Which of these things is not like the other? Good Friday 2013 / Shabbat Chol Chamoed Pessach 5773

This post started on Good Friday, finished on Easter Sunday.

Tenebrae when I was a girl is what I always think of on Good Friday. And then there was 2010.

***

They teach it to you from a pup. Above on, Sesame Street, the very first one they ever broadcast.

What belongs and what doesn’t?

What’s part of the pattern? What’s incidental?

INFJs are not great with detail. I know, I know. This doesn’t make sense as a description of me. However, this description of an INFJ sent by a reader explains:

[INFJs] are not good at dealing with minutia or very detailed tasks. The INFJ will either avoid such things, or else go to the other extreme and become enveloped in the details to the extent that they can no longer see the big picture.

And I am plagued by a memory that’s too good. I have to let go of some of it.

Below my week.

***

As I will find out on Thursday, Monday is the day of decision. Gandalf was right about that much. Seven weeks out from my interview, and more than three from the last candidate. I’m surprised they even remember who any of us are.

***

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) sings a song sung to him in his cradle about the patrimony of the dwarves, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Cap from the trailer. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) sings a song sung to him in his cradle about the patrimony of the dwarves, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Cap from the trailer. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com

***

Monday night, we had a raucous first Seder with the Hasidim. 150 people roared out a crazy, loud, Dayenu with all the men dancing. (It is Chabad, after all. The women clapped and hummed along and watched, except me. I sang out loud. Screw it.)

The rabbi was laughing at me, I think. Well, four glasses of wine can make anyone who’s reasonably inclined a little smilier. Later, he introduced me to someone I didn’t know and said, “Yaffa went to Jewish day school and she knows almost as many songs as you do.”

The rabbi’s daughter went outside with one of the yontiff candles to invite Elijah in, accompanied by a thoughtful, pensive chorus of Eliyahu Hanavi. The event went on till the wee hours. Mrs. Pesky and Pesky jr had given up a few hours earlier, so I drove Pesky home around 1 a.m.

When the rabbi said goodbye to us, he asked me, “What’s your Hebrew name?”

I said, “Shoshonah.” I did not say either my matronymic or patronymic.

Driving over the potholes and tears in the streets, we talked about the brokenness of the world. Pesky jr had had a bad day and they almost couldn’t come to the seder. Pesky is worried about their upcoming trip to England. We agreed we want Mashiach to come soon. The rabbi had told us that Elijah, who will precede Mashiach, comes to all seders. We hoped he was at ours.

The streets were silent and peaceful when I drove back. Past the synagogue, where the lights were still on. Into my apartment complex, where most of the lights were off.

***

[Early morning of first day of Passover. Servetus is in bed. Cell phone, which I could have sworn I had turned off, rings. Confusion ensues …]

[Early morning of first day of Passover. Servetus is in bed. Cell phone, which I could have sworn I had turned off, rings. Confusion ensues …]

Mom: So, when will you be home?

Servetus: [silence]

Mom: I googled and your term ends on [date].

Servetus: Yeah. I did sign up to teach summer school, though.

Mom: Why? You’ve never done that before.

Servetus: Just seemed like a good idea financially.

Mom: Does it pay that well?

Servetus: Not as well as the regular term, but I don’t have to do any new preparation. Just grade.

Mom: Oh. Well, when does that end?

Servetus: Not sure — I haven’t looked. I may not get enough students registered. [I wasn’t supposed to admit that, oh shit oh shit oh shit]

Mom: So you’re saying you may not teach it then? When will you know?

Servetus: [Oh shit oh shit oh shit] Not sure.

Mom: I just want to know when you’ll be home.

Servetus: [silence]

Mom: I miss you. And things are so much easier to manage when you are here. You could also babysit a little, help out your brother. I think they’re fighting again [trails off]

Servetus: Yeah.

Mom: Maybe you could teach summer school somewhere up here, if you need money. I can call around and see if anyone needs someone.

Servetus; We’ve been through this before, mom. That’s not how it works.

Mom: Don’t you want to come home?

Servetus: Of course.

Mom: You don’t sound very happy about it.

Servetus: I’m tired. We were up late last night for Passover. I know you get up at five, but I usually get a little more sleep.

Mom: [long, disapproving silence]

Servetus: [oh shit oh shit oh shit I broke the don’t mention Judaism rule plus the “people who admit they sleep past seven are lazy” taboo]

[more silence]

Servetus: I was wondering. I mean–

Mom: You’re not thinking of staying there for the summer? Or were you going to Germany?

Servetus: No, I’m not going to Germany, it’s–

Mom: Well, then you’ll come home, won’t you?

Servetus: [oh shit oh shit oh shit]

[pause]

Servetus: I want to see you. But I was thinking that I might–

Mom: Because your dad really wants you home, too.

Servetus: [getting frustrated] You make it really hard to talk about this.

Mom: What do you mean?

Servetus: Can I finish my sentence?

Mom: [sighs]

Servetus: It’s just [heartbeat, heartbeat, heartbeat, heartbeat, heartbeat] it’s just that I don’t know if I can spend a whole summer in the same house with Dad.

Mom: What do you mean?

Servetus: After Christmas.

Mom: I don’t understand.

Servetus: I [heartbeat, heartbeat, heartbeat, heartbeat] don’tknowifIcanliveinthesamehousewithanalcoholicanymoreforawholesummer.

Mom: You’re exaggerating. It’s not that bad.

Servetus: [oh shit oh shit oh shit oh shit] I think I make things worse sometimes. For you.

Mom: [silence, then:] I just don’t know when I’ll see you again.

Servetus: I’ll come for a little while. Or I can stay at [piano teacher’s] house. She actually offered once.

Mom: You can’t come visit us and not stay here. Everyone would know.

Servetus: Not if you don’t say anything.

Mom: You want to come visit us and stay somewhere else? When would we see you?

Servetus: I don’t know, I just. [pause] I just need more control over my environment.

Mom: Well, you just have to control yourself first. Not get so angry. You’re an adult, you’re responsible for your own feelings.

