My Richard Armitage: An interpretation. An excursus on identity and personality in 2004

Here are links to Preface (explains the series); Part I (Richard Armitage’s family background, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, and early professional experiences and training); and Part II (Armitage’s career from leaving LAMDA to being cast in North & South).

This is the next piece of my chronological interpretation of what I know about Armitage, which I am drawing from a reading of available sources and based on my own perspective. In contrast: the best conventional professional biography of Mr. Armitage available is this one at Richard Armitage Online.

Given that I’m finally publishing this in the wake of the publicity blitz for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, I should probably add that this was largely written based on materials published before November 2012. Big chunks of the stuff that’s appeared in the last month remain for me to examine, and even the stuff I’ve looked at I haven’t carefully digested yet. This project is not substantially impacted insofar as I am, by this point, reading chronologically rather than comprehensively, and this piece specifically tries to address “who Richard Armitage was by 2004.”

***

VI: A personality balance sheet from the perspective of immediately after North & South

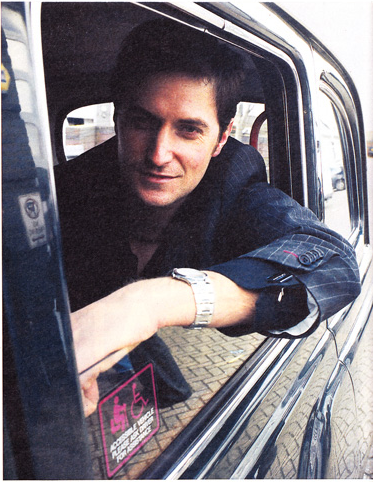

[Left: Richard Armitage as photographed by Jenny Lewis. From the first surviving North & South-related pre-publicity of 2004. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

[Left: Richard Armitage as photographed by Jenny Lewis. From the first surviving North & South-related pre-publicity of 2004. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

To pick up strands from the previous pieces of my argument: Richard Armitage came from a background that made pursuit of a performing arts career a slightly surprising choice. Moreover — keeping in mind that much of this evidence comes from Armitage’s own statements and deductions that can be made about his surroundings — his education and pursuit of his career once it started were shaped by attitudes from his background and education, especially a conservative worldview and an emphasis on industry, cooperation, modesty, manners, and doing one’s best. Finally, his sudden move into public awareness and the experience of having fans came after years of receiving practically no notice for his work beyond a few publicity interviews (indeed, no reviews at all), which likely explains important pieces of his reaction in the months afterward. I ended with the question, “Who is Richard Armitage?”

Up till this point, the would-be biographer works retrospectively to answer this question, as most of the available data was either been gathered by other researchers working after Armitage’s explosive appearance in 2004, or was stated by Armitage or his interlocutors in later publicity. From this point in his biography, however, the author is able to take up and evaluate data that appeared contemporarily to the events being examined. It’s important to note this difference in source foundation, and take a pause to evaluate what we think we know before we start adding in contemporary publicity to answer that query.

[Right: Sex symbol or “serious” actor? Initial press reaction to the broadcast of North & South, which always commented on Armitage’s sudden appeal to women and often compared Armitage’s Thornton to Colin Firth’s Darcy, relied as much on “beefcake” shots from the Cold Feet publicity as it did on headshots of Armitage as Thornton or new images. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

[Right: Sex symbol or “serious” actor? Initial press reaction to the broadcast of North & South, which always commented on Armitage’s sudden appeal to women and often compared Armitage’s Thornton to Colin Firth’s Darcy, relied as much on “beefcake” shots from the Cold Feet publicity as it did on headshots of Armitage as Thornton or new images. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

