The Genesis of Perving, ad quod Servetus respondit: ONE

Response to Judiang‘s post here, as I didn’t want to threadnap, though writing here may inadvertently have that effect. Feel free to comment in either place on this question if you’re moved to do so. The question of objectification that lies at the heart of Judiang’s post has intrigued me for some time. I’ve written about it here repeatedly in tangential ways, but this is my first post that takes on the topic directly.

[At left: Richard Armitage in Wellington, March 13, 2011. A photo that always triggers my objectifying tendencies. Servetus likes her men to smile while they are being objectified. In the original photo from which this head shot was taken, Mr. Armitage was being used to advertise the close ties between England and the Commonwealth countries in response to a crisis. Now, since I don’t care about the person with whom he was photographed, I simply use the cropped photo to make me grin.]

[At left: Richard Armitage in Wellington, March 13, 2011. A photo that always triggers my objectifying tendencies. Servetus likes her men to smile while they are being objectified. In the original photo from which this head shot was taken, Mr. Armitage was being used to advertise the close ties between England and the Commonwealth countries in response to a crisis. Now, since I don’t care about the person with whom he was photographed, I simply use the cropped photo to make me grin.]

In this post and elsewhere, I understand or define objectification as the reduction of a person to the status of a thing, which is then instrumentalized for a specific purpose. More narrowly, sexual objectification involves the reduction of a person to a thing for the purpose of sensual or sexual gratification. A few disclaimers: I am myself a major objectifier (sexual and analytical) of Richard Armitage, so hopefully nothing I write in this post will make anyone think that I’m pointing fingers at anyone beyond myself. I’ve copped to my feelings about objectifying Richard Armitage and the reasons for them, but everything about this blog has turned out to be a journey and my feelings on this topic certainly will go on that journey, as well. Also, I’m not criticizing you if you agree with Judi, or prefer a simpler discussion of these things. Nor do I think less of anyone who just looks at pictures of Richard Armitage and thinks, “beautiful!” “sexy!” “I want him!” or something salacious, and nothing beyond that. I think those things, too. Short of engaging in actual endangerment — and looking at a picture and admiring it, no matter what you think in response, does not directly harm Richard Armitage in any practical way — what you do and think as a fan is your affair.

[At right: another photo that often sends me down the road of objectification. Richard Armitage, 2007. One thing that almost always lights the flame of sexual objectification in my belly is the beginning of the crinkle in the left corner of his mouth. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com.]

[At right: another photo that often sends me down the road of objectification. Richard Armitage, 2007. One thing that almost always lights the flame of sexual objectification in my belly is the beginning of the crinkle in the left corner of his mouth. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com.]

I understand Judiang to be making the following assertions: that art is, inter alia, a means of capturing or making permanent the beauty of the human form; that art only objectifies when sexual arousal is its primary or sole objective (i.e., when it is pornographic); that photographs of beautiful living people are the practical equivalent of art that idealizes the human form; thus, if appreciating art does not constitute objectification, neither does appreciating the beauty of the living Richard Armitage, especially since many (most?) fans also discuss matters beyond his body. Judi adds an additional argument in support of her derivation of the origins of art and appreciation of the human form: that is, that even when such appreciation ends in lust (or solely in lust) on the part of the viewer, this outcome is a natural result of the instinctual imperative of the human species to reproduce. She concludes that pictures that are beautiful do not exploit as long as they are made or used in the service of appreciation of beauty. Finally, she adds, Richard Armitage is an adult with agency and has made the decision to appear near-nude, so that in any case, he is not being exploited or objectified against his own will. In the end, she terms fan protestations that Armitage is also, or more importantly, a talented individual, political correctness, which can be dropped without worry because we all really understand what’s going on when we admire Mr. Armitage’s body.

[At left: There it is again, that crinkle on the left side of his mouth. A publicity photo from 2005 or earlier. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com. Servetus thinks she got her preference for smiling men from a boyfriend who told her that he liked pornographic images of women better when they were smiling because he felt then that they were not being exploited.]

[At left: There it is again, that crinkle on the left side of his mouth. A publicity photo from 2005 or earlier. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com. Servetus thinks she got her preference for smiling men from a boyfriend who told her that he liked pornographic images of women better when they were smiling because he felt then that they were not being exploited.]

Judi and I agree on a great deal, as is probably already clear to anyone who’s read this blog for very long. Judiang says in her post that we should not be so worried about sexual objectification. I agree with the argument that hand-wringing about it is pointless, as I do with much of what she says there. For instance, I share her amusement about the apparent compulsion among many fans to insist, after the response to his beauty, that one is just as moved by his talent — although I would add that the fact that Armitage is “more than a pretty face” is a credible explanation for why we continue to watch him once we’ve become slightly more immune to the power of the pictures to flummox us. Moreover, I agree, on the whole, with the point that Armitage’s physical appearance is irretrievably part of his appeal and that his embodiment can’t be meaningfully separated from his acting talent, something I called “the Armitage morass.” I also share her opinion that Mr. Armitage’s appearance topless or nude from the rear reflects his own adult decisions (see section III of that very long post, entitled “Beauty as Problem”). And I’ve frequently compared Mr. Armitage’s physical appearance to various pieces of Italian art (like Judiang, to David, to mannerist style in which certain body elements become elongated to stress their sensuality or attractiveness, and very early on, very briefly, to Renaissance angel styles).

[At right: a Cats-era photo. Left corner of the mouth!!!]

[At right: a Cats-era photo. Left corner of the mouth!!!]

But I also find a few points of difference from Judi that may be worth considering. On the whole, I think that images inherently objectify just as any kind of representation or analysis does, that these photos we love so much objectify Mr. Armitage, and that when we ooh and aah over them, we participate in this sort of objectification. How we “should” *feel* about those processes is a separate question. On that level, I don’t disagree with Judi, or at least not much. Although I’m convinced conceptually by a lot of what feminist critics say about pornography, for reasons that have to do with my relatively strong feelings about freedom of speech issues and my fairly strong pragmatism, I’ve never been a principled opponent in practice, and I use pornography myself for the purposes for which most people use it. I can’t separate myself from the culture in which I live or pretend that I do not react to the currents all around me, that the things that drive sexual arousal and the boundaries around its acceptability for me are something I can define independently of what is on offer for everyone else. But nonetheless, I can question them, and while I don’t think there’s any point in forbidding objectification, I do think that admitting that it is occurring can lead to honest discussions over it and self-examination that are worthwhile. Maybe a world without sexual objectification is possible, and if so, I would probably like to live in it. Admittedly, I tend to be a both / and as opposed to an either / or kind of gal, and that attitude characterizes my response to this problem.