Servetus: I know, but no feelings I have about this are actually okay with either of you.

Mom: Your feelings are so out of proportion to the actual situation.

Servetus: [thinks — they aren’t, you just have been living with it for over fifty years so you don’t notice anymore] When I spend too long with Dad, I start to wonder if I am crazy.

[silence silence silence]

Mom: I know that when I’m gone, you’re going to abandon him.

Servetus: [oh shit oh shit oh shit oh shit]

Mom: And now you don’t even want to come to see me.

Servetus: I do want to see you. Really! I just need to feel safe when I am there.

Mom: That’s nonsense. It’s perfectly safe here.

Servetus: [silence]

Mom: So, when will you be home?

Servetus: I have to get going, I’m going to be late for synagogue.

***

Hallel at Shacharit on Pessach is really rousing, really cheering. Ours didn’t have guitars, but the atmosphere was similar.

***

One of my favorite books, William Gibson’s Pattern Recognition, physically dropped from my bookshelf Monday afternoon as brushed past it when I went to my office.

One of my favorite books, William Gibson’s Pattern Recognition, physically dropped from my bookshelf Monday afternoon as brushed past it when I went to my office.

I picked it up, put it in my bag, and started to reread it Tuesday afternoon when I got home from shul.

Wikipedia describes the theme of the novel: “The novel’s central theme involves the examination of the human desire to detect patterns or meaning and the risks of finding patterns in meaningless data. Other themes include methods of interpretation of history … and tensions between art and commercialization.”

I’ve always liked the protagonist of the story, Cayce Pollard. She was 32 in 2003, when the story was published, and I was 34. And Cayce has reactions like mine. For instance, the observations she makes about jetlag and landing in foreign countries are almost exactly the ones I’d note. More importantly, she’s been granted odd, intuitive, preternatural gifts, but has to protect herself from a severe, almost allergic phobia relating to items with which she regularly works in order to do her work. Her job is figuring out what trends are going to take off so that they can be branded and monetized. But she’s allergic to visual images of brands.

Exposure to the very thing she focuses on leaves her with an emotional reaction as severe as anaphylactic shock.

***

A mining dwarf discovers the Arkenstone, which both symbolizes Erebor, and also attracts the dragon Smaug, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. My cap.

A mining dwarf discovers the Arkenstone, which both symbolizes Erebor, and also attracts the dragon Smaug, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. My cap.

***

The conversation with mom left me drained. I didn’t want to go to the second Seder, but I didn’t feel I could call in sick. I stopped and bought flowers for the table and a card for the Fuzzies.

“May you have freedom from whatever may be enslaving you,” I wrote, “and thank you for including me at your table.”

The second Seder, with the Fuzzies, the Peskies, and the Fuzzies’ families and a few other people, is pleasant and familiar and unremarkable, except in two ways. First, it’s really rare for me to celebrate the Seder two years in a row with most of the same people. Second, in that Pesky quotes a Midrash according to which 80 percent of the Israelites in Egypt chose to stay there rather than leave their homes and their enslaved misery to cross the Red Sea to an uncertain future.

Mr. Fuzzy’s mother says, “Can we eat already?” every ten minutes. Mrs. Fuzzy is conflicted about singing Jewish songs, and asks everyone if they would mind singing “Simple Gifts” instead of “Dayenu,” which is really violent toward non-Jews. She has a point. The violence in the Haggadah that accompanies Jewish freedom is not for the faint of heart. We compromise and sing both.

After dinner, Pesky and I look at each other. “If you could sing one more song,” he said, “What would it be?’

“All the world is a very narrow bridge,” I say, “And the main thing is not to make oneself afraid.”

Pesky says, “I love that song. Carlebach, isn’t it?”

We sing the hell out of it. Eventually, Mrs. Fuzzy comes back to the table to sing with us, and the Peskies and I and Mrs. Fuzzy and her sister sing every Jewish song we can think of.

“Thanks, you guys,” Mrs. Fuzzy says. “I need to learn more songs.”

“Come to shul,” Pesky urges.

Mrs. Fuzzy frowns.

It’s past midnight, again, when we leave.

***

The song I’m listening to on infinite repeat as I write this.

“Climbing up on Solsbury Hill

I could see the city light

Wind was blowing, time stood still

Eagle flew out of the night

He was something to observe

Came in close, I heard a voice

Standing stretching every nerve

Had to listen had no choice

I did not believe the information

(I) just had to trust imagination

My heart going boom boom boom

“Son,” he said “Grab your things,

I’ve come to take you home.”

[I can’t help but point out that an eagle will rescue Thorin, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Apophenia? See below.]

***

On Tuesday evening, I am spotted by three former colleagues on their local television news, walking past the most striking landmark on the campus of the university I used to work at, wearing a red shirt.

***

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) reacting to Bilbo’s question about the fate of the pale orc: “Slunk back into the whole whence he came.” The subsequent glances of the other characters reveal that they know this is not true, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. My cap, edited to make Thorin’s face more visible.

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) reacting to Bilbo’s question about the fate of the pale orc: “Slunk back into the whole whence he came.” The subsequent glances of the other characters reveal that they know this is not true, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. My cap, edited to make Thorin’s face more visible.

***

I go to shul again Wednesday morning, and come home again in the afternoon to read.

I go to shul again Wednesday morning, and come home again in the afternoon to read.

In the book, Cayce’s father disappeared on September 11, 2001. Her mother reacts to the lack of closure about her husband’s whereabouts by combing EVP frequencies to obtain a message from him. Cayce is highly sensitive to patterns and data that belong together, which makes her successful at predicting what will be stylish in the future; Cayce’s mother, in contrast, has apophenia — she seeks meaningful connections between random, unrelated data in order to resurrect the past.

I nod when I read about how Cayce tries to avoid opening her mother’s emails and then does it anyway.

What I’d always loved about this book are the images that Cayce remembers as connected to the collision of the airplanes with the Twin Towers — the way that the collision of the Twin Towers is meaningful, and the falling of a dried rose petal is random, and the fact that these data are irretrievably captured together in her memory.

