What if I loved Hamlet the way it was? Me + the gloomy Dane + soliloquies + the audiobook + Richard Armitage

[Left: Richard Armitage “vines” To be or not to be. My cap.]

[Left: Richard Armitage “vines” To be or not to be. My cap.]

Why are we so ready to laugh at people declaiming that line?

Because there’s almost no way to say it, after four centuries — notwithstanding my enjoyment of Armitage’s uncompromising delivery and my giggle about the question mark on his forehead — that doesn’t sound a little belabored. Tedious. Seen in that light, David Hewson and A. J. Hartley’s repurposing of the Hamlet text addresses one obvious problem right off the bat: Shakespeare as chestnut. The soliloquies in particular are so well known that they can easily become trite. Writing them out — with, perhaps a textual reference here or there so that those in the know are both reminded it’s Shakespeare and flattered by their recognition of the reference — is part of their approach to trying to bring Hamlet to unfamiliar or dismissive audiences.

Upon reflection, I’m not sure who I’m writing to here — people who love Hamlet or hate it or those who are indifferent. Is this the Hamlet adaptation with “something for everyone”?

It’s always hard to reach the indifferent. But it’s easy to start out with the skeptics, because that’s part of Hartley and Hewson’s target audience.

Already hate Hamlet? Don’t like Shakespeare?

If so, you’re not alone. I ran into this problem all the time with students who’d been turned off the play in school. If they remembered and understood Hamlet, they often thought of the main character as a spoiled, vacillating twerp who can’t get over himself. Whiny. Not a figure whose questions really resonate, except perhaps among the super-emo / Goth crowd. All the action takes place in the mind and not enough of it on stage. (And, no, I’ve never encountered a student who believed that you had to be able to quote Hamlet in order to get women to give a damlet.)

I’ve heard so often what a dope Hamlet is that I’ve considered proposing that student editions of Hamlet should carry a warning label:

Warning: excessive reading of Hamlet could cause you to learn to hate Hamlet.

Hewson and Hartley have done a good job of explaining their response to this problem. Again, redressing the soliloquy has to become a primary focus. At some point in the history of theater, oratory was seen as a prized talent to be appreciated on its own terms. Apart from such opportunities a soliloquy might once have given the actor to reveal his bravura and sprezzatura, however, these days it works as a tool of characterization within a role, not a snippet to be excerpted from context. In short (as I suspect Hewson would agree), the soliloquies in Hamlet do not further the plot. According to him, swift, linear storytelling is part of what makes an audiobook “work,” which excludes monologues. He terms them “boring and predictable.” The character of young Yorick constitutes the authors’ attempt to solve this problem — and that character has turned into a particular listener favorite. Once again, problem solved.

For Hamlet haters, time for a rethink — seriously, even apart from the fact that Richard Armitage is reading the piece. Particularly if you like action, intrigue, history, and suspense, you could listen to this and get more interested in Shakespeare and indeed, in Hamlet. (Although I’d suggest the next step be the theater and not the written version — what sold me on Shakespeare more generally in high school was seeing it live.)

But what about Hamlet lovers?

But what about Hamlet lovers?

(What about me? Servetus whined.)

The reaction I hear from my students was not my high school experience with Hamlet. I write of Hamlet as a long-time defender of Hamlet. (Fabo and I were reminiscing about our personal “introductions to Shakespeare” here.) As a hyperreligious seventeen-year-old, I found (and still find) his problems and his way of speaking about them hugely compelling, practically from the moment the character opens his mouth. His first two lines in the play jibe or insult Claudius — how satisfying! And the philosophical and cognitive problems that Hamlet raises for himself and the viewer — how do I know what is true? when are people being sincere? how do I deal with hypocrisy? what is the relationship between my past and my future? who shapes my future, fate or my decisions? how can I bear the pressure of all of this? what makes me sane? and what makes me real, and different, as opposed to the customs that shape me? — appealed to me as a teen and built an important background to the kinds of issues I addressed in my research. As neither a scholar of Shakespeare or English literature, however, I am just familiar enough with the play to relish it (and teach it) in the manner we usually see it. So I’m sure it surprised no one when I confessed myself a fan of Hamlet “as is,” with all its melancholy rumination. I remember thinking maybe Mr. Armitage could do a monologue as an “added feature,” knowing that this doesn’t work precisely for the reasons stated above. I assume he had reasons for not participating in the New Zealand festival Hamlet monologue vid with so many other Hobbit actors.