Putting aside for a few paragraphs the question about the substance of Armitage’s personality and how well it conformed to its early public appearance, it is hard to imagine that Armitage could have been much different once he emerged into public view, simply because of these things: upbringing in a national and class culture that looks negatively on self-aggrandizement and blatant expression of pride and ambition, and in which manners are still very much taken not only as the measure of a man but also as a sign of one’s social place; his parents’ background and values; a conservative mood in the family and in his raising; education in a vocational school that emphasized cooperation, manners, pushing oneself, and pursuing every opportunity; participation during adolescence in informal and formal work settings in which he was required to behave maturely; a career training that required self-restraint, a high level of discipline, and constant cooperation; and the long delay in the arrival of recognition. Unless he had been more seriously inclined to rebellion than surviving evidence suggests, with this background, he could hardly have been loud, disorderly, immodest, rude, boastful, or one of those personalities that seeks to take up large amounts of space for itself with feigned self-assurance. This is not to suggest that the young Armitage was never secretly or publicly mischievous, or even potentially immature or prankish (he referred to clowning around with a tree with unanticipated consequences while in drama school, for instance) — or that he had no ego — but the factors mentioned would have cloaked any features like these. All of the elements we are aware of in his personal history would have combined in favor of a characteristic public self-presentation for a man in his early thirties as mature, disciplined, and sober. That the public Richard Armitage would present as self-deprecating and modest, deflect praise, and refuse with humor to take himself too seriously, at least when asked to do so in public, was in that sense overdetermined, even if he at times would take the latter strategy so far that he failed to realize or refused to accept that his constant self-deprecation verged on self-undermining.

[Left: Richard Armitage as Mr. Thornton, the image that appeared most frequently in early press related to North & South, arguably a more charismatic picture than either the beefcake shots or those of the man himself. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

[Left: Richard Armitage as Mr. Thornton, the image that appeared most frequently in early press related to North & South, arguably a more charismatic picture than either the beefcake shots or those of the man himself. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

Notwithstanding this characteristic self-presentation as modest and without significant ego, key indices from his biography up to this period point equally to a personality strand we might (depending on our opinion of it) call individualist or even hedonist — a desire to work as he enjoyed and not as might be most practical or quickly remunerative, a persistent need to pursue his own desires in work as opposed to conforming to conventional vocational paths, the cultivation of physical grace and adventurousness, a willingness or even eagerness to try new things, an intellect that might be described as eclectic rather than focused, and a curiosity about the world and the people around him. In short: within the practical bounds available to him, Armitage was also someone who did what he wanted, following his own impulses, because it pleased him. Armitage’s early career steps reveal a readiness to do things because he enjoyed them or because they were interesting or provided a path to somewhere interesting, if not always a tendency to think immediately in the long term about preparation or consequences. London and the back stages of the West End might have been ideal places for a person like to this to mature, located far enough way from his parents’ home while still “at home,” all the while permitting an ease of encounter with all sorts of things he had not been exposed to before, as well as a ready-made environment full of young people like himself with similar trajectories and a useful safety valve for releasing any tension created by the discipline of work. His willingness to stay in this milieu for so long suggests independent-mindedness, tolerance for uncertainty, and enjoyment of many aspects of things as they were. While I address the question of self-motivation for success in the next paragraph, I do not read it as a factor sufficient to bring him to make life choices with undue or sudden proactivity. Armitage wanted to succeed, but not at all costs; his personality lacked a killer instinct and incorporated a tendency to seek harmony and comfort following his own definition of those terms. Indeed, Armitage maintained the luxury of pursuing his own ends on his own timetable all through his twenties — if not any level of material security much beyond the basic — by not tying himself personally to providing for a family, with the result that he had more time to pursue his interests and avoid the typical obligations on the time and pocketbook of the family man in his late twenties and early thirties. We might say that this pattern — along with his persistence in classical theater almost beyond his own capacity to tolerate a lack of larger roles on offer — suggests a seriousness even in his pursuit of personal fulfillment and enjoyment that is consistent, if not always congruent with, his values of industry and discipline. Up to the point of his entry into television, the young Richard Armitage reads to me like a person who was artistic, idealistic, and a bit unfocused except as regards his own ends and desires, sacrificing security for his own ends. At the point at which he started to go after television roles more actively, he starts to read — to me — like a person who has become somewhat more pragmatic, but only in the sense that he has begun to ask himself how he can continue to live a life with the freedoms to which he is accustomed — as if he realized that the only way to continue to pursue his desires would be to work in television, even if it was not initially his ideal setting — as a consequence of which he began to move in that direction forcefully. One can’t help but wonder if the decisive lesson he took away from his twenties and early thirties, once his career was more established, lay in the need to make sure that he pushed himself outside his personal comfort zone.