I also appreciated the book’s articulation of a notion of history after 9/11:

“Of course,” he says, “we have no idea, now, of who or what the inhabitants of our future might be. In that sense, we have no future. Not in the sense that our grandparents had a future, or thought they did. Fully imagined cultural futures were the luxury of another day, one in which ‘now’ was of some greater duration. For us, of course, things can change so abruptly, so violently, so profoundly, that futures like our grandparents’ have insufficient ‘now’ to stand on. We have no future because our present is too volatile. […] We have only risk management. The spinning of the given moment’s scenarios. Pattern recognition.”

Cayce blinks.

–William Gibson, Pattern Recognition (New York: Berkley, 2003), p. 57.

Although, honestly, for me and my generation, that state of affairs preceded 9/11 by quite a bit. Still, we all are engaged in constant, frantic attempts to figure out what the data swirling around us might mean.

You could say that one of the main things historians do is pattern recognition. I am a historian of Erebor against Erebor. Am I not?

***

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) ponders Bilbo’s statement that the dwarves might not mind wandering about because they have no home, in The Hobbit: The Unexpected Journey. My cap, again edited to reveal more of the facial expression.

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) ponders Bilbo’s statement that the dwarves might not mind wandering about because they have no home, in The Hobbit: The Unexpected Journey. My cap, again edited to reveal more of the facial expression.

***

I go to work very late Wednesday afternoon, late enough to salve my conscience about ending the work-free days for Passover a bit early, to hold my office hours, because I have to teach in the evening, as soon as the sun has set.

I turn on my computer and learn from facebook and two emails that I’ve been seen on my last campus.

“Were you here for Passover?” one former colleague writes. “I’m disappointed you didn’t call.”

“No, I was celebrating the Passover last night here,” I write back.

“Are you in town?” another emails me to ask. “Can we get together?”

“No,” I write back. “I have not been resurrected. I have witnesses.”

***

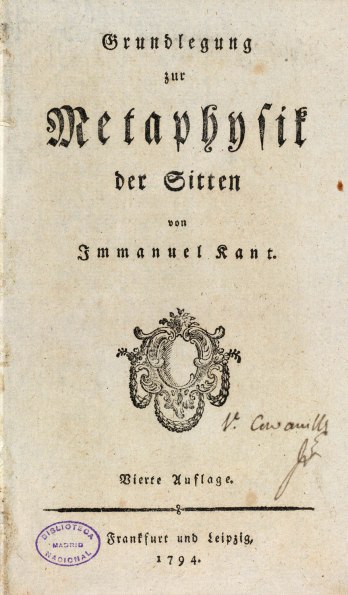

No one comes to office hours. My research seminar students are reading Immanuel Kant’s Fundamental Principles of a Metaphysics of Morals (1785). For non-initiates: it’s an attempt to derive a justification for morality entirely based on unquestionable axioms, independently of experience or case studies.

No one comes to office hours. My research seminar students are reading Immanuel Kant’s Fundamental Principles of a Metaphysics of Morals (1785). For non-initiates: it’s an attempt to derive a justification for morality entirely based on unquestionable axioms, independently of experience or case studies.

In the book, Kant proposes that a morally good act is determined solely on the basis of a good will (not upon either its ends or its actual outcomes), and famously articulates the so-called categorical imperative, the idea that one is not acting morally (and thus should not act) unless one can turn the action into a universal law. If one cannot will that all do the same thing as one does oneself, one should not act.

This stuff is not what catches me on this readthrough, however, although I know that my students will not have understand his main points, and we will have to go over the argument step by precious step. Instead, I’m caught by Kant’s remarks in the opening pages of the work that acting morally is not likely to make one happy, and that if the point of Nature were to make man happy, then instinct would be better gauged as the basis of morality. But morality is first achieved, Kant counters, when following duty, we act according to its rules independently of our own self-interest. Doing so is difficult, as he notes, because even altruism can be in one’s interest.

Can we be happy and moral? At first Kant seems to think not.

The passage that strikes me tries to resolve this apparent problem by redefining personal happiness as a facet of duty:

to secure one’s own happiness is a duty, at least indirectly; for discontent with one’s condition, under a pressure of many anxieties and amidst unsatisfied wants, might easily become a great temptation to transgression of duty. … in this, as in all other cases, [remains] this law — namely, that [one] should promote his happiness not from inclination but from duty, and by this would his conduct first acquire true moral worth.

I have a duty to be happy, even if I’m not happy about being happy?

I realize I am going to have just as much trouble understanding this text as my students.

***

I walk out of the building after class, six hours later. They didn’t understand it. Worse, they couldn’t make any connections between this reading and the stuff we’d read the previous weeks. This class is way too hard for them; I shudder to think what their research papers are going to look like.

I walk out of the building after class, six hours later. They didn’t understand it. Worse, they couldn’t make any connections between this reading and the stuff we’d read the previous weeks. This class is way too hard for them; I shudder to think what their research papers are going to look like.

I hear the beer refrain in my head. That place in the center of my brain that sings so loudly, “Bathe me in malt.” And has been saying it interminably for seven weeks.

It’s Passover. No fermented grains for a week.

It’s just the lure of the forbidden, I tell myself. Because I have no taste for wine. Even though I’ve been drinking it for two days now, and have some at home.

And yet I suspect: I crave beer for the same reason my father drowns himself in it. Failure, inadequacy, never being good enough. Not ever knowing what to do, but knowing I have to get up again the next morning anyway and watching the days fly by with no solutions.

Not wanting to look at much of that very exactly.

I drive home. I unlock the door of the box I live in, drop my bag on the sofa, lock myself in against the night. I strip naked in the darkness; I creep under the covers; I think about Richard Armitage and touch myself; I fall asleep.

***

To keep in silence I resigned

My friends would think I was a nut

Turning water into wine

Open doors would soon be shut

So I went from day to day

Tho’ my life was in a rut

“Till I thought of what I’d say

Which connection I should cut

I was feeling part of the scenery

I walked right out of the machinery

My heart going boom boom boom

“Hey” he said “Grab your things

I’ve come to take you home.”