After listening to this audiobook six times, I still don’t know that I’ll ever get over loving Hamlet‘s monologues. (And luckily, I’m not required to choose. It might go hard with Armitage.) That said, it’s interesting to look more closely at how rewriting what was originally an internal monologue into a dialogue between Hamlet and young Yorick affects what a scene in the play accomplishes or what impression we leave it with. We can see this difference fairly clearly at Hamlet’s entrance into the play in Act One, scene 2.

As Hewson has noted, the style of rewrite that he and Hartley chose changes what we think we know about Shakespeare. I think, however, that the changes end up being more thoroughgoing and potentially aesthetically significant than simply remaking a play that has enjoyed a centuries-long reputation for melancholy into a mystery-thriller with a rousing “story of blood” and “love and passion.”

How you feel about that — as lover or hater of Shakespeare or Hamlet — I will leave up to you. My reflections follow, in sections on my understanding of the original, my perception of what Hartley & Hewson do with the scene, and what I think Armitage provides.

Into the story

Into the story

Here’s the text of the scene à la Shakespeare — the version used in many university classrooms in the U.S. is that of the Riverside Shakespeare, but for convenience, I’ve simply chosen a modern edition like the one I read as a teenager, as my argument about the effect of this adaptation is not based on the extent of its close emulation of Shakespeare’s language. A basic introduction to the problems in establishing the text of Hamlet at wikipedia can be read here and editions of all of the texts are found here — keep in mind throughout Hartley and Hewson’s excellent point that there is no one, canonical Hamlet text, and their decision to embrace the first or “bad” quarto in terms thinking of how to shape a narrative based on “action over rumination,” discussed in their afterwords about eleven minutes before the end of the audiobook.

If you want to take a listen, I’m starting at about twenty minutes into chapter 1 of the audiobook, just after the depiction of Elsinore, as young Yorick is described observing events in the castle.

The play opens on the battlements of Elsinore. There, officers of the guard (including Barnardo, whom Armitage played at the Birmingham Rep in 1998, in his immediate post-LAMDA career) encounter a ghost whom they later recognize as Hamlet’s late father (also named Hamlet, setting up questions about individuality, identification, and fate). The spooky confrontation with the Ghost disseminates an atmosphere of unease and confusion about “what’s real” in the atmosphere of the castle. Additionally, the soldiers explain the impending vengeance of Fortinbras (whose father the late Hamlet had dispossessed) as the source of a threat of war that enhances this feeling of foreboding.

Shakespeare (my own, conventional view)

Shakespeare (my own, conventional view)

The second scene opens with the entrance of Claudius, brother of the late king and Hamlet’s uncle, with members of the court, including Gertrude, Hamlet’s recently widowed mother. Claudius explains that despite the freshness of his grief for his late brother the king, he and Gertrude have married hastily to forestall Fortinbras from thinking the court so immersed in grief that Denmark is vulnerable. The play then introduces several characters (Voltimand, ambassador to Norway, also played by Armitage in 1998; Polonius, the royal counselor; and his son, Laertes) before turning to the initial encounter between the royal couple and Hamlet, who’s just returned from his studies at Wittenberg. The discussion at this meeting sets the terms for their interactions and perceptions of each other throughout the play.

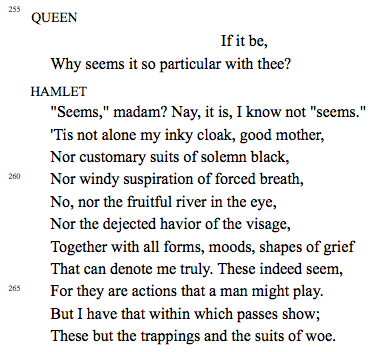

Basic commentaries note the prominence of terms for appearance in Hamlet, beginning with this scene, where “seem,” “play” (act), and “show” find themselves in the mouths of multiple characters. Hamlet’s use of pun and double entendre in each of his first three lines underlines both his suspicion of the royal pair and the feeling that nothing at court is as it appears, as every word (“kin / kind,” “son,” “common”) carries more than one meaning. By telling, or claiming to tell, the truth in such a guarded fashion, depending on how we read the scene, Hamlet either sets himself up as the truth-teller against all the other liars (how I saw it when I was in high school), or else further muddies the waters by disseminating uncertainty about when exactly his own speech should be considered unironic (a point made to me in a lecture in college) — a stance that may be either political or emotional or both.