[Right: Surprised by success? Richard Armitage as photographed by Rebecca Bradbury for Vivid Magazine, in the publicity accompanying the North & South DVD release. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

[Right: Surprised by success? Richard Armitage as photographed by Rebecca Bradbury for Vivid Magazine, in the publicity accompanying the North & South DVD release. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

Armitage’s tenacity in moving in a direction once it had been decided further complicates this picture of the moral, modest, retiring, even at times perhaps painfully shy young man who has a good helping of willed interest in fulfilling his own desires. It reminds us that additional biographical data available to us point both to significant talent and ambition despite his refusal to acknowledge the former in public and the latter perhaps even to himself — if not always a capacity to capitalize upon them fully. Additionally, we see evidence of a meaningful awareness of practicality and ambition in understanding how the system of “getting ahead” in performing arts works. His early pursuit of vocational training, then speedy departure to obtain an Equity card, his return to England to work almost immediately in significant productions and as assistant to known experts suggest that he knew both how to find connections and use his talents. The line between industry, ambition, and hard work in his life story is thus not always clear; he very early wormed his way onto television sets as an extra, for instance, and managed to have at least one very minor role credited. Some pieces of his biography suggest moments of drivenness, albeit possibly a failure to able to formulate exactly what he wanted or see his way to it immediately. His recognition that musical theater would not be his ideal path came quite quickly, for instance; despite early successes, he was aware of his own dissatisfaction, as well as of the arbitrary nature of any success, and once he was artistically finished with it, while starting to audition for speaking roles, he was still able to make himself with it long enough to earn the money for his next career step (drama school).

[Left: Richard Armitage as photographed by Amit Lennon, for the Mail on Sunday, during the publicity for the North & South DVD release. My cap.]

[Left: Richard Armitage as photographed by Amit Lennon, for the Mail on Sunday, during the publicity for the North & South DVD release. My cap.]

Establishing that Armitage was not only modest, virtuous, and self-deprecating is not lightened in mood by the recognition of signs that he must also have nurtured an at least above-average ambition, as inchoate as its forms or as clumsy as its execution might have been at times, or by an awareness of what must also have been a strong desire to do as he pleased and follow his own ends. Indeed, the very “seriousness” of this combination (virtue plus drive plus self-determination) explains a great deal of the attractiveness of the person Richard Armitage to the first audiences of fans he encountered after the initial broadcast of North & South. To explain his apparent outward identity at this point in his career, however, it is insufficient to say either — or even simultaneously — that he was a modest person who had been pursuing a career in order to please himself, had been not especially successful till then, and was then surprised by his sudden success (a reading for which a great deal of the evidence provided by Armitage speaks) or that he was an ambitious person who covered his desires and his inability to capitalize regularly on his talent with an at-time self-punishing modesty (a reading for which evidence exists if we push Armitage’s own statements slightly into the background and read more from context). These non-exclusive options are complicated by a further factor. For, once he started speaking to fans, it was also apparent that occasional moments that squared neither with “good boy” or “autotelic personality” nor “ambitious man” peeked out. In the beginning, Armitage made little effort to cover these moments and they are most apparent in the first two years of his career after the broadcast of North & South, perhaps before he considered fully or realized what such admissions might mean for others.