***

Thursday morning. I walk into my office. A message: Erebor has called to announce they have decided and will call. When is unclear. I’m teaching or preparing all day. I drop them an email to say when I’m available.

Thursday morning. I walk into my office. A message: Erebor has called to announce they have decided and will call. When is unclear. I’m teaching or preparing all day. I drop them an email to say when I’m available.

No phone call back, so I do the reading on the Thirty Years’ War for class discussion.

I contemplate the journal entries of a soldier who transported his family around with him because that’s how things worked at the time. Our soldier’s wife had four children as camp follower and all four died, three of them unbaptized. Every time, the soldier noted a cross in his journal next to the gender of the child (and in the one case, the baptismal name) and then wrote, “May [s/he] receive a joyous resurrection.”

In class, we discuss the extent of the man’s emotionality and/or religiosity. Did the Thirty Years’ War make people more or less religious? How attached was he to these babies?

In class, I ask a young woman who is facebooking to shut off her computer and take part in the discussion. She slams it shut with a loud sigh.

Someone points out that the broadsheet in our collection that complains about debased coinage and wartime inflation starts with an insistence that the Last Days are coming soon. Is this religiosity? Or powerlessness? Did they really believe the Messiah would come in their own times?

Facebooking student pulls out her phone to text. I ask her to leave and to come back next time ready to participate in the discussion.

She whines, “This class is really boring.”

Before I can manage to stuff my fingers in my mouth, I reply, “Bored people are usually boring people.”

The class laughs.

She slams the door as she leaves.

I have broken my number one rule of teaching — never shame a student — and its corollary — never ever use my power to embarrass a student in front of his/her peers.

I feel like absolute shit.

I breathe out deeply, and ask if we can come to any conclusions about the “crisis mentality” of the age based on the sources we have read. Discussion picks up, and some of the students formulate the Ariès thesis on their own. If you are used to children dying, perhaps you are not so upset about it? Maybe you don’t get invested in things that you figure might never come to fruition?

“I don’t know,” a young woman remarks. “The mortality rates you told us about in lecture say that he should have expected half of his children to die. But all of his children?”

The students are divided in their opinions. How can anything be a crisis if the unpleasantness reflects a more-or-less constant atmosphere?

We leave. Their papers are due next time.

***

I go back to my office. The light on my phone is flashing.

I go back to my office. The light on my phone is flashing.

I write facebooking student an immediate email to apologize for my cruel remark, and ask her to see me before the next session.

I ponder whether I should apologize to her in front of the class. I decide I’ll ask her if she would like me to.

I listen to the message. Erebor again. The Dean informs me that he will try to call me today, but that if he can’t get me today, he’ll have to call me Monday. Easter and all. I don’t know if I can take another weekend.

I pull out my PowerPoint and notes on witchcraft and witchcraft accusations as social drama and consider the evidence for this in the sources we read for this class.

***

In class, I lecture on, and then we discuss, an account of witchcraft from late-sixteenth-century France. An old, probably indigent woman, Françoise Secretain, asks her neighbors if she can stay with them in the house that night. The neighbor woman declines, saying her husband isn’t home. When the old woman persists, the neighbor woman capitulates. Shortly thereafter, the neighbor’s young daughter

In class, I lecture on, and then we discuss, an account of witchcraft from late-sixteenth-century France. An old, probably indigent woman, Françoise Secretain, asks her neighbors if she can stay with them in the house that night. The neighbor woman declines, saying her husband isn’t home. When the old woman persists, the neighbor woman capitulates. Shortly thereafter, the neighbor’s young daughter

was struck helpless in all her limbs so that she had to go on all fours; also she kept twisting her mouth about in a very strange manner. She continued thus afflicted for a number of days, until on the 19th of July her father and mother, judging from her appearance that she was possessed, took her to the Church of Our Saviour to be exorcised. There were then found five devils, whose names were Wolf, Cat, Dog, Jolly and Griffon; and when the priest asked the girl who had cast the spell on her, she answered that it was Françoise Secretain, whom she pointed out …”

-Henry Boguet, An Examen of Witches, trans. E. A. Ashwin from the French, based on 2nd ed. of 1602 (London, 1929), p. 1. [Note illustration is from 13th ed. of 1610.]

The little girl admitted that Françoise gave her “a crust of bread resembling dung and made her eat it, strictly forbidding her to speak of it, or she would kill her and eat her (those were [Françoise’s] words)”.

For the benefit of the class, I note the appearance of Victor Turner‘s classic stages here: breach (the neighbor woman refuses to give freely the asked-for hospitality); crisis (the girl becomes afflicted with symptoms of demonic possession); redress (the family takes the girl to be exorcised, and accuses Françoise of witchcraft). And then there’s the final step according to Turner: reintegration.

A student objects. “But the redress included torturing Françoise to get her to admit the accusations.”

I concede this is true.

Another student remarks, “You didn’t say this, but aren’t you implying that she is ‘reintegrated’,” — and here she makes scare quotes with her fingers — “by getting burned to death?”

Fifty heads nod. The readiness of these students to sympathize with the victims has pushed me into defending the authorities to an extent I am bothered by. Some students have doubtless come to view me as heartless. They have no idea. One reason I prefer intellectual to social history is that I am tortured by the fragments of the histories of these people I run across in my reading. Traditional social history, as much as it claims to rescue ordinary people from historical oblivion, by using people as fodder for general patterns, frequently truncates the individual narrative when the point it illustrates has been sufficiently demonstrated.

I looked up what happened to Françoise last year, and then dreamt of her, burning.

“For the early modern Christian,” I remark, “the world did not end with the death of the individual. Just as the Inquisitions reconciled heretics with the church by burning them, so the torture and execution of Françoise reintegrates her into the normal realm of the Christian cosmos — admitting her actions, and possibly repenting them, she goes to her death to be socially reintegrated as a denizen of Heaven, Purgatory, or Hell.”