[Source.]

[Source.]

Claudius and Gertrude’s conflict with Hamlet stems ostensibly from what they find to be an excessive display of grief on Hamlet’s part, set up against their attempt to send the world a contrasting message of strength. We see here the medieval and early modern concern with the unity of appearances and reality as well as the cracks that incipient modernity places in the perceived possibility to locate this unity. On the one hand, as historians have pointed out, the look and execution of a monarch’s ritual appearance were indistinguishable from the thing the ritual accomplished. In other words, ritual and politics were indistinguishable, which explains why the characters dispute this issue. Gertrude and Claudius can’t simply leave Hamlet alone with his feelings and Hamlet can’t accept the expedience of their marriage because, while they differ about the outcomes of a fitting display of grief, on one level, none of them see a distinction between the display of grief and the thing it is supposed to accomplish. On the other hand, however, the debate over grief raised by Hamlet’s appearance and behavior creates a transformative tension with the traditional view of display — for to us as for Shakespeare’s audience as well, the concern with grief as politics is only a pretext for other concerns. They negotiate over mourning but their transaction surrounds power. As the son of the late king and of Claudius’ new wife, Hamlet indeed occupies the position of rival, albeit a weak, disinclined one, and the new king signals his insecure awareness of this state of affairs throughout with unnecessarily forceful attempts to stomp his nephew into the ground. In this atmosphere, the discussion over how sincere Hamlet’s (vs the couple’s) grief is as a means of speaking obliquely of the still-too-dangerous rivalry, the tussle over “appearance” vs “real feeling” in Hamlet’s words reveals a (n intriguingly modern) discussion of sincerity / insincerity that some scholars might interpret as an aspect of an emerging individualism in the West. For Hamlet will maintain that he is Hamlet, his feelings his feelings, apart from the customs and practices that signal his state of mind to others.

From Hamlet’s position, either Claudius and Gertrude care (only, mostly) about how things look to the outside world, and are thus cheating their grief, their statements about political concerns notwithstanding — or, in fact, they don’t care about the late Hamlet’s death at all, so that their real behavior in not observing a decent period of mourning is in fact equally, or even more damning, than if they had simply simulated the appearance of grief. Like many grieving stepchildren, Hamlet’s got them coming and going, and in his judgment of others’ behavior, he embodies a typical late adolescent incapacity to see shades of gray, except when in dialogue with himself. Either way, the pair is lying about something — their grief, or their self-interest. In this setting, of course, no choice that Hamlet makes about how to behave (“seem”) can be taken for what it is by Claudius and Gertrude, since those who “seem” themselves are unlikely to conclude that any other party is not doing the same.

Nonetheless, in terms of the most obvious reading of the sense of his lines (below), Hamlet asserts that his grief is real — he does not “seem” to grieve, but “is” indeed grieving. The question is how the audience is supposed to take that insistence. From Gertrude and Claudius’ position, if Hamlet is not engaging in a potentially hazardous political challenge quite yet, he’s at least lighting the sparks of a power struggle with his insistence on wearing black and his hostility to the crown. (Echoes of the main theme of Antigone — statutory mourning as political revolt.) On the first point, Gertrude somewhat sententiously reminds Hamlet that everyone must die and pass into eternity. When Hamlet agrees (with a sarcastic double entendre), Gertrude presses to know what Hamlet’s problem is.

Looked at more closely, this short speech also potentially undermines what seems like a simple distinction between display and sincere sentiment, and how we take it sets the stage for our interpretations of what the characters will do later. Claudius seems clearly (both in terms of power hierarchies, and by his speech) to take the position of Hamlet’s antagonist, and all his words in the scene attempt to assert and reassert this power. But it’s not quite clear, yet, what exactly Gertrude is doing here — is she miming the role demanded by the state, pursuing her interest in allying with the new king, or genuinely concerned with what seems like excessive grief — or, although the implication is still coming from the scene, madness — from Hamlet? (The play doesn’t tell us and the actor must decide.) And although he states that what is inside of him is real, Hamlet himself spends more time here conceding that people can fake mourning by wearing black clothing, sighing, crying, looking downcast and by other means. The “trappings and the suits of woe” are incidental to his real mood, but if that’s true, they could be incidental to anyone’s real mood (“These indeed seem / For they are actions that a man might play”). He may be trying to tell the king and queen that he’s truly upset, but in fact, his words equally underline the “show” elements of grief and point to his awareness that the performative qualities of grief undermine perceptions of sincerity.

