plausible for him to be topless or nude. Rather, we should ask what it says about us.

***

Lucas North (Richard Armitage) in Spooks 9.2. Per my spoilers policy I won’t say anything about this, just remark that the pointiness of his ears here have caused some of us to doubt in jest that he is completely human, and note that the structure of his ears seem to emphasize qualities in his face that make it easy for many of to imagine him playing an an elf, vampire, or other non-human.

Lucas North (Richard Armitage) in Spooks 9.2. Per my spoilers policy I won’t say anything about this, just remark that the pointiness of his ears here have caused some of us to doubt in jest that he is completely human, and note that the structure of his ears seem to emphasize qualities in his face that make it easy for many of to imagine him playing an an elf, vampire, or other non-human.

IV: A hypothetical test case

Since I haven’t yet seen every project Mr. Armitage will participate in, I can’t guarantee that I have predicted my attitude with 100 percent certainty, and in looking back over the blog I can see how my opinions are changing on things about which I thought I had a rock-solid stance when I originally posted them. I can’t draw a clear line around my preferences, or find a way to universalize them as a principle in a way that I find satisfying. For instance, I can see if he started making p*rn — by which I mean projects that had as their only visible purpose or outcome the arousal of erotic lust in the viewer — I would probably criticize that choice, and potentially stop watching him. But that’s a “know it when I see it” kind of thing, and as with so many things cultural boundaries on these matters differ. Now that I am watching more UK TV I am in fact getting more used to seeing men’s rear ends on the small screen. I assume that if Mr. Armitage were playing roles in projects filmed in the U.S. or sold to the U.S. commercial networks, we would never see him naked below the waist. I also think there’s a difference between gratuitous nudity in a project that has other merits and a project that only seeks to arouse. I think that some viewers see Between the Sheets as p*rn, for instance, but I don’t. I have my problems with that production, like probably every viewer, but I don’t think that the chief one is the fact that we see people naked or almost naked miming sexual intercourse. It has bigger artistic problems than that.

In terms of a more realistic possibility (since it’s hard to imagine Mr. Armitage as he has described himself to us up until now) making sex films: I could be wrong about all of this argumentation and it may in fact be the case that my tastes are simply different in some ways from those of Mr. Armitage’s original audiences; less educated, less refined, less discerning. The best test case for me of my claims above, should it ever emerge, would be his appearance in a genre where I find the generic conventions so aesthetically distasteful that I really can’t stand to watch it: horror films, or their close corollary in my mind, vampire flicks (though I did force myself to watch the second Tw*light film under the rubric of “staying familiar with the popular culture experiences of my students”). This might be worth more discussion as I notice that Andrew Lincoln will be appearing shortly in an AMC TV series in which he has to fight zombies. (My first reaction when I read this was that maybe Mr. Lincoln is also suffering under the lack of drama scripts in Britain that Armitage described.) I lack the necessary experience (I wasn’t allowed to see horror films as a child) and the necessary appreciation of fear or its simulation (I never liked ghost stories, either). If he were to appear in horror, I’d like to think I’d try to watch the first one he did. But my dislike of the genre might stop me from doing that, as might sub-generic issues (gore, for example, turns me off completely — but then I can tolerate the violence of Strike Back, which is in a certain sense a contradiction, I suppose). But I still think that there are potentially significant horror films that could have great roles in them: I was educated to appreciate The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, for example, and can watch that now without cringing. The Birds scares the heck out of me, but I can understand at least notionally its artistic merits. Rejecting a vampire or zombie flick out of hand would also challenge me, in that I can think of plenty of films with non-existent beings in them that I’ve enjoyed greatly, like the Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings films. If he appeared in a later series of Game of Thrones, as has been speculated and in various fora, for example, I’d watch with eagerness. I loved the books in that series that I’ve read so far.

***

Map used by Guy of Gisborne in Robin Hood 3.5. This machine-stitched receiving blanket unfortunately bears little to no resemblance to maps actually created in medieval England, which were similarly not intended for use in locating geographical features. It’s only in the last approximately five and half centuries that maps as a tool for navigation became a central concern in the West. Source: Robin Hood 2006

Map used by Guy of Gisborne in Robin Hood 3.5. This machine-stitched receiving blanket unfortunately bears little to no resemblance to maps actually created in medieval England, which were similarly not intended for use in locating geographical features. It’s only in the last approximately five and half centuries that maps as a tool for navigation became a central concern in the West. Source: Robin Hood 2006

V: Quo vadis, Armitage?

Yeah, so I guess you figured out by now that I’m not going to criticize him for taking roles that surprise me. I read him as being someone for whom the possibility of acting as a way of being is of central importance and thus as someone who will continue to take roles for reasons that are only clear to him and not to me; as someone for whom working and role choice verge on issues of identity that it would be presumptuous of me as a fan to criticize; I am skeptical about the existence or centrality of taking on important roles; I am not especially troubled by the nudity in his current roles (only my reaction to it); and if a test case comes up to change all that, I’ll look it in the face.