“Can you really believe she’s saying that just based on who she was, socially, Françoise could have done nothing to avoid her fate?” the second student demands of the class, even more outrage in her tone.

The students turn to me, wanting an answer.

“What do you think?” I ask, ever enigmatic.

Inside I am resentful.

“I can’t even make meaning for me,” I muse, walking back to my office, and realizing I can’t have a Coke (corn syrup). “How can I make it for you, too?”

When the fate question pops back into my mind, I curse myself.

Papers are due next time.

***

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) rescued from Azog at the last second by a giant eagle, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. The picture Obscura chose from the caps I made for her. My cap.

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) rescued from Azog at the last second by a giant eagle, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. The picture Obscura chose from the caps I made for her. My cap.

***

[Right: The entry to Erebor, from The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey]

[Right: The entry to Erebor, from The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey]

I walk back to my office.

The phone is flashing.

Obscura comes out via email as now having a blog. Now I know why she wanted the screencaps of Thorin.

I listen to the message. It again threatens not to tell me till Monday. I call back again and tell them I need to hear from them today, even if only via email, and I send an email to that effect as well. I give Obscura a few basic suggestions about fiddling with her blog. She says she’s going to class. I page, a bit listlessly, through Armitageworld.

The phone rings, finally, about an hour later.

“Michaela?”

“Bill.”

“I’m just calling to update you as to where we are in our search. [Long, unnecessary repetition of procedural steps taken.] We made a decision on Monday, and an offer on Tuesday, and that offer has been orally accepted, and a written offer has gone out, and we have every reason to assume it will be accepted in writing.”

“Oh,” I say. “Good to know. My chair wants me to commit to a contract, so I’m going to go ahead and do that and make him happy.”

Bill seems a bit puzzled about my flat affect, though: What does he want me to say? It’s a status trick, though, a weapon of the weak — when the less powerful person in an interaction is silent in the face of a message of which the powerful person is ashamed, the powerful person becomes voluble. The more powerful person wants to be forgiven for the transgression, even if s/he’s not sorry.

The impending apology I will have to make to my facebooking student crosses my mind, fleetingly.

“You gave us a tremendous gift with your interview,” Bill says. “We were all very impressed with how much time you took to learn about us and how exceptionally well prepared you were. We’ve rarely seen a classroom session so energetic,” he says, “and your presentation was extremely learned.”

“Thanks,” I say.

I gave you the gift of realizing you didn’t want me, I think. And myself the gift of yet another painful look at the land I will never inhabit.

“It was an extremely difficult decision,” Bill rushes on, apparently relieved that I am talking, “but we had to consider all of the needs of the program, and so we offered the job to someone else.”

I am damn well not going to sympathize with him that yet I again, I have failed to meet someone’s needs.

“It was a very thought-provoking experience on my side,” I say.

“When we have the written acceptance, we’ll let you know officially that the search is finally over,” he says.

“No rush,” I said. “Thanks for letting me know today.”

“Well, then,” he said. “Best wishes for your future endeavors.”

“Thanks,” I say. “Happy Easter.”

He pauses. “Yes,” he says. “Thank you.”

***

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) saved by the eagle after his encounter with Azog the Defiler, lies unconscious, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Having made caps for Obscura, this one was handy as a choice to post in the aftermath of my conversation with Erebor.

Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage) saved by the eagle after his encounter with Azog the Defiler, lies unconscious, in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Having made caps for Obscura, this one was handy as a choice to post in the aftermath of my conversation with Erebor.

***

I drop Gandalf an email to let him know the result. “We were both right,” I write. “They decided Monday — and against me.”

I drop Gandalf an email to let him know the result. “We were both right,” I write. “They decided Monday — and against me.”

As I prepare to walk out of my office, I pick up my keys.

I unclip the replica key to Erebor and leave it lying on my desk.

The key ring is much lighter.

As I walk out of the building, I do not hear the beer refrain. I do not hear anything at all. I am not hungry or thirsty or happy or sad.

I drive home and sit on the sofa and finish the reread of Pattern Recognition as the sun sets. I still have no appetite.

Eventually, I lean over to switch on the lamp and think, “A normal person would want to talk to someone right now.”

I call Didion. Eventually she calls me back. She’s in NYC for a professional thing that’s just ended, and I tell her the news. She commiserates. We chat about this and that, and then talk about what she could do in mid-town that night.

“If you go to the theater district,” I say, “maybe you could run into Richard Armitage in the audience of a play or something.”

She laughs. “Is he here?”

I say, “Possibly.”

She says, a kidding tone in her voice, “Well, where? Don’t you know?”

I say, smiling, “No. Too bad you don’t have friends with better information, so you could find out.”

***

The last time I reread it must have preceded Armitagemania. And so I’d been suppressing a main theme of the work, for Cayce is an avid fan. She follows clips of a film (“the footage”) that pop up on the Internet from time to time, around which an international assemblage of fans groups to analyze and discuss their origins, themes, and meaning.

The last time I reread it must have preceded Armitagemania. And so I’d been suppressing a main theme of the work, for Cayce is an avid fan. She follows clips of a film (“the footage”) that pop up on the Internet from time to time, around which an international assemblage of fans groups to analyze and discuss their origins, themes, and meaning.

Gibson describes Cayce’s experience of the “footage” fandom this way:

Always, now, the opening of an attachment containing unseen footage is profoundly liminal. A threshold state.

Parkaboy has labeled his attachment #135. One hundred and thirty four previously known fragments— of what? A work in progress? Something completed years ago, and meted out now, for some reason, in these snippets?

She hasn’t gone to the forum. Spoilers. She wants each new fragment to impact as cleanly as possible.

Parkaboy says you should go to new footage as though you’ve seen no previous footage at all, thereby momentarily escaping the film or films that you’ve been assembling, consciously or unconsciously, since first exposure.