[Right: Richard Armitage, behind the scenes on the North & South set (2004). Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

[Right: Richard Armitage, behind the scenes on the North & South set (2004). Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

I’m not sure exactly what to term this facet of Armitage’s personality as apparent in the early materials about him; for me, it fluctuated between “normal guy” and “cheek,” depending on context, between unconscious naïveté and a sort of cautious daring that suggests to more cautious onlookers now a certain amount of unawareness of how observers might possibly read him. It encompasses a number of diverse moments, the chief uniting element of which is certainly humor, amusement at life, and a strong awareness or sense for the absurd that drew in equal measure on a wicked imagination and a familiarity or comfort with edginess that exceeded that of most of his early fan audiences. In his early messages, below the dominant tone of enthusiasm and sincere gratitude for fan support, Armitage frequently seemed young, humorous and open to joking in a way that would not have seemed risky to him from the vantage point of 2004, although it might later have been evident to him that in exposing anything about his personality that might ultimately be controversial, he was potentially playing with fire. He seemed blissfully unaware that some things that normal people might do without comment could now become explosive, if only within the still-tiny arena of his fandom, because he was no longer being judged by the standards of what was acceptable for normal mortals. We might also put in this category matters that might appear as carelessness, coyness, or a subdued tendency to hint with his eyes or his lips that more was going on under his exterior than the reports of virtue and industry suggested.

Richard Armitage would learn only later that unguarded reactions were dangerous, just as humor could be, and so we can see his willingness to laugh and an energy that seems surprisingly youthful for someone in his early thirties much more clearly in 2004 than we will be able to later. The reason that it’s hard to write about this personality facet very exactly now, or say what it meant, is that the actual data are all already so overlaid with fan reaction to them and fans are never neutral. For instance, obviously before he knew women like me were going to start building electronic shrines to him, Armitage was photographed smoking cigarettes between scenes on the North & South set. Smoking tobacco, what is it? A normal quotidian habit, particularly widespread among actors, a way of copying with stress, a venial sin, a deal-breaker for admiring someone? A sign of normality or cheek or human frailty to one person is a matter for strong disapproval or even an unforgivable sin to another. Fans wanted to admire him without reservation, and yet multiple moments in the first two to three years after North & South suggested that Armitage was often either stunned by or winking at the seriousness with which fans took him — perhaps because he wanted fans to lighten up, perhaps because he couldn’t make himself be serious about something he saw as a frivolity, perhaps both. Enjoy this, he seems to be saying from the beginning, don’t be so serious.

[Are we really doing this? Richard Armitage in the interview on the North & South DVD, a piece in which most of his responses are laced with a subtle incredulity. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

[Are we really doing this? Richard Armitage in the interview on the North & South DVD, a piece in which most of his responses are laced with a subtle incredulity. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com]

These things – virtue, personal desire, ambition, and the hard-to-define fourth factor — normality? cheek? naïveté? – were all equally apparent and stood in uneasy relationship to each other, even undermined each other at times during his first video interview on the North & South DVD. Because many of these had potentially different valences, fans were kept guessing, and given a lack of further information, they filled in the blanks according to their own needs and split on the matter of whether the interview made Armitage more attractive or somehow negatively impacted impressions of his performance as Mr. Thornton (my own reaction was the latter). Is Armitage’s statement that he was shocked to be cast a refreshing expression of sincerity from a struggling actor, or a shockingly naïve thing to say in a venue that’s supposed to sell him to an audience? Armitage finds horse poo funny, one learns. Isn’t it sweet that this apparently oh-so-serious man can laugh about something so mundane? Or does that mean that he has a juvenile sense of humor? Is Armitage puerile, or boyish? Is his note that it was pleasant to spend the afternoon filming the train scene the testimony of a shy, sweet romantic, or is there a slightly sexual undertone covered over by the elliptical, almost teasing tone of the statement and Armitage’s general mood of incredulity? Is it amazing that such a good-looking heart throb type can say anything meaningful about acting, or is it rather frustrating that much of what he says about acting in this interview is so little intriguing?

These are the major elements that I can tease out from the personality of the man struck hard, late in 2004, by the surprising, apparently unanticipated success of North & South.