It may help to explain my position if I start to present my objections via a discussion of my disagreement with a major premise of Judi’s argument: her asserts about the natural tendency of humans to evaluate other humans sexually on the basis of our evolutionary priority to reproduce. I’m a historian, so I’m naturally going to be skeptical of any non-contextual claims about human nature; as a poststructuralist manqué, I also tend to see evolution as a discourse, a representation of reality, which is at best opaquely knowable, rather than a true statement about it. I think it’s illusory to suggest that our evaluation of reality is somehow accurate; what we “know” is always colored by what we believe, although of course at present we are encouraged not to consider this possibility. As Wesley Kort writes, “[O]ne of the regnant beliefs of our culture is not only that we operate without beliefs … but that we live without the assistance of culture, encounter reality directly, and see things as they really are.” Of course there are gradations in my perception of the epistemological status of the sciences, as there probably are in yours; I find less to criticize in the conclusions of evolutionary biologists (who describe and document how processes like reproductive advantage work) than I do in the work of evolutionary psychologists, who talk about how humans respond cognitively or emotionally or behaviorally to evolutionary forces that operate below their conscious radar. Much of the latter seems to me either crudely essentialist or simply unverifiable by any sort of scientific testing. In any case, a lot of what I object to in Judi’s post stems from my rejection of evolutionary discourse as an objective statement about reality. In what I say below, I’ll be making a fairly conventional cultural historical argument.

[At left: cover of the first issue of Playgirl, June 1973. Source: wikipedia]

[At left: cover of the first issue of Playgirl, June 1973. Source: wikipedia]

But the evolutionary point is a mere buttress of an argument that is actually made about the nature of images and art. So, one place we could start to analyze this matter in response to the way these questions are connected in Judi’s post is by asking whether looking at Richard Armitage (or pictures of Richard Armitage) and deriving aesthetic or sexual pleasure from them is the same thing as looking at particularly beautiful representations of the human form in art of previous centuries. Are the perceptions of Michelangelo’s contemporaries the same as ours, or even comparable? Is it the case that humans have always admired beautiful depictions of the human form, but that now we have come to understand that this activity is the result of natural human instincts? A historian would answer this question by saying perhaps, but the way that they have done so, the standards operating in each case, are both primarily conditioned by culture rather than by biology. The influence of cultural forces explains why notions of beauty do not carry across time and space, but always vary and operate within a particular context. It’s certainly not the case that the naturalistic representation of beauty has always been the primary or only context for determining what constitutes a beautiful representation of the human form. The influence of culture also explains why, for instance, that until my own lifetime, since the 1970s or so, it was not widely socially acceptable in the United States for women to consume images of male frontal nudity. This development (usually associated with magazines like Playgirl and Viva) was the result of targeted marketing that encouraged women to “consider their sexual appetites for men’s bodies as equivalent to those of heterosexual men for women’s bodies.” (Playgirl, which is still in production, now enjoys a significant proportion of gay male readership, but that wasn’t its initial planned audience.) I’ve been party to some fairly racy conversations about how Mr. Armitage might look if pictured frontally nude. That we have those conversations — in virtual back rooms, of course, and always in relative privacy — is at least in part a result of the fact that cultural standards have made it acceptable for us to do so. I suppose some people might argue that in consuming Playgirl, women were being allowed to admit an inherent biological desire, but even so, the form in which that formerly forbidden, now permissible, desire was to be expressed had to be culturally mediated. In short: we had to be taught to define as beautiful objects of desire — whether at rest, as at first, or erect, as the genre developed — photographic representations of the penises of gorgeous strangers.

That I myself –like many of my readers, presumably– find such pictures beautiful or arousing is undeniable, but it also testifies to my place in history. If it were the case that evolutionary instinct controlled desire, we might conclude that we would only desire those bodies that conveyed a sense of reproductive advantage. In contrast, however, culture teaches us that all kinds of bodies that might not even be reproductively viable are attractive (one thinks of the debates over anorexic-looking women who do not menstruate, women with prepubescent figures, who are presented to us by people in the fashion industry as attractive). Culture determines what can be successfully sexualized in any historical context, and this process is incorporated in the creation of art. This claim brings us to ask the question of what art as a representation of the human form actually does. That is, art is not really a naturalistic representation of the human form, although it may involve that particular style (during the Italian Renaissance, that element of art was striking, and there have been periods of realist art, for instance in the later nineteenth century, and then again with the advent of photography, that have emphasized naturalism, which we might call “the appearance of being natural”). When we look at art, we do more than judge its beauty independently based on an eternal or inflexible or evolutionary standard — in the case of naturalism, by the criterion of what appears more real, for instance — but rather, the judgment of beauty involves taking a position on the legitimacy of aesthetic standards; that is, even if biological imperatives play a role in it, it is nonetheless an inherently value-directed, value-intensive activity, one directed by cultural producers. Art and artists thus do not merely respond to human drives; rather, they are aware of these aesthetic standards and seek to move us on this basis. We appreciate art, but it also manipulates us based precisely on the standards we use to evaluate it.

That I myself –like many of my readers, presumably– find such pictures beautiful or arousing is undeniable, but it also testifies to my place in history. If it were the case that evolutionary instinct controlled desire, we might conclude that we would only desire those bodies that conveyed a sense of reproductive advantage. In contrast, however, culture teaches us that all kinds of bodies that might not even be reproductively viable are attractive (one thinks of the debates over anorexic-looking women who do not menstruate, women with prepubescent figures, who are presented to us by people in the fashion industry as attractive). Culture determines what can be successfully sexualized in any historical context, and this process is incorporated in the creation of art. This claim brings us to ask the question of what art as a representation of the human form actually does. That is, art is not really a naturalistic representation of the human form, although it may involve that particular style (during the Italian Renaissance, that element of art was striking, and there have been periods of realist art, for instance in the later nineteenth century, and then again with the advent of photography, that have emphasized naturalism, which we might call “the appearance of being natural”). When we look at art, we do more than judge its beauty independently based on an eternal or inflexible or evolutionary standard — in the case of naturalism, by the criterion of what appears more real, for instance — but rather, the judgment of beauty involves taking a position on the legitimacy of aesthetic standards; that is, even if biological imperatives play a role in it, it is nonetheless an inherently value-directed, value-intensive activity, one directed by cultural producers. Art and artists thus do not merely respond to human drives; rather, they are aware of these aesthetic standards and seek to move us on this basis. We appreciate art, but it also manipulates us based precisely on the standards we use to evaluate it.