Homo sapiens is about pattern recognition, he says. Both a gift and a trap.[…]

[Cayce] Mouse-clicks. How many times has she done this? How long since she gave herself to the dream? Maurice’s expression for the essence of being a footagehead. […]

The one hundred and thirty-four previously discovered fragments, having been endlessly collated, broken down, reassembled, by whole armies of the most fanatical investigators, have yielded no period and no particular narrative direction. Zaprudered into surreal dimensions of purest speculation, ghost-narratives have emerged and taken on shadowy but determined lives of their own, but Cayce is familiar with them all, and steers clear. And here […] she knows that she knows nothing, but wants nothing more than to see the film of which this must be a part. Must be. […]

She clicks on Replay. Watches it again.

William Gibson, Pattern Recognition, pp. 22-24.

Cayce’s employer, who wants to exploit the marketing potential of the footage, gets her to track down its composers. (This theme of love of art vs. commercialism also played a role in my week, but I’ve decided to cut that strand out of my story today.) She has mixed feelings about this, but by chasing down the source of the footage, Cayce is able to generate a little more information about her father’s fate on 9/11.

There was still no evidence, the unknown and awkwardly translated writer concluded, that Win was dead, but there was abundant evidence placing him on or near the scene. Additional inquiries indicated that he had never arrived at 90 West.

The petal falling from the dried rose.

Someone raps lightly on the door.

[…] “What’s up?”

“I’m reading about my father. I’d like some water, please.”

“Did they find him?”

[…]

“No.” She drinks, splutters, starts to cry, stops herself. “Volkov’s people tried to find him, and got a lot further than we ever did. But he’s not here,” she holds up the blue sheets, “he’s not here either.” And then she starts to cry again,

William Gibson, Pattern Recognition, pp. 349-350.

The need she feels to keep looking at the data for meaning. The impossibility of getting to meaning about her father. Having to accept that she will never have an answer.

Although the book decides that the fate of Cayce’s father is not the decisive problem — that’s the footage. And on that, it will give her an answer …

***

Friday, I go through the email I haven’t read all week and start compiling Legenda. While I’m doing this, I meet with a bunch of students about their papers at my favorite café. I realize about two hours after it ends that I missed a curriculum meeting in my department. I drop my chair a note and apologize and tell him why. He tells me he’s sad for me but happy for himself.

Friday night, instead of going to shul, however, I find myself watching Spooks 7.8.

This episode killed me when I saw it the first time. I have a blog post about that I’ll have to publish some day. Friday night, I wonder — in the end, was it really worth it? The loyalty? Through all those years of prison?

I wonder, too: was there ever an alternative?

***

In the end, although Cayce is not able to learn anything more about her father, she does find the maker of the film and manages to watch at work.

In the end, although Cayce is not able to learn anything more about her father, she does find the maker of the film and manages to watch at work.

In the darkened room whose windows would have offered a view of the Kremlin, had they been scraped clean of paint, Cayce had known herself to be in the presence of the splendid source, the headwaters of the digital Nile she and her friends had sought. It is here, in the languid yet precise moves of a woman’s pale hand. In the faint click of image-capture. In the eyes only truly present when focused on this screen.

Only the wound, speaking wordlessly in the dark.

William Gibson, Pattern Recognition, p. 305.

I had never noticed that last line until this reading.

It’s a wound, at the center of the creativity?

At the center of the search for meaning, an aporia that only clicks and types and photographs and looks.

***

Saturday, shul. From the Torah reading for Chol HaMoed Pessach:

18 Moses said, “I pray thee, show me thy glory.” 19 And [G-d] said, “I will make all my goodness pass before you, and will proclaim before you my name ‘The Lord’; and I will be gracious to whom I will be gracious, and will show mercy on whom I will show mercy. 20 But,” [G-d] said, “you cannot see my face; for man shall not see me and live.” 21 And the Lord said, “Behold, there is a place by me where you shall stand upon the rock; 22 and while my glory passes by I will put you in a cleft of the rock, and I will cover you with my hand until I have passed by; 23 then I will take away my hand, and you shall see my back; but my face shall not be seen.”

—Exodus 33: 18-23 (RSV)

I can’t wait for the direct message because there is none. I will never see the face of G-d and live.

I am never going to see how this makes sense, except from the rear. Some vague perception. Nothing definitive. The pattern will never, ever reveal itself. G-d G-dself is holding his hand in front of my face, so that I will never see it.

For Moses as for Cayce, there is no presence.

***

During the Torah service, a spat erupts in the men’s section — the rabbi wants to call his father-in-law to the Torah, and he doesn’t want to be called. The in-laws have been here for the last three weeks, and it’s been easy to see the tension between father- and son-in-law.

During the Torah service, a spat erupts in the men’s section — the rabbi wants to call his father-in-law to the Torah, and he doesn’t want to be called. The in-laws have been here for the last three weeks, and it’s been easy to see the tension between father- and son-in-law.

Plus: Old man as toddler. I admit, the old guy annoys me. But he clearly loves his wife, who’s sitting next to me, as for the last few weeks. Her vision is too weak to read the prayerbooks and chumashim we have. He makes sure that she has the only large print materials this shtibl owns, and whenever we diverge from the usual pattern, he comes over to make sure that she’s in the right place.

The dispute persists for a good two minutes. They don’t want to fight “in front of” our little congregation, I guess, so it’s all in Yiddish. The rabbi’s mother-in-law, who’s seated next to me in the women’s section, begins to cluck. Eventually the aliyah is pressed on the old man.

I snort involuntarily when the old man gives in. The old man rises to bless the Torah and I say the response.

But the rabbi’s mother-in-law notices my snort, touches my elbow, and says, in a surprised tone, “? קאַנסטו רעדן יידיש”

I look at her, and pinch my lips between my teeth. What to say? I say nothing.

She persists: “.אָבער דו פֿאַרשטייסט”

I look at her again and can’t hide that I understood what she said.

I prevaricate.

“.איך האָב גוווינט אין דייטשלאנד” I say.

She nods and pats my hand. I can see the question in her eyes, but the Torah reading is over — the aliyot are short on Chol Hamoed — and her husband’s now quibbling with the way that his son-in-law is saying the blessings for him and his family members that follow the reading.