Fans have wrestled with putting these elements in place ever since, and my interpretation is retrospective more than anything — occurring late in the day, and in the absence of ever having met the man myself, even for a second. There’s been a tendency to dichotomize in ways that make me uncomfortable, with the “is he for real?” question occurring with surprising regularity. Can someone be all of these things? Particularly in an age where media sell themselves to us for every second of opportunity we give them, can we trust our impressions of someone who seems unpolished — or is this simply another media trick? The predominance of apparent contradictions in Richard Armitage as they appeared in 2004 confuses the interpreter, and the chief paradox in his personality as apparent to fans — the shy performer — was mixed up with numerous others: the serious worker and king of romantic smolder with the silly sense of humor and lighthearted laugh; the unaware sex symbol; and so on. It might have been easier to buy any of the more “transparent” versions of Armitage on offer — either virtuous Armitage, ambitious Armitage, or autotelic Armitage — had the fourth “normal guy” element not consistently pushed through in ways that suggested that any perception was much more complicated than the viewer realized. I myself am not hostile to paradox, however, or a multiplicity of “both / and” in interpreting a personality, and I also tend to think that any version of oneself that a person puts into the public is on some level “real,” if only in the sense that it reflects an impulse about how one wishes to seem. Most of the research on the development of the self points out that the coherent self develops primarily in response to others, and Armitage’s public self had had little exposure to those demands before 2004. Thus even feigned personalities reflect awareness of personal ideals or attempts at making ideal responses to the demands of others. And, of course, no one fully lives up to his or her own resolutions about how to be all the time — let alone those of others.

My own read, based on this evidence, was that Armitage was all these things in 2004 — possessed of a strong moral sensibility, perhaps a bit superstitious, and involved in thinking at times desultorily, at other times intensely, about something like virtue and karmic balance; modest, polite, self-deprecating; in the midpoint of an arc toward developing more self-confidence that had begun in the RSC but had taken on a more secure footing once he’d started to get more regular work on television; shy or reserved; cooperative, hardworking, ambitious, intense, and sometimes driven by a talent he was not always able to capitalize on in the clinch; pleasure-seeking in ways that he admitted and in ways that he covered up because they would have made him look ridiculous or greedy; and yet also silly at times and unfocused, not entirely sure what he wanted to do; aware of the demands of the business while still shockingly naive or surprisingly (for an actor) in many regards, particularly as regarded how others might be inclined to see him; desperate for professional success and yet ashamed of his desire for it.

But if forced to say what was “real” (following conventional meanings of that word) about Richard Armitage in 2004, as the minor furor over 2004 broke in the UK press, what would I say? I think, based on readings and rereadings and ponderings and re-ponderings:

- Armitage was not, or at least not since his teens, problematically shy in the sense that he could not make friends or talk to strangers. He was, however, not outgoing or an initiator of contact. He possibly felt nervous or uncertain in response to attention and not eager to be at the center of a crowd; he seems to have managed for much of his early life and well into his twenties by flying under the radar except when more was actively demanded from him, and may have used some of this time to retreat into his imagination.

- As an adult actor, Armitage almost certainly struggled with certain kinds of fear in auditions. Early indices and self-reporting suggest that Armitage felt he could only truly relax when he was alone. As a person, by 2004, he was genuinely reserved — although this way of being may have had its roots as a defense mechanism, some evidence suggests that it was innate. By 2004, personal reserve had clearly evolved into a personal style that Armitage used to his benefit. Peeking out from under it occasionally and enigmatically made him more intriguing to viewers.