[At left: Claire Newman Williams photo of Richard Armitage (2009). Thought by many observers to have been altered to suppress eye and laugh lines. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com.]

[At left: Claire Newman Williams photo of Richard Armitage (2009). Thought by many observers to have been altered to suppress eye and laugh lines. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com.]

I discussed this dynamic a bit in the post I made on the photo that Judiang posted (and of which I didn’t ever finish writing the second part. Oh well, I can always hope), and diagrammed the ways in which the shading of the photo directs the eyes toward particular elements of the photo and away from others. The photo is reproduced here above right. This problem is accelerated in capitalism, which seeks not simply to satisfy the desires of consumers, but even more to give rise to desires in us that we didn’t perceive before. It appears particularly acute in the current day, considering all the controversy over photoshopping of images of women in order to enhance their attractiveness. I’m sure everyone remembers the Dove evolution commercial — which unmasked the artificiality of the beauty industry as seen through advertising, even as it undermined the ethical impact of its own argument by trying to sell us a beauty product. Even if the image of Lucas and Maya weren’t shopped at all, Mr. Armitage is still made up and (un)costumed for a particular role in a way that attempts to provoke our interest based on a particular canon of aesthetic values. Moreover, some images of him are clearly photoshopped; it would frankly be odd if they weren’t.

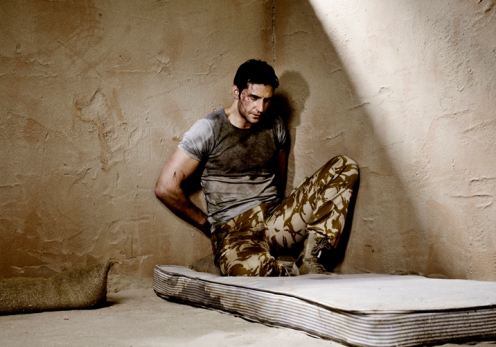

Richard Armitage as John Porter in a promo photo related to Strike Back viral video by David Clerihew. Source: Русскоязычный Cайт Pичардa Армитиджa; I got it from Richard Armitage Net.

Richard Armitage as John Porter in a promo photo related to Strike Back viral video by David Clerihew. Source: Русскоязычный Cайт Pичардa Армитиджa; I got it from Richard Armitage Net.

My point here is that we’re not really admiring Richard Armitage when we admire a picture of him, or at least not only him. We’re admiring a work of art that has been manipulated to meet the aesthetic standards of our own period, standards that we are taught by our culture and that we pass on and develop participate by participating in. For some ethically troubled readers, that status of an image could potentially serve as a relief — if we’re not objectifying a person, but rather an image, there’s no damage to the person, right? On this view, if the person who allows the image to be made of him consents, that frees us in a certain sense. In contrast to some of the roles he’s played, Armitage is not a prisoner; we are not perving on (to use Judi’s phrase) torture or coercion. On the other hand, it’s clearly the case that the image engages in an objectification of the person pictured based on the aesthetic standards of the person who created it and in line with what s/he thinks viewers of the image will like to consume. By viewing images of Armitage we clearly participate in processes of sexual objectification that are carried out for our benefit by people who wish to sell us something — people who both assume we want to consume what they have on offer and seek to shape our desire to consume further such products. What CP said in response to pictures of bound John Porter that surfaced in April, one of which I reposted above, puts it particularly well:

the actor is an accomplice to this scenario. In order for this photograph to exist, someone tied his wrists behind his back and told him to get on his knees, and he willingly complied. No matter how believable Porter’s distress, still I know this. What I’m seeing, then – the strain of taut muscles, the heaving chest, the desperate eyes – is being performed for me, and I too am an accomplice.

Yes, the actor consents to his objectification in this scenario. But, as CP points out, he consents at least in part because we have already indicated (or have been assumed to indicate) that we, too, consent to the objectification and indeed approve of it.

I’m not saying that it’s wrong to appreciate Mr. Armitage’s own particularly fine human form, but I do think we also have to acknowledge that we think it is fine because of the cultural atmosphere in which we live. Moreover, we need to understand is being sold to us as well — not on the basis of responding to our reproductive desires or evolutionary priorities, but at the behest of an industry that exists to sell us images of men for our pleasure and to profit from this activity. This industry then seeks to convince us that we need ever more images like this one, better ones, with ever higher resolution and even more perfect skin. That this industry tells us that our desires are natural (or come from our evolutionary “hard-wiring,” a metaphor that always bothers me when I read it, since human synapses are only deceptively similar to physical electric circuits, and while they have “natural” components, they also are heavily influenced themselves by matters such as habit or habituation) is also part of their marketing technique.

Richard Armitage, photo extracted from a tv magazine cover, Fall 2010, by Heathra. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com. Even here, there’s still a bit of that left corner oral crinkle.

Richard Armitage, photo extracted from a tv magazine cover, Fall 2010, by Heathra. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com. Even here, there’s still a bit of that left corner oral crinkle.

In short: I don’t think we can say that images of Armitage are not exploitative. They are certainly exploitative; they are certainly objectifying in the most basic sense of instrumentalization. (For a philosopher’s definition of objectification look for yourself here: I think that many of us, including me, objectify Armitage in at least two senses of this definition.) Every time I have a frustrating encounter with a colleague and flip over to a screen with a beautiful photo of Mr. Armitage, one that calms me down or sends a jolt of dopamine through my system, I’m instrumentalizing him. I make him a thing to give me joy. Every time I watch the train scene to imagine that I’m the one being kissed, I’m objectifying. Images of him are tools for my pleasure. That fans also discuss Mr. Armitage’s considerable dramatic talent does not mitigate the objectifying function or status of images of him. No one who puts an unbelievably beautiful picture of his face and eyes on the front of a television magazine is hoping to sell most readers the magazine on the basis of the acting talent of the artist pictorialized. They want to sell that arresting glance and the synecdoche that it implies in the mind of any viewer who knows who he is and some who may not yet do so. Moreover, even if I were willing to claim that images of Armitage did not cause me to objectify him, that would not mean that others were not doing so on the basis of those images and perhaps justifying it as “natural.” I think it’s fine to say we like to look at him because images of him are beautiful and desirable, or because they make us feel good, or even because we find them arousing. I do not even necessarily claim we should stop — any such claim would probably be pointless. We just should not deny that we are also objectifying him when we do so, or imply that we are not active accomplices to the processes I’ve described above, or that this activity takes place because inter alia we are also being sold an argument about how doing so is natural, so we don’t have to feel guilty about it or even consider it worth being aware of. And that we buy this argument: with our minds, with our eyes, and, most decisively, with our credit cards.