Meanwhile, my flight reflex is triggered, as it always is by personal questions in settings like this.

Like the dwarves, I do not belong anywhere except in a dark mountain that’s controlled by a dragon and I can’t even get myself into it.

I’m already thinking about how to get away. When the next piece of information falls, during the prophetic reading.

***

From Friday night, but it fits here, or else earlier in the story, next to the bits about my colleagues seeing me on TV last night in a city that I haven’t set foot in in almost two years.

This was the line that killed me when I saw it the first time. As Didion will probably understand better than anyone.

I may ask myself what to keep and what to give away, but in the end, it’s not my decision. Everything will be taken away.

***

From the Haftarah for Chol HaMoed Pessach:

The hand of the Lord was upon me, and he brought me out by the Spirit of the Lord, and set me down in the midst of the valley; it was full of bones. […] 3 And he said to me, “Son of man, can these bones live?” And I answered, “O Lord God, thou knowest.” […]

11 Then he said to me, “[…] Behold, they say, ‘Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are clean cut off.’ 12 Therefore prophesy, and say to them, Thus says the Lord God: Behold, I will open your graves, and raise you from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you home […]. 13 And you shall know that I am the Lord, when I open your graves, and raise you from your graves, O my people. 14 And I will put my Spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you in your own land; then you shall know that I, the Lord, have spoken, and I have done it, says the Lord.”

from Ezekiel 33:1-14 (RSV)

Ezekiel, dude. That’s the thing I want to say to G-d, the next time I hear a rhetorical question. In essence, “Stop posing me problems that you know the answer to, but I don’t.” Especially if I will never see your face.

Yet another promise.

A promise that I’ll only know fulfilled when it’s over.

***

Last verse.

When illusion spin her net

I’m never where I want to be

And liberty she pirouette

When I think that I am free

Watched by empty silhouettes

Who close their eyes but still can see

No one taught them etiquette

I will show another me

Today I don’t need a replacement

I’ll tell them what the smile on my face meant

My heart going boom boom boom

“Hey” I said “You can keep my things,

they’ve come to take me home.”

***

The prayer that concludes every service.

“Do not fear sudden terror, nor the destruction of the wicked when it comes. Contrive a scheme, but it will be foiled; conspire a plot, but it will not materializ, for G-d is with us. To your old age I am with you; to your hoary years I will sustain you; I will sustain you and deliver you. Indeed the righteous will extol Your Name; the upright will dwell in Your presence.”

In the spirit of honesty, I feel obligated to point out that the phrase “for G-d is with us” [כּי עִמָּנוּ אֵל] is the source of the name “Immanuel,” Kant’s first name. Noting this, however, is an index of the growing apophenia that is taking over this post.

***

When the service is over, I kiss the rabbi’s mother-in-law on the cheek, and say, “Gut shabbes,” and she says in English, “You’ll come to Kiddush.”

I lie. I say, “No, I’ve gotta go home and call my mom.” Because the mother is holy in Judaism, and concern for one’s mother excuses the worst gaffes, like not staying for lunch on Chol Hamoed Pessach.

She says, “Your mother, she’s coming?”

I say, “No,” but there must be a horrified expression on my face, because she looks at me sadly, and kisses me on the cheek again. “A gute Moed,” she says. “Maybe I’ll see you next week?”

Meanwhile, the men are dancing to yet another song, including Pesky and Pesky jr., and I take the opportunity to dash before anyone else can notice I’m gone. I don’t even pause to talk to Pesky — I just go.

When I’ve driven six blocks away, I pull over and park the car till the anxiety abates.

***

When I sit down to write this morning, I find this interview linked on RichardArmitageNet.com.

The comparison of Thorin to Moses seems unavoidable.

***

This is the problem with pattern recognition — there is always more and more and more data.

The data are too transfixing. My allergy to the subject lames me; entropy brings me to apophenia.

Isn’t it deciding what that pattern is, though, that creates apophenia? Once you decide the pattern, the data rearrange themselves into meaning? And thus everything else becomes incidental, even though there’s so much of it?

Is the argument for pattern recognition one made from first principles, or from case studies?

Do the data make the pattern, or the pattern make the data?

I have to make myself stop analyzing all this data and asking what the data means. I have to decide for a pattern, and tell the data what it means.

***

As I pose my finger over the “publish” button on this post, sitting in my favorite café, a young man stops at my table. He says, “Hey, Dr. Servetus!”

As I pose my finger over the “publish” button on this post, sitting in my favorite café, a young man stops at my table. He says, “Hey, Dr. Servetus!”

It’s a student who sat on the far right of the classroom in the first class I taught here, in Fall 2011. Josh, I think his name is. I wrote him a brief recommendation last December, assuring the local diocese that he was a competent and faithful student.

“Hi,” I say, and he shakes my hand. “I don’t know if you remember my name.”

“Sure,” I say. “Josh. Even if I forgot, though, it’s written on your coffee cup.”

He laughs.

“You’re studying to be a Catholic priest now, right?” I ask. “How’s it going?”

“Great,” he says. “I love it. I’m so glad I ran into you. I use all that intellectual and religious history stuff I learned in your class all the time, Anselm, Aquinas, Luther, Descartes, it’s always coming up in our courses now.”

“That’s great,” I say, “Thanks for letting me know. I’m always glad to hear that people think there was a point. And you really like seminary?”

“Totally,” he says, with a huge smile. “I finally feel like I’m doing something that matters.”

I think of him as “Father Josh,” in the years down the road, playing basketball with the kids in his parish and visiting the sick. “That’s important,” I agree.

He grins again as he turns to go. “Happy Easter, then!” he says, and then hesitates. He remembers that I’m not a Christian, and his face falls a little.

“Happy Easter, Josh,” I say, reassuringly, and smile.

***

As I finally push the button, now, it’s April Fool’s Day, in London.

That is a helluva a lot to deal with in one week! Props to you for making it out the other side!