- Armitage genuinely enjoyed performing, not as an act of self-presentation, but rather as an act of losing the self in a character in whose life he became fully, intensely involved. This may resolve the apparent paradox between shyness and performativity by pointing out that it’s not a paradox; he acted not to gain attention but to lose it. Acting was an opportunity for Armitage to abandon himself, to use his imagination to loosen the bonds of a self that occasionally may have been problematic in real life. It also justified an occasionally apparent unfocused distance from other people in casual interactions that might have been exacerbated by his height and need to lean into conversations. At times, the sliding into characters, as problematic as they were, may have distracted attention from Armitage’s self. To some extent, this possibility explains the effect that Armitage is usually the most interesting interlocutor when he’s talking about the internal nature and motivation of his characters rather than about other matters, because while he can certainly report about other things like historical or literary context, or his own preferences, he is most intensely involved with these entities as mechanisms of dealing with his own condition.

- Armitage was ambitious in the sense that from the beginning, he genuinely saw himself as pursuing artistic goals as he defined these, and sought personal fulfillment through realization of same. Up to 2004, realizing his artistic goals included providing a performance with which he could be satisfied in material he could (re-)define for himself as meaningful, admittedly sometimes through elaborate constructions of complex histories that made minor roles meaningful to him (see above). Moreover, a significant piece of realizing his goals at least since the RSC engagement, and possibly earlier, involved pleasing audiences, so that “great art” was never pursued for its own sake, but rather always held in balance with “good entertainment.” A read of him solely as an artist who wanted to pursue high cultural projects based only on their artistic merits and thus has been miscast in entertainment projects, or alternatively, as someone who wants only to entertain, and thus lacking the desire for high cultural projects, is thus unfairly black-and-white; Armitage was both from at least 2002 or so.

- After years of training and struggle, by 2004, Armitage had developed and was practicing a genuine professional “ethics” of work in the positive sense that most fans understood it, including cooperation, practice, modesty, industry, concentration, intensity. (No single piece of data has ever emerged to contradict this conclusion; Armitage’s coworkers are uniformly positive, even effusive, about having worked with him.)

- Armitage was thus both genuinely industrious in the sense that his upbringing and education would have taught him to work hard, and out of the need to continue developing a career trajectory, but also from a desire to continue to please himself and to benefit from the particular technology of self that acting supplies him.

- Armitage was genuinely (if pleasurably) shocked by being cast in North & South, and then equally stunned by the response to it.

- Armitage was not only not an attention-seeker (see above), he was genuinely unprepared on every level for the sort of attention that came his way as a consequence.

- Part of the reason for Armitage’s surprise in this context can be attributed to a genuine inability or refusal on his part to think about the nature of the success for which he was eager and had worked so hard, but which his overdetermined embarrassment about ego or pride probably caused him to avoid defining very exactly. Admitting that he wanted something seems to have been a real problem for him, to the extent that he might not have allowed himself to think about it too concretely even though he desired it greatly.

- Although Armitage was certainly interested in his appearance, a frugal raising, feelings about certain things being “enough,” and a genuine lack of sustained interest in the trappings of outer notoriety functioned for Armitage as a moral or ethical balance against the possibility that he or others might see himself as attention-seeking.

- Armitage was genuinely grateful for (if also somewhat amazed or occasionally embarrassed by) fan appreciation and activity in response to his work and gratified by the detail of the attention that his first fans gave his work.

- Armitage genuinely believed that the success of the production and the growth in his career in response notwithstanding, he would not need to change his general modus operandi as a person, which meant that he saw no issues at first with admitting to the sort of foibles that every normal person is allowed to have. Moreover, Armitage included speaking about his work, publicizing it, and responding to fans as a function of his person, not as a role. It’s possible that Armitage had never showed as much interest in being himself for others as he had in pursuing his desires, thinking his own thoughts, and going the path of least resistance on a personal level. If that was his personal style — enhanced by reserve — it would be decisively challenged by the reaction to North & South and going forward. Not only was he unprepared for the expectation or demand that he play a version of himself as a role, not only did he act initially as if he were a person responding to other people rather than an admiree responding to his admirers, as attention to him grew larger, he appeared reluctant or passively resistant to playing the role of Richard Armitage.