***

Next piece: on what art does, with especial attention to the Renaissance.

There is a great deal to ponder in this post – as usual! 🙂 Just as an initial reaction, I see more of a semantic difference in the views of judiang and servetus – but words are crucial, too, to explain the subtle differences of approach. “Perving” carries slightly more emotional weight than does “objectification”. On the one hand, I would see objectification as the beginning of a process. In itself, it might be like the proverbial Chinese food – hungry again, in this case perhaps for something more. Thus we seek to find a satisfactory reason for the initial reaction to a person. Something which makes us feel intellectually justified in “perving”. As for perving, if we cease to perve over the physical aspects of a crush on either someone we know somewhat in real life, or someone with whom we’re in a romantic relationship, or a public person, then something has gone from the sexual aspect. Stopping here, as there are too many parts to the post, to put the whole together yet…

LikeLike

I tried to make it clear that I’m not opposed to anyone having a sexual response to seeing pictures of Richard Armitage. That would be hypocritical as well as pointless. We live in a world where objectification is a standard practice. 🙂 I just am troubled by claims that doing so does not involve an objectification of Armitage. In particular, I started to think as I started writing this, the conventions of objectification are not value-free and we shouldn’t kid ourselves about that (even as we objectify happily).

LikeLike

Well, Servetus,

A most thought provoking post. My graduate student brain stuck on the various terms you used–such as epistemology in terms of what we know and how we know it.

To turn that term 90 degrees on its head to focus on me, I would say “what” I know is that Richard Armitage is the whole package–looks, talent, and a voice to die for. And “how” do I know this? Because I’m an unabashed puddle of jelly as I giggle with my friends about our lust for him. And, it’s nice to know that I’m not alone in my fascination with him. Besides, it is what it is and I just go with the flow. He is my non-guilty pleasure.

Hey, he’s more handsome and charming than any “man” has a right to be, so he must be a god(little g), right? At least he is in my world. And the fact that he seems

so wonderfully nice and couretous and gentlemanly in interviews is icing on the cake. We ladies like our bad boys, but we also like our bad boys spiffed up and polished.

Cheers! Grati ;->

LikeLike

Grati, I agree! Knowing I’m not the only one (and at my age too!) to have such a fascination for this wonderful man, and to be able to share with this group, makes me feel really good inside. 🙂

LikeLike

I’m not trying to suggest, with this post or the ones that follow it, that anyone should or should not react in any particular way. in particular i do not want to suggest that people should feel guilty. However, i think we should have the courage to call it what it is.

LikeLike

Right off I plead mea culpa for using the evolutionary argument. I’m usually annoyed when people resort to our racial beginnings to justify their arguments, (the latest vogue being covert racism) and there I was, resorting to the argument also. In lame defense, I’ll say my post arguments began in earnest and I should have stopped while I was ahead.

That being said, while it’s true that our objectification of each other comes value added by society and the times, there is at our cores a desire to look at each other, whether sexually or otherwise. Even in societies where that is frowned upon, the desire is even more so, i.e., just the turn of an ankle is highly erotic. I don’t think this is something totally made up by The Biz and sold to us. There is something there, underneath. I realize this is all supposition on my part and I’m not inclined to find studies in support. Our debate is mostly conjectural anyway.

Technically, yes, we all objectify; I don’t deny that. But we technically are a lot of things but there is usually a line by which we decide whether something is really one thing or another. So while we technically objectify RA, I don’t believe we are objectifying in the negative way being criticized in some groups today. What we do is essentially harmless.

That is why I disagree we are being exploitative. Personally, I think the adult object of the purported exploitation is the one who gets to define the situation. I can only assume that RA was free whether or not to take those roles and did not feel exploited when he did them. What other people decide to do with RA’s material is strictly their business. Did he know those images would be used to sell his work? Of course. And selling those images is the what keep him in business. It’s the nature of the beast. If he doesn’t feel exploited, then I don’t feel I’m exploiting him.

Like Fitz said, I think our differences are basically semantic. We may be quibbling over where we draw the line in defining sexual objectification; my definition isn’t as strict as yours.

I’m pleased we live in times when we can have this discussion. Forty years ago, the whole idea was still risque. Imagine, women perving on men, shame, shame, shame! 😉

LikeLike

I suspect that there are evolutionary arguments available that don’t necessarily involve race. “Race” is a historical factor — both in terms of how it enters the narrative account of human evolution (in the sense that people develop “racial characteristics” in response to their environment, according to evolutionary biology) and in the sense that race as we think about it today was not a category for Westerners before the late 17th century. If I understand what people who student DNA have to say correctly, what we call “race” is limited to a very miniscule proportion of our genes, perhaps 1% or less (see posts on the ridiculousness of the Albany plot strand in Spooks 9 on this topic).

Re, is there something that precedes culture, I agree this is conjectural. I tend to think there isn’t, but that has to do with my own experiences of developing as a sexual being.

Re, the adult object, I address this in part three. Yes and no. We are all exploited in some way as soon as we sell our labor.

I think what I’m trying to say is that for me the point isn’t whether we objectify. Of course we do. We shouldn’t let ourselves off by claiming that we’re not. If we’re going to say what we are doing is okay we have to find a further justification for it (than the ones I read in your post).

LikeLike

Again I was imprecise in my terms. (Sorry, more fuzzy thinking). I meant racial in a different way; a different word wouldn’t have been so confusing.

So do we really need further justification? Can’t wait to read part three!

LikeLike

Well, maybe not everyone does 🙂 Maybe it’s just me. 🙂

Part 2 is about Renaissance art.

LikeLike

Servetus, you’ve given me a lot to think about on first reading.

My initial immediate response was that yes, I am one of those “politically correct” fans who feels the need to quickly follow an admission of admiration for Richard Armitage’s beautiful looks and body with the fact that I also admire his talent and that he appears to be a wonderful man. But for me personally, I think the guilt about political correctness plays only a small part. My crush as a mature, middleaged woman has me looking at Richard as someone I admire as more than just an object of lust (although believe me, there’s plenty of that as well 😉 ) Am I trying to separate myself from the purely superficial fanbase? Probably.