(Short interjection: “But I have that within which passeth show” is one of my favorite lines from all of Shakespeare’s plays.)

Hamlet’s confession (and perhaps the way that it points to the potential he carries for deception) provokes Claudius to become even more unsubtle and patronizing in his criticism of Hamlet. The new king now bursts out with all the reasons that Hamlet should leave off: the extent of his immoderate grief, intended to honor his father, is a self-contradictory sign of filial impiety; un-Christian (the pagan quality of immoderate grief was a common topos of Protestant funeral sermons of the period); unmanly; a sign of weakness or instability (dig — Hamlet is potentially too erratic to govern); and a rejection of the course of nature. If this attitude is truly real on your part, Claudius seems to be saying, then get over it already. The end of Claudius’ speech, which proclaims Hamlet his successor and invites him warmly to be at home in the Danish court, reads as disingenuous given its gaslighting beginning — stay here, think of me as a father (and let me keep an eye on you). Hamlet quietly (or sullenly?) agrees to follow his mother’s wishes, but not Claudius’; and Claudius’ proposal of an extravagant toast to celebrate Hamlet’s agreement seems gauged to offend even further the young man already disquieted by the celebrations. With his refusal to confront Claudius again, and his hangdog response to his mother, Hamlet ends this portion of the scene having embraced precisely the level of insincerity in his dealings with the pair that he criticized in their execution of mourning for his father.

Self-disgust is the result — rage against the self. Here the soliloquy begins.

After he expostulates against his own flesh (the matter of what “solid” means is disputed, as different editions of the play also printed the adjectives “sallied” and modern editors have postulated that Hamlet was meant to have said “sullied,” so that he mourns alternatively his own materiality, the burden of wounds under which he is suffering, or a soiled feeling derived from his mother’s remarriage), the themes of the soliloquy, in order, include Hamlet’s desire to end his life in contradiction to the demands of religion; the inherent decadence of the world; his disgust with his mother’s quick resort to Claudius, a man clearly inferior both in power and in kindness to his own father; Gertrude’s hypocrisy and by extension, that of womankind; his own inferiority to his father; the fact of the “incestuous” quality of their marriage (for more on this, see my discussion of the forbidden degrees in canon law in Richard III’s life; we’ll come back to this when talking about the audiobook) — and finally, his own necessary silence over the topic, his need to keep silent even as his heart breaks to speak. Gertrude’s hypocrisy and his anger at her, the subject of the preponderance of the monologue, in turn give rise to his own feelings of suffering in a decaying world and his anger at himself.

This isn’t my favorite of the soliloquies, but it’s still worth asking what impression we have of Hamlet and Hamlet before and after this point. In what context do we take this speech as the index of self-revelation as which it was intended? As I’ve suggested, the play seems heavily concerned with the question of reality vs appearance and sincerity vs hypocrisy, with Hamlet either as the representative of reality and sincerity, or else someone who contributes to the audience’s problems in grasping which points of the story are real and which are deceptive.

What the soliloquy adds to this mix is a decisive third element, one that one would have been very much on the minds of the play’s original audiences: that of the ailment that early moderns called melancholy. Is Hamlet mentally ill — and in what degree? By broaching the topic of his weariness with his own body and his regret that religion forbids him from harming himself, he moves himself into the realm of what we today might call depression. Again, part of the problem lies in how the actor plays the scene and what the observer understands as the proper show of grief — but this isn’t tumblrspeak, where we talk about Richard Armitage having ruined our lives. Despite the possibility that Hamlet could be exaggerating for effect, still the audience who doesn’t yet fully know the character cannot take a threat of self-harm as an ironic assertion. To be so disgusted by one’s mother’s behavior that one wants to end one’s life might be seen as a disproportionate reaction from the audience’s point of view as well (not just Claudius and Gertrude’s).