***

Proposals for addition, revision as of 6/9/2013:

- On shyness, comments Armitage made in spring 2013 that he was shy at parties, but also that his shyness did not pertain to one-on-one situations but rather to large groups of people.

- On fourth personality element (“cheek”?), see increased prominence of this strand during April 2013 Australia Hobbit DVD release press.

***

All text © Servetus at me + richard armitage, 2012. Please credit when using excerpts and links. Images and video copyrights accrue to their owners.

***

Next: Part VII: Richard Armitage starts to play the role of “Richard Armitage.”

[…] To Part VI. […]

LikeLike

My Richard Armitage: An interpretation. Early career to North & South « Me + Richard Armitage said this on December 22, 2012 at 2:40 am |

Fascinating as always. I will be interested to read your thoughts in the next phase of your analysis of RA’s impression management (Irving Goffman), where a juxtoposition of greater self-awareness, media maturity/savvy, and the need for self-editing might come into play as his sphere of fame/celebrity (and fan interest) increases.

LikeLike

Well said, Gratiana! Fascinating to have observed the transitions in public presentation from earliest interviews to especially, the ease with media during the Hobbit tour. The Hobbit casting would appear to have brought a remarkable confidence. I do like the mature Armitage. Cheek and all. 😀

LikeLike

The “cheek” (I wish I had a better descriptor for that) has always been there — it’s interesting that people have found it so problematic, to the point of discounting it at times.

LikeLike

Maybe it is because I am relatively new to all of this, but I just cannot understand why anyone would find the “cheek” problematic. I’ve read many of the early materials and have a hard time finding much that is objectionable. Occasionally he may have divulged TMI for his own good. Is an issue with it generational in the fanbase do you think?

LikeLike

Can’t imagine why anyone would the cheekiness a problem! I love it.

LikeLike

Your comment suggests why “cheek” is not the right word and why “human foibles” or “normality” would be better. Humor is always dangerous — as it’s very likely to offend at least some people. Still, I don’t think that it’s humor (mostly — he doesn’t let us see much of it any more, or at least not till recently) that’s the problem. It’s more that some fans have needed very badly to believe that he’s perfect. And when he isn’t … according to their definition of that …

LikeLike

Well, that is a problem, isn’t it – in that no one is perfect. It is unfortunate that people have perhaps placed him on a pedestal that he cannot possibly stay on – nor should he try to IMHO.

LikeLike

Good for posting this. I’ve had initial reactions to Armitage that have differed a bit from your first posting. However, I’m a slow thinker, and can’t yet comment/analyse on those experiences. Just an early, un-analysed and long time simmering sense of fan response. I long felt Armitage was not just all bout “gentlemanly, humble,” etc. fan-imposed persona. He has that. But it’s not the whole man. And a lot has become more visible, as he has matured, and grown to know his audiences and himself. He’s also an English bloke, and as complex as any of us.

LikeLike

I’m interesting to hear reactions. This is a typology — and really complex already — so undoubtedly there are things I haven’t accounted for.

LikeLike

Pardon my imprecision of language, but I just love this stuff! Even the long sentences and complicated ideas. Especially those. Many of your idea have been floating around in my head in an inchoate mess for some time. So satisfying to see things presented in such a well ordered, detailed fashion. When the holidays and my ripped-out kitchen are over, I hope to comment more substantively. I understand from Angie’s blog that you are a professor. Your course on RA Studies will be a pleasure!

LikeLike

I’m glad it’s helpful to you — and yeah, that is my job — to take a mass of data and try to distill a useful picture out of it. Good luck with the kitchen 🙂

LikeLike

An rarly Christmas present -part iii of the Armitage Bio. Some really interesting stuff here. I think I need to re-read for some proper response. One thing that came to my mind re. career options at this stage of his development was whether he was represented by an agent and in which way that manifests itself in the mive towards television and/or certain parts he tried for and got. It’s a general question, I suppose – how much input does an actor have on his career trajectory. In what way are they guided by their agents and by their own interests.