I’d hope, in any case, that Mr. Armitage continues to have the opportunity to make professional choices that he finds attractive and that he still has the desire to keep acting (alongside directing, if that’s his goal as well). If I had to predict what we’ll actually see from him in the next few years, I wouldn’t predict specific roles or even specific genres. Instead, I’d hypothesize that within his capacity to choose roles, he will select what he actually does based on a group of specific attitudes that he’s shown again and again:

- an interest in taking more risks in his life (wanting challenging work, wanting not to be comfortable) balanced by a certain amount of caution professionally (wanting to stay in work, and having what seems like a generally cautious response to big promises)

- a desire to avoid being “branded” or typecast as a particular kind of actor

- a desire to question whatever expectation he thinks people are placing on him most actively at the moment

In any case: I’m not going to rule out ahead of time or automatically seeing him in a particular role because it is considered by some to be beneath his talents, because it is allegedly not artistically significant, because it involves gratuitous nudity, or even necessarily because it involves a genre that I don’t care for. After my initial infatuation with North & South, I saw a lot of things in genres that I don’t typically like — I’m now watching Ultimate Force, for crying out loud!– and I respected his work in all of them. In the end, I’m watching him because I think the art resides more in the artist than in the production, more in the execution than in the content, more in the working than in the job. He’s possessed of a strong artistic gift, he works hard, and he delivers. I don’t know what more we can ask of him. Captain America and Strike Back 2: bring them on. If he stops working hard, if he doesn’t deliver — I’ll say that. But I’m not worried.

Mr. Armitage, you owe me nothing. And yet you’ve given me so much. To counter Elizaveta’s remark to Lucas: I hope not only that you are happy with what you have — I also hope you get what you want. Based on what I’ve seen so far, I’ll continue to be along for the ride. With no reservations. Indeed: with enthusiasm.

“In the end, I’m watching him because I think the art resides more in the artist than in the production, more in the execution than in the content, more in the working than in the job. He’s possessed of a strong artistic gift, he works hard, and he delivers. I don’t know what more we can ask of him.”

Your post and your conclusion sum up perfectly how I feel about Richard as an actor and the roles he plays. I keep thinking that there are certain similarities to Michael Caine, who at the age of eighty, can look back on a long career with such diverse roles. He has played the cheeky chappie, the good guys and the baddies and has brought his particular dedication to each role. He has also had a long and happy marriage to the same woman while remaining out of the limelight in his private life.

LikeLike

Thanks, MillyMe. Let’s hope Mr. Armitage can look back on as many wonderful years and diverse roles as Michael Caine can.

LikeLike

Servetus. Thank you. So very, very much. You’ve been reading my mind, haven’t you, my dear? You’ve said so many things I wanted to say.

I think I have some understanding of Richard’s need, perhaps even compulsion to act, even the feeling that there’s nothing else he can do. I’ve come to feel that way about writing. I get itchy fingers if I haven’t written in a certain space of time. I’m not writing the Great American Novel (well, not yet), I am writing for a string of small town newspapers and I am writing fan fiction that at least one person considers “trash.”

But I AM WRITING. And that is key for me. I get satisfaction from it, joy from it. I get paid for the former and hope to build my skills to be paid for my fiction one day, too.

Yes, there are other things I could do because I have done them; but writing is what I feel “called” to do at this point in my life.

Whether or not Richard was born to act (although it certainly seems that way from my perspective) he has chosen this path and oh, how beautifully and skillfully he does it.

I am glad you discussed the subject of nudity in Richard’s roles. There has been some speculation that those fans who complain most about him ‘getting his kit off’ are Americans, simply because the nudity that is acceptable on UK TV is not in general seen here on network television (I never watched NYPD Blue, but I believe they did push the envelope in that regard).

We aren’t accustomed to seeing the bare bums of TV stars who aren’t on HBO, Showtime or Stars, and perhaps that is disconcerting. But quite honestly, in my opinion, many a mountain has been made out of the molehill that is RA’s relatively small amount of bare flesh on screen.

To me, it’s always been well within the context of the scene and suitable for the character. (I do agree about the clumsiness of that bedroom scene with Sarah C.–I remembered thinking, why is he pulling up the sheet like that? I’m pretty sure he’s probably supposed to be naked here and is he covering up for the Peeping Tom sitting atop the skylight?)

I remember there being a furor over the boiler suit scene from Spooks 8. I’m with you; I did not find that scene in any way meant to be sexy or titillating. A man who was putting his life back together after 8 years in prison was once more placing himself in the hands of his former torturer as part of his job. It made my heart hurt for Lucas. RA seemed physically diminished in that scene with Oleg, as if he literally shrank into himself.

Similar scenes had been done with male leads previously in Spooks. So why was RA singled out for criticism?

(Oh, and as uncomfortable as he appears to be doing topless scenes, I suspect we never have to worry about him venturing into Sk**flicks as his career mainstay)

As to his physical beauty, I acknowledge it and happily celebrate it. Can’t understand why others don’t see it. Would I find him as compellingly stunning if I didn’t find so many other things I like about him? For me, I think not.

I’m attracted to the man, to what I know of him, inside and out.

Richard is a great actor and I will watch him in any project he chooses to do, because it’s true: the role may be small, but it won’t be insignificant to HIM. The source material may not be Shakespeare or Proust (loved how you pointed out that “classic” status may ebb and flow), but that doesn’t mean any less complex a character. Richard will always do something remarkable with it, this I firmly believe.

I’ll hush for now before I write another book. (Remember, I said I liked to write . . .)

LikeLike

Thanks for your support, and as always: write away!

I’m not guaranteeing I’ll always think this way, but I thought after awhile pondering the Captain America question that I needed to figure out where my own reactions were coming from. I’m half of the equation in “me + richard,” and indeed the only half whose decisions and reactions I can control. 🙂

I do want to say two things about the nudity: one is that I understand and respect those who don’t want to see nudity on screen. That is a valid decision to make for oneself and again we ourselves are the only people who can determine or control or reactions. But there’s a certain problem in talking about his physical beauty but then implying that it makes him less of an artist when the relationship between those two things are complex. If he looked like Steve Buschemi (who I love to death) he never would have gotten the role of Thornton, I suspect. The second is that I probably am going to continue to struggle with this myself as I find watching his beauty well nigh irresistible. Though I haven’t done much picture analysis lately (it’s been a while since I used the tag “objectification”), it will inevitably recur. But I want to make it clear that that’s about me.

LikeLike