Growing up I had crushes on cute singers and actors (David Cassidy anyone?) which were superficial at best, based entirely on what I saw on screen and in the teen mags. There was the occasional shirt-off pic, but that was it. The opportunities for “perving” just weren’t around in those days. Now, social media and the more open culture of film and television has changed all that. (None of the above is a criticism of those who admire Richard Armitage or anyone else based purely on good looks and a gorgeous body)

Because of my upbringing and age, it took me many many years to become comfortable enough to admit that I enjoy looking at and admiring a beautiful male body. Nowadays, I quite often open up my email to find a pic of a gorgeous naked man from girlfriends, we all seem to feel so much more relaxed about it. Those instances are purely gratuitous, I might add!

As an actor, Richard uses his voice and body as the tools for developing a character, and he always makes such a strong first impression. When I think of Guy of Gisborne, whom I love, I tend to think of the physical aspects of the character first: those eyes, the strong thighs encased in tight black leather, the smirk, the swagger, the rhythm in the saddle. Very quickly after, it’s his yearning for acceptance, his love for Marian, his pride and anguish which invoke all manner of feelings inside of me.

To be completely honest though, I can’t always separate the admiration of a character’s physicality from RA himself. When I look at Paul/Lucas/JP especially, I find myself also seeing the reality of Richard’s physical being. Knowing that he looks like THAT behind closed doors…*sigh* (maybe this belongs on RA confessions 🙂 )

LikeLike

I was of the Sean Cassidy generation 🙂

On the “but of course I admire his acting, too,” thing — I rushed over this too much to be able to treat it carefully, but I agree that it’s his talent that keeps you watching (and other people, too. Last night at my weekly beer date I actually got into a conversation with a man, a professor of film/media, who thinks he’s a great actor, one of the best in his generation in Britain, and he’s not looking out of lust). I actually think one way you could tell if you were “only” objectifying Richard Armitage is if you were to look at the photos regularly and feel no desire for anything else. Most people who use pornography experience an effect whereby what is initially titillating becomes less effective in spurring arousal because it becomes too familiar. That’s not what happens with most serious fans of Armitage, and I think it’s because they in fact do admire his talents. What’s funny, and here I agree with Judi, is that many of those who mention his appearance then hasten to reassure their interlocutors that they *also* admire his talent. It’s practically a speech convention in certain circles, and that’s what’s amusing.

I didn’t address the physicality argument here because I wrote a lot about it earlier (see post on “Armitage morass” linked above), but I obviously agree that the man can’t be separated from his body.

LikeLike

I don’t feel at all an urge to be politically correct about an objectification of any male who strikes a chord straight through the middle region of the body. Forty years ago, I was happily “perving” over that centre fold of Burt Reynolds in Playgirl mag. And I was both a proper young woman and a “womens libber”. It seemed no more incongrous than being a libber AND using mascara! No guilt about either the perv urge or about mascara. We are all complex “organisms” with the instincts both to react sexually and to require something beyond the pleasure of objectification to hold the interest and to inspire analysis. (Burt didn’t quite reach the status of a crush; something more interesting above the shoulders and between the ears is necessary for sustenance). Mr. A is a generation too young for me in real life and in more ways than looks, I’m no cougar with a wish for a toyboy. However, his characters attract immensely (especially Gisborne and Lucas, but also totally the opposite – Harry K). Mind you, the blogosphere helps feed the continuing fascination, with its congeniality and inclusiveness and analysis. The blogosphere is an aspect of life and within this RA community, it is a good aspect. Thank you, bloggers and commenters, and Mr. Jobs and on a different level, Mr. Armitage.

LikeLike

I’m definitely for “both / and”. I think there’s a danger that as soon as I raises this topic, readers think I’m trying to preach. I’m not. I save that for posts on “charity.”

I think if there’s a harm to perving, it’s not specifically to Richard Armitage.

LikeLike

Please behave Ladies, Mr.Armitage needs our respect!!!

I love his inteligence and acting skills,and if I lie let thunderbolt hits me…BOOOOOM……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

LikeLike

LOL! I think you made my blog point exactly Joanna. 😀

LikeLike

If I were arguing that we should respect him more, I’d have undermined my whole point 🙂 In that sense, this blog is one huge mass of disrespect 🙂

LikeLike

I’ve been thinking lately that male beauty is really a different thing from female beauty. It seems to me that in our culture men are taught to “do” and women are taught to “be.” (I know I’m not going to be too clear about all this, because I haven’t quite nailed it down in my own mind yet. But I’ll try.)

Little boys learn that to play a role, you have to engage in the activity appropriate to that role (cowboys ride horses and rope cows, firefighters fight fires, etc.) but girls are given roles that don’t have any specific activities associated with them (being a princess, for example. What do princesses do, really? A princess is something you can be, not something you can do.)

Also, it seems to me that women can engage in any activity imaginable, but they don’t stop being women. But that’s not quite true for men–if they do certain things, they can become diminished as a man. I’ve watched my father and brothers wrestle with these choices. It’s as if being a man is partly an intellectual construct, and not just a fact of biology.

All this is my long-winded way of saying that when we admire a man’s beauty, we can’t separate our estimation of his appearance from our estimation of his character–what we admire is the kind of person we believe him to be, not just the curves and planes of his face and body. I, too, am captivated by Mr. Armitage, and consider him very handsome, but I’ve got to think that it’s due in part to who I think he is, not just what he looks like. He’s good-looking, but there are lots of good-looking men out there.

So why him, and not somebody else? I think it’s that he displays character atttributes that we value. He expresses emotions and qualities that we as women strongly desire to see a man express–passion, devotion, loyalty, and appreciation for a woman. And if I’m right in thinking that a man’s style of beauty incorporates what he does and how he acts, then that’s why he’s so beautiful and fascinating.

LikeLike

Thanks for the thoughtful comment, Soralee.

Something that is still brewing in the unpublished pieces of this comment are the conventions for male nudity. I think precisely because of what you discuss (what is appropriate for men to do in order to construct their masculinity) the valences of male nudity are really different. Women are not doing exactly the same thing when they “perv” on pictures of Richard Armitage as men do when they use pornography.

I don’t disagree at all about the point of other reasons that bolster our reaction to and love of these photos. (See Armitage morass, linked above).

LikeLike

Do you think we as women perhaps are being self-congratulatory for for using his nude pics for “perving” instead of masturbatory material as many men do with pornography, so we don’t feel so “base” according to society standards? “We know how men are. We do it differently, so we’re not that bad.”