Great argument and source work, as usual, Servetus!

LikeLike

In the very early days RA used to respond to fan letters at length and I seem to recall that he told someone that he had a discussion with his agent about where he would try to take his career next (it may also haven been an interview that is no longer available). Together they decided that he would try to stay on the chosen track and establish himself as a leading man in TV. Switching to movies would have meant starting at the bottom of the pecking order again. I think the agents already were those he is with now.

LikeLike

@Guylty, rightly or wrongly, my impression would be that following N&S blow-out, a BBC publicist might have taken over the “property” and cautioned – you can’t say this, that, etc. You mustn’t spoil the smouldering image. Fans love it. (OK, we’re suckers for it.) But following publicised since, I think I see a maturity and an EQ/intuitive manner of sneakily taking back control of interviews. What do you think?

LikeLike

A BBC publicist after N&S? The BBC had little interest in promoting RA and N&S, they didn’t even wanted to release the DVD and they didn’t try to capitalize RA’s success. The only job they gave him afterwards was the part of Claude Monet in low budget docu drama The Impressionists. Period costume, yes, but a rather ridiculous one and the character was enthusiastic and smiling, but hardly smouldering. They could have cast him as Rochester or could have created something for him, but they didn’t.

LikeLike

Yeah, I don’t get the impression that the BBC takes much interest in actor careers in general. It was fans who campaigned to have the DVD released and/or released “early.”

I also think there are different issues in image management in the UK and the US, as well as different issues in a theater or TV career vs a film career — because cultural and contextual differences mean that the space for personal expression of one’s own “self” differs strongly.

LikeLike

Afaik, he’s been represented by an agent since the beginning of his TV career at least.

LikeLike

wow, that analysis … am very interested in the second part, very good job ……. good week!

LikeLike

Thanks, shavua tov to you!

LikeLike

Well, the BBC had a tiger by the tail, and missed the stripes. So much for the corporate (Corpserate) mindset…

The Impressionists was a lovely, beautiful film. About Impressionism. Not characters, or acting…

LikeLike

I think they did push it to a more prominent place in their schedule once it was done — Jane will remember this — didn’t it end up on BBC 1 although they hadn’t planned that originally?

LikeLike

[…] training); Part II (Armitage’s career from leaving LAMDA to being cast in North & South); and Part III (pondering Richard Armitage’s identity and personality in […]

LikeLike

My Richard Armitage: An interpretation. Armitage meets “the media,” round one « Me + Richard Armitage said this on December 30, 2012 at 4:50 am |

[…] Notwithstanding this characteristic self-presentation as modest and without significant ego, key ind…. […]

LikeLike

A current Richard Armitage puzzle I’m pondering | Me + Richard Armitage said this on January 14, 2014 at 2:51 am |

Richard’s apparently taken up smoking again. Someone posted a picture on their Tumblr page of him puffing away between takes during filming the Hobbit.

LikeLike

Thanks for letting me know — am I allowed to ask where specifically?

LikeLike

[…] he had never been a dancer or worked in musical theater. So Armitage’s self-narration — which has consistently been one of industry, hard work, and the success of the underdog — reframed the Budapest episode and his dancing afterward as something he needed to do to get […]

LikeLike

richard armitage + dance + “the circus”: a thought exercise on the self and biography | Me + Richard Armitage said this on September 2, 2016 at 4:21 am |

[…] The search for identity and understanding who someone “is” who I only perceive through various mediations. The problems of the sources. This was probably the next most important task of the blog, and it […]

LikeLike

Finneganbeginagain | Me + Richard Armitage said this on September 10, 2021 at 4:41 am |

[…] questions seemed so regularly awkward, stilted, or unprepared, even in the year or so afterward. (Here‘s a reflection on that phase of his identity as seen through the media, written in 2012.) The […]

LikeLike

me + richard armitage’s sexual orientation + the new openness | Me + Richard Armitage said this on April 12, 2023 at 8:15 am |