LikeLike

Thanks — I felt like I was just getting bombarded w/messages this week. Or maybe it’s that I pay more attention at these liminal religious moments.

LikeLike

All I can say right now is that if *hugs* could travel through the internet on over to you, then this *hug* should be there by now.

LikeLike

thanks. I felt it!

LikeLike

I’ve been lurking for a while, and I’m afraid this might seem an odd post for a first comment. But it’s the sort of post that just makes me want to hug you (if you want a hug, that is).

Although it was RA who first drew me to your blog, it’s you and your writing that bring me back. I’m a chronic people-watcher, and the ones who most fascinate me have both lovely souls and surprising intellects. That, by the way, is you. (Sorry; I don’t mean to embarrass you. …And now the parentheticals are getting out of hand.)

Anyway. Thank you for letting your readers travel with you. Your journey, directly RA-related and otherwise, has inspired emotional honesty and provoked new ways of thinking for this reader. There’s something profoundly compelling about your blog. I wish I could offer something tangible to encourage you right now, but maybe it could help to know how much good you’ve done.

Bleh. I hate trying to figure out what to say to someone I’ve never properly met. I’m reminded of the numerous reactions to the “What if you saw Richard in person?” question. It’s even harder without all the nonverbal cues, so please forgive the rambling awkwardness of this comment.

Oh. I recently graduated college, and I’d like to say with all the conviction of an undergrad (take that as you will 🙂 ) — you sound like the sort of professor I most enjoyed. I wish there were more like you.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment, myster.seeker, and welcome. You don’t ever have to excuse yourself for offering someone kind words / comfort. I appreciate the virtual hug and the compliments for me and the blog.

LikeLike

What a week! sorry for your emotional upheavals. Sending happy Thoughts your way xxx

LikeLike

many thanks, bechep.

LikeLike

Maybe creativity is what helps you reshape the random data into a pattern that’s meaningful?

LikeLike

Lost, I think that’s right. I’m looking for a world in which all the pieces fit and they are never all going to fit. I just have to construct it — creatively.

LikeLike

Difficult to find a proper response to your post, Servetus. Maybe the fact that there is a response *at all* is *enough* response? All I can say is that I am wishing you well – because it seems to me that you *really* deserve it.

LikeLike

Thanks, guylty. I don’t know if there’s an answer or maybe I’ve realized i just have to decide what the answer is myself because i’m not going to get one otherwise … 🙂

LikeLike

Hugs and prayers to you. Remember you got friends in this big wide world who care about you.

LikeLike

Thanks, and hugs back. Part of why I write this all here is that I *do* know, and really appreciate, that you all care!

LikeLike

Wonderful post, Servetus – thank you for it.

A slightly different take on ‘fans’ and pattern recognition can be found in the movie ‘Silver Linings Playbook’. Robert de Niro portrays the devoted fan – and Jennifer Lawrence’s character – while consistently judged, maligned, and labelled as ‘crazy and easy’ by others – shows herself to be the ultimate master of all patterns and meaningful ’cause and effect’ of outcomes in the movie. 😉

I really loved the painfully blunt dialogue and if you have the time, I can certainly recommend it – but then, I’m a fan of David O. Russell movies, and just love that he consistently gets these movies made. 🙂

LikeLike

Will put it on the list, but have to admit that when I read the plot on imdb it reminded me in terms of shape of “As Good as it Gets,” which was a turn off.

LikeLike

Just brought it up as an alternate presentation of ‘fan behavior’, ‘pattern recognition’, and ‘meaning’, which you cover in this post via the Gibson book.

LikeLike

I would love to think that my daughter will meet a teacher like you (((Servetus))).

LikeLike

(((Joanna))) I hope your daughter meets many teachers who are better than I am!

LikeLike

[…] and their potential attraction to you as related to your own past; that process ended suddenly when you got the phone call from [Erebor]; you decided you’re abandoning or at least modifying that self-definition and trying to put […]

LikeLike

Rush therapy, Armitage tangential | Me + Richard Armitage said this on May 2, 2013 at 4:58 am |

[…] first night at my shul and the second at, following my now three-year pattern (two years ago; and last year), with Peskies at the Fuzzies’. I’ve got all the chametz out of my apartment […]

LikeLike

Status update | Me + Richard Armitage said this on April 14, 2014 at 3:49 am |

[…] The pattern I failed to recognize in this complex was that mom was already dying. The diagnosis came weeks later but she must have already known […]

LikeLike

OT: Three things I have to put down — to come back to | Me + Richard Armitage said this on April 22, 2014 at 4:45 am |

[…] found its way to me after some off-blog discussions last week. I have long been interested in systems of pattern recognition (and am starting to think that fandom may be one of them). It will appear in three parts. The normal comments policy — see sidebar — remains in […]

LikeLike

Why Richard Armitage IS Francis Dolarhyde … and you should love him anyway, part 1 [guest post by @FrauVonElmDings] | Me + Richard Armitage said this on February 9, 2015 at 1:42 am |

[…] was about the religion stuff, and that wasn’t wrong, but it was also a relief to be away from the expectation of being emotionally available. I could say a lot more about that but I will skip — my need to restrict my emotional […]

LikeLike

me + my dad, or: I’ve been trying to finish this since Father’s Day | Me + Richard Armitage said this on June 28, 2015 at 2:35 am |

[…] ones, that addressed fundamental problems or questions of mine, over and over, in ways that made me wonder what pattern I was caught up in, watching him. And these choices persist into the present, even if I have been resistant to some of them (Francis […]

LikeLike

Those are pearls that were his eyes: me + Richard Armitage sea-change? | Me + Richard Armitage said this on March 21, 2017 at 7:39 am |

[…] Hobbit — films with a main character driven to ruin by his inability to abandon a quest that was ultimately foiled for him by his own […]

LikeLike

Vanya interval | Me + Richard Armitage said this on January 17, 2020 at 7:34 pm |

[…] 8. Pattern recognition. A general problem in my life. For example. […]

LikeLike

Finneganbeginagain | Me + Richard Armitage said this on September 10, 2021 at 4:42 am |