LikeLike

Something in the back of my mind while I was writing this were my experiences dating for four years a man who was a regular consumer of pornography alongside our sex life. His position was that they were separate things, and it didn’t bother me, as our sex life was more than satisfactory (though I wondered what it would have been like without both of our experiences of pornography helping to shape our preferences and practices). That’s the partner I’ve had to whom I had the strongest sexual connection, in fact, and I think the relationship lasted “too long” because the sex was “too good” and tended to obscure other problems. But as a consequence of his preferences I had a much more intense exposure to pornography directed at heterosexual males than I would have otherwise and we had a lot of conversations about it.

One thing i asked him about because it bothered me was the fact that his experience of arousal was so exposed to norming. Playboy (or whichever publication) publishes its November issue, mails it out in brown wrapper to its subscribers, it arrives, and all over the U.S. men unwrap it, flip to the centerfold, go the bedroom or bathroom or wherever, and rub themselves to orgasm. I felt alternately amused and, as you say, condescending, about this picture in my mind. “*My* arousal is not controlled by a media conglomerate,” was my position at the time, “unlike his.”

But I think that because of the fact that these images of Armitage are created by an industry that has specifically this function, we run the risk of ending up in the same position as many men find themselves. There’s a whole discourse in the fandom about how he isn’t “conventionally handsome” that attempts to counter this fear, I think. The tendency that we’re being manipulated to find certain things beautiful desirable is there, whether we’re masturbating to pictures of naked men, or simply looking at pictures of beautiful men and sighing.

It’s interesting to me that most of the comments on this post so far have focused on the moral question (objectify or not) as opposed to the social / cultural / economic one (images that are marketed as objectifiable).

LikeLike

Feminism does seem to be turning the tables on us.

I think the focus is more moral because as @Rob, it seems to be closely tied to our views on our sexuality and its expression. As I debatable stated many months ago, there is still a puritan streak running through society.

LikeLike

I think that feminism itself can’t escape the problem of the commodification of desire. Unfortunately. Or maybe fortunately. I think there are some viewers who enjoy, at least from time to time, being manipulated in this way. I never met a man who said, “I resent that somewhere there’s a group of markets trying to shape what turns me on in order to sell cars.”

I don’t question the problem of the relationship of sexuality and morality, but still, I think that we have a tendency to think of market forces as something “natural” (like evolution) and thus not question them.

LikeLike

I agree with you Saralee, I can admire a man for his body for only a glance, but the admiration will not continue if I don’t also admire the person and the mind. I feel joy when I look at RA’s physical beauty, and I don’t feel guilty about doing so, but I also can’t separate what I feel for him as an artist/actor and as a person. I have to feel some connection to the man in order for my admiration of all his qualities to continue.

Fitzg, I also remember Burt Reynolds and that Playgirl magazine. I remember my friends and I going together to buy it and then secretly looking at Burt and talking and laughing about it. But I can say even then when I was so much younger it didn’t make me subscribe to Playgirl, nor did it make me a Burt Reynolds fan.

To be honest however, there are many actors I like who I’m not attracted to. I have to be honest that I would not admire RA in the same way, would not feel the same joy when I see him, if he was not as physically beautiful as he is. But without that equally beautiful brain, I don’t think the love would continue or be the same.

Enjoying reading the discussion and everyone’s comments.

LikeLike

Fabo, I recall the Burt Reynold to-do. My mom made my dad buy a copy during his lunch break and we were on him as soon as he walked in the door. She got to look first (because I was 13), said “oh, ok” and then handed it to me. Of course I didn’t get to see what I wanted so I immediately lost interest. The most I thought at the time was he had such a cheesy smile and was a bit hairy. 😀

LikeLike

Guess I am too young for Burt Reynolds fascination?

LikeLike

Burt Reynolds has disappeared from the Hollywood headlines.

I think at the time the Playgirl Burt centerfold went beyond being interested in him, even women, of all ages, that were not attracted to him or his movies bought the magazine. Women had been fighting to not be considered as sexual objects, and here we were for the first time turning the tables and admitting we could look at men as sexual objects too.

LikeLike

I’m interested in hearing more about this historical perspective on the issue. Did the desire to objectify precede the images?

LikeLike

I think the desire was there, and acknowledging it in a centerfold was such a radical in your face idea just blew the lid off the cover, so to speak. Nearly everybody and her sister bought that issue or saw it. Remember this was the same time that Cosmopolitan magazine blatantly talked about the sexual revolution and female orgasms. I recalled being riveted by an informative article on “The Myth of Male Orgasm.”

LikeLike

What was the myth?

I have to say that if people in the community I grew up with were using pornography it was extremely well hidden. My parents bought a Playboy if someone notorious was in it — Fawn Hall is one I remember — but not otherwise.

LikeLike

I’m straining to remember, it was about 35 years ago – I think it talked about how the male orgasm wasn’t as a big deal as it was cracked up to be and went through the whole physiological response. In short, stimulate a man enough, he’ll climax. The intensity of it was about the experience, which of course we all understand now.

LikeLike

I agree with Saralee that his apparent personality intensifies his attractiveness to us, and I think that with this amount of hotness objectifying is inevitable!

So, Servetus, is this post a preparation for Yom Kippur?

גמר חתימה טובה

LikeLike

to you, too, Arfan 🙂 Tzom kal, if you’re fasting 🙂

LikeLike

Okay, I have to share this. My five year old just asked me why I am reading this post. There was a piccy on the screen and she says,” You think he’s cute.” And I respond, “It’s more than that!” Oh, the irony! 🙂

The thing that struck me is not so much whether we objectify Armitage, it is really about HOW we FEEL about it. It is almost more about how we feel about our own sexuality and OUR expression of it.

LikeLike

I think you hit the nail on the head @Rob. I think it has a lot to do how we feel about our own sexuality and its expression. Those who are uncomfortable with it, would be more included to object “perving” on any images of RA.

LikeLike

Maybe. I have two reservations:

1) I’m not entirely comfortable with the implication that fans who object to objectification are sexually insecure. While that could be a reason, there could be other reasons to reject objectification as a practice beyond one’s own experience of sexuality. Ethical ones, for instance.

2) I think we have to think of this on a spectrum in many ways (and part of what’s been problematic in this discussion so far in Armitageworld IMO stems from the tendency to be too black / white about things): some kinds of objectification be different than others — a person could e comfortable with a picture of Armitage clothed by not with a nude Armitage, AND our own opinions change. On some days I am more or less comfortable with my reactions to these photos than on others.

LikeLike

I didn’t mean to infer that people were sexually insecure. It could be surprised, confused, uncertain, shocked. For me, I am constantly surprised by my reaction to Armitage and my response to him. And there are times, when I am not totally comfortable with it.

LikeLike

yeah, I didn’t think you were saying that. I was just exploring the implication of the position.

I think desire is / can be disturbing even for those of us who feel somewhat sexually confident.

LikeLike

Children are so alert 🙂

LikeLike

I’m a little afraid to dive into this pool, in case I will drown under the obvious intelligence of all the other posters. But, here goes nothing

Am I in the minority for feeling absolutely fine with my personal objectification? I do it, I admit it, and do not question why. He’s great looking and I like to look at him. If I have a bad day, watching some work of his (particularly Strike Back, where he looked totally awesome) lifts my spirits. I accept that and move on.

My only question to myself is, why him? Many others have endlessly debated this topic and I don’t know that a definitive answer has been reached. So again, I just accept that he is the object of my objectification (there must be a better way to phrase that) and move on.

Good luck with the fasting, Serv (and others who may be observing) Undoubtedly I will be using some RA to get through the day

LikeLike

Oh, I don’t think you’re in the minority at all. Sometimes I wonder if this debate even exists because we as women since Victorian times have been taught that “nice girls” don’t have such thoughts.

LikeLike

No, at least fabo would agree with you and probably other readers who are silent.

And i’m not “not fine” with my objectification of him. I have no guilt about it at the moment. I just don’t want to be seen to be saying that because I’m fine with it, it’s not objectification. It’s still objectification. I’m still responsible for that.

LikeLike

Oh, Serv, I agree that it absolutely is objectification. And I’m certainly responsible for my personal behavior. I think what I’m trying to say is that I recognize that I am objectifying and don’t feel any guilt whatsoever about it.

LikeLike

good for you! I have no problem with that.

LikeLike

I have also been reticent to “dive in” cindy, not only for the reason you give but for the added reason of my age. As some of you may already be aware, I am quite a number of years older than Mr. A, so the questions I ask myself are not only the “why him” one, but “why NOW – at my age?” I can honestly say I have never experienced such a thing before! Like you, I’m just going to have to “accept that he is the object of my objectification” and try to find a way to move beyond the guilt which I undoubtedly feel. Not because I feel it is wrong to enjoy looking at him but probably because others will be shocked at my reactions to him at this time of life. Believe me, I am as amazed as anyone to find myself in this position!

LikeLike

But why *not* at your age? Please don’t tell me that we dry up and blow away after menopause!

LikeLike

To answer your question, judiang – I’m living proof that we don’t!!!!

LikeLike

Teuchter- Yep, me too! 🙂

I have to admit though, I do sometimes worry about how I am perceived by others when it comes to “perving”. Yesterday in the hairdresser’s chair, I was reading a mainstream gossip magazine while my colour was setting, and my attention was arrested by a picture of a nude Zac Efron – so not my type, but I looked anyway, and for more than a few seconds. However, the minute I was aware of a young lass coming to check on me, I quickly flipped the page. Absolutely instinctive, yet a day later I still ask myself “why?”. I’m certainly not answerable to a seventeen year old girl, but I suppose it’s that ingrained niggle of embarassment or whatever it is, that still occupies a corner of my brain. It’s probably also the same reason why I keep my feelings for Richard to myself.

LikeLike

See now, here’s an example of objectification that would bother me. Did Zac Efron pose for that pic, or was it a candid shot on a beach or something? To me, candids (those not taken at a public event, rather someone taking a random pic in a street or on a beach) are very invasive. I can’t say I feel guilty for reading a gossip mag full of these pics, but I do feel sympathy for the poor person who can’t run to Starbucks without having pics published on the Internet an hour later.

That said, if nude pics of RA on a beach showed up, I’d still look. I’d just feel guilty about it.

LikeLike

Cindy, I didn’t read much of the accompanying text LOL! (the pic took up nearly half the page). It appeared to be a candid shot of him “checking himself out” (the tag line) taken on a mobile phone I think, then it’s obviously gone from there. I don’t know if he was aware of the photo being taken or not, it didn’t seem posed.

I agree with you about the lack of privacy for people just going about their day to day business, but I don’t have any sympathy for those who court publicity and the paparazzi, the reality “stars” etc who are happy for any exposure they get.

Your last couple of lines made me smile, as I would be the same way.

LikeLike

Yes, my sympathy only extends so far, Mezz. While I do feel bad for RA when he goes to the theater and someone immediately posts that fact on Twitter. Do London fans then get in their cars and drive over on the off chance that they will see him? Social media has made it hard for “famous” people to have any sort of privacy and I do feel sympathy for that.

However, there certainly are those who use (or maybe abuse is a better word) social media, and in fact all media, for their own ends. For them, I feel a different sort of sympathy. As they court paparazzi and seek exposure just for the sake of exposure, don’t they know that the rest of us think they look like idiots?

LikeLike

So I can’t help but note that this comment raises another issue about the whole question of objectification, which is the extent to which certain kinds of attempts to avoid objectification simply trigger it.

LikeLike

[…] PART ONE IS HERE. […]

LikeLike

On the Genesis of Perving: ad quod respondit Servetus — TWO « Me + Richard Armitage said this on October 7, 2011 at 9:28 pm |

Oh, yes, plenty of objectifying goes on in our culture. We are always being sold something, and we all know sex sells. We are still somewhat puritanical here in the US, so it’s sort of the tug between the appeal of the forbidden fruit and feeling that we really shouldn’t have these sorts of responses.

I find the man hot, hot, hot. I like the way he looks, his voice, the way he moves and uses his physicality. There are other good-looking, sexy guys out there I also enjoy perusing. I am only human. But I don’t necessarily like, admire and enjoy them in the same way I do Mr. A. I only know he triggers something in me no other actor/celebrity has ever done. I’ve had a few crushes along the way, but nothing on the level or the duration my mad obsession with the Armitage Effect has wrought.

I think back to my beloved Sir Guy, the character that introduced me to Richard. I ultimately fell for the character for his vulnerability beneath the swagger, the depth of his unrequited love for Marian, his need to be loved and to be able to trust, his struggle to become the better man. But in the beginning, oh yes, it was all that black leather and guyliner and artfully tousled black locks that caught my eye. And we all know the folks at Tiger Aspect weren’t think of the effect on the kiddies when they cast and attired that character . . .

Gotta go! This has been fascinating, as always, to read through all the responses. It will be nice when I can more fully participate again.

LikeLike

Hope you had a great time away, Angie.

I think there’s a difference in feeling guilty about desire and in feeling guilty about the exploitation of desire. I am more troubled by the latter than by the former.

LikeLike

Finally home, finally able to get caught up a bit. It was great visiting with my sis after the cruise, but I missed everybody back here. 😀

You mentioned that about the differences in reponses re the age group into which we fall. A sort of generation gap thing.

I wonder if my relative lack of guilt over this, at age 51 with 26 happy years of marriage under my belt, is the fact I do not have children (except for the furry kind) and so I’ve never felt the need to “set a good example” for the kids? NOT that I think any of us who are posting here, no matter what their age or family status, should feel guilty over our feelings about Mr. A,, you understand.

I think Burt was a little too hairy for my tastes. And David Cassidy looked almost like a girl, as I recall, in his centerfold pic. Never was crazy for the pretty boys. 😉

LikeLike

Woke up this (Saturday) morning to all these wonderful and interesting posts, so there goes my housework!

Here in Australia Cleo was the first magazine to feature a nude centrefold in 1972. At the time I was too young to buy it myself (my mother certainly would not have and I didn’t have older sisters!) but I was aware of the furore it created.

If the opportunity to take a peek inside the magazine ever presented itself I always took it, but it was not until several years later and I was married that I bought a copy for myself. I can remember feeling embarassed at wanting to pore over the naked images. Totally forgettable though, whoever he was!

In the early eighties there was an issue of Playgirl with Pierce Brosnan, who has been a longstanding crush of mine (now usurped by RA!) on the front cover. He wasn’t the centrefold, but I so badly wanted the magazine for the interview and the accompanying pictures that I swallowed my embarassment and bought it. I made sure it was at a store where I wasn’t known, I might add!

My knowledge of the male body was limited to sex education diagrams and my

beloved husband (we were teenage sweethearts) thus my early encounters with the nude male form in the media were driven by curiosity, usually accompanied by embarassment and guilt.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that I was, and still am to a degree, a product of my sheltered upbringing and generation. I think there’ll always be that niggle of embarassment and guilt embedded in my conscience. However with time and maturity, I have come to accept who and what I am. I am finally comfortable in my own skin and can admit to finding pleasure in admiring a beautiful male, clothed or otherwise. Even my eighty year old mother has loosened up to the point where we can now share the occasional giggle over something that would have embarassed us thirty-five years ago.

Re Richard Armitage in particular (and he’s the reason for my introspection after all) others here have said it better than me. He is simply the complete package, an endless source of pleasure, and I love that he is part of my life (albeit a secret one 😉 ). He could never be just a “centrefold” to me.

LikeLike

I do think there’s a tension in the fandom between older fans whose experiences are more like yours, a cusp of people who are like me, and younger fans whose experience of these issues are more clearly guiltless as men have always been objectified for their pleasure.

LikeLike

Thank you Mezz! I can really relate to what you have written as it pretty well mirrors my experience (apart from the magazines as I would never have had the courage!) as my knowledge was almost nil until I became a nurse and later married. Now I am able to have a giggle with friends – something I wouldn’t have been able to do years ago!

I found your last paragraph particularly moving as you have put into words exactly how I feel. To my mind he has no equal! 🙂

LikeLike

Teuchter, Cleo was controversial to begin with, but by the time I got around to purchasing it, things had settled down. It was similar to Cosmopolitan, and is still published today I think. I haven’t bought it for a long, long time. As for Playgirl, there was no courage in buying it some distance from home where the shop assistant didn’t know me!! Desperation for anything Pierce Brosnan-related drove me to it. Of course, I’m more dignified now with my (much deeper) RA crush *cough*.

Thankyou, it’s lovely to have struck a chord with you with our similar life experience and feelings for Richard. 🙂 That’s what I like about being in this blog.

LikeLike

In the US men said, “I buy Playboy for the interviews.” 🙂

In the 1970s the magazine also had some great journalism in it; this should not be denied.

LikeLike

The issue of morality/guilt as related to “objectification” or pleasure in viewing an attractive body differs in various cultures. Many are far more relaxed in social attitude to this than are those with a strongly Protestant initial influence. But that’s not the whole picture: Irish Catholisicism appears to have a pronounced prudery in expression, while other predominantly Catholic cultures haven’t. Speaking VERY generally, mind you. And social mores are not static. And Protestant Scandinavia hasn’t been notably prudish. I think I just defeated my premises. Back to the drawing-board….

LikeLike

it’s hard to talk about culture because it’s so amorphous. Kudos for making the attempt!

LikeLike

[…] PART ONE IS HERE. On my attempt to disable the argument about the acceptability of ogling based on human evolution, some readers may find this book interesting — note that a few years earlier, the same author made a forceful case for disabling the argument from culture that I made in part one, so I am not presenting this as additional evidence for my case. Part one went on to make the case that vast majority of images of Richard Armitage that are available to fans objectify Armitage for the purpose of marketing. PART TWO IS HERE; its point was to use a historical example to make the case that art, no matter how beautiful, is not free from objectification, so that even if images of Armitage, a living person, can be equated with beautiful art, this comparison does not nullify the objectifications going on in either art or photos of Armitage. […]

LikeLike

On the Genesis of Perving: ad quod respondit Servetus — THREE « Me + Richard Armitage said this on October 17, 2011 at 3:24 am |

[…] have to confess that I’m starting to run out of vocabulary for expressing it. And then I had my own (still unfinished) thoughts about perving in response to Judiang last fall. Anyway, I love you, readers who think primarily about his […]

LikeLike

F3, Day Two! One voice to thrill them all, and Armitage to bind them! « Me + Richard Armitage said this on March 13, 2012 at 12:01 am |

[…] I’m not justifying what I do in terms of whether it’s “natural” or not (it may be, though I tend to think it’s cultural rather than natural). […]

LikeLike

Stripping Richard Armitage of his human dignity: A day in the life | Me + Richard Armitage said this on March 1, 2013 at 5:34 am |

[…] readers know that I’m a fairly strong opponent of the notion that it’s primarily biological qualities or &…. My position on questions like this was heavily influenced by my discovery during grad school of […]

LikeLike

Richard Armitage, gender trouble, and status expertise | Me + Richard Armitage said this on July 29, 2013 at 6:30 am |

[…] episodic fan battle over various sorts of pictures of Richard Armitage — I was thinking about this and objectification in detail in the fall of 2012, for instance — and the application of WWRD to discipline every discussion, no matter how […]

LikeLike

Liberation: This is one of those days when I am fighting the self-esteem battle hard | Me + Richard Armitage said this on February 1, 2015 at 2:47 am |