If audience members perceived that to be the case, they might have moved beyond a diagnosis of melancholy, to one of madness (which was thought to be characterized inter alia by inappropriate or exaggerated reactions on the part of the sufferer). And if we think Hamlet mad now, how much more so will we do when we observe him responding to his other interlocutors in the play, especially Gertrude, Ophelia, Laertes? Or, in the same vein, if we do believe him to be speaking sincerely, here, and not making show or speaking rhetorically against the quasi-political accusations of Claudius, to what extent does Hamlet truly understand his own situation as speaker? In short, what the soliloquy does is potentially underline whichever reading of the scene that the viewer is inclined to have taken as the “right” thread from the first half (that Hamlet is legitimately overburdened with sadness; that he is acting out mourning as a criticism of his parents) and then draw that reading into question by pointing out that Hamlet may be either mad or himself hypocritical. The soliloquy adds power to whichever reading we take away from the beginning of the scene, but it also simultaneously decenters our earlier perceptions.

The scene ends with Horatio’s condolences and commiseration with Hamlet over the speed of the wedding, and his revelation that he and others have seen his father’s ghost, walking upon the castle battlements. And Hamlet ends the scene by declaring that he will speak to the apparition, though “hell itself should gape / And bid me hold my peace.”despite the many cloaks of appearance all around him, the truth will out:

Note that “doubt” here means something like “suspect” — if his father’s ghost’s abroad, something’s fishy. Nonetheless, reality (“foul deeds”) will not be able to survive all the earthly attempts to maintain appearances. Another edgy speech — in that Hamlet asks for darkness (“the night”) to reveal all, rather than the light.

Note that “doubt” here means something like “suspect” — if his father’s ghost’s abroad, something’s fishy. Nonetheless, reality (“foul deeds”) will not be able to survive all the earthly attempts to maintain appearances. Another edgy speech — in that Hamlet asks for darkness (“the night”) to reveal all, rather than the light.

What we have set up here, then, is a potent mix of confusion about reality, power struggles that cannot be articulated fully, the bereaved child grieving, perhaps obstinately, for his father. What the soliloquy accomplishes here is to add the factor of a good faith or a deceptive articulation of Hamlet’s interior state (which may or may not be influenced by his melancholy — even if Hamlet is telling the truth about himself from his standpoint, it may not be the whole story). Even as the scene sets up the action of the play, it keeps numerous readings as to how we should understand that action open.

This is approaching 4,000 words so it’s time to stop for tonight. Next — how Hartley and Hewson address the same scene.

Serv, don’t slap me but I just remembered why I hate Hamlet. 4,000…YOU go girl!

LikeLike

hmmm. 🙂

LikeLike

This makes me want to revisit Hamlet (it’s been a decade and half or more). The fact that Hamlet is actually appealing to me now more than I was a teen is a bit disconcerting tho…. Thanks for this and I look forward to the rest.

LikeLike

I don’t think it’s really a play for teenagers, although there’s a chunk of it that teenagers may be inclined to like. I’m glad if it was helpful. The rest when my drive is over.

LikeLike

You did say it wasn’t really for teenagers, I just remembered wrong. I find navigating the politics of daily life (who to believe, when to believe them, etc) tiring. Life is tough enough and adding that to the mix… Hope the driving is going well!

LikeLike

it’s a totally human dilemma even if your late father was not the king of Denmark 🙂

almost done. home tonight.

LikeLike

It does inspire me to return to the text/poetry as well. Not my favourite of the plays (whoever penned them! – I wrote an earnest and determined essay in senior high school insisting Christopher Marlowe was “Shakespeare”! Please don’t laugh too hard at me. I think it was just a seventeenth- yr-old’s, way of exploring through dumb argument?

) No matter, I am thoroughly tired of the Oedipus complex interpretations, and “melancholy Dane” – this has prompted a re-visit. Thank you, Servetus. 🙂

LikeLike

the argument that WS didn’t write the plays (or that there was no WS) is very popular these days 🙂

I didn’t talk about the Oedipus interpretation because it’s so thoroughly anachronistic. I think it helped me in college to see a production of the play where the viewer was put in the dilemma of whether Hamlet was mad or just an incredible conniver, i.e., one that didn’t really let us consider the possibility that he was sincere. Since then I’ve been more open to this kind of reading.

LikeLike

Indeed. It is “old-hat”. And analysed to death. I do have to return to the text, and ignore that many phrases have become, not just part of our collective cultural memory, but descended into parody. “Alas, poor Yorick.” “There are more things, Horatio”… etc.

I remain intrigued by the Shakespeare as the author question. Please don’t laugh too heartily at my seventeen year old self. It had more to do with ego, and ego challenging received wisdom, than with acumen.

It is not relevant to the beauty and timelessness of Shakespeare, but I do have a couple of books on the shelf, “Contested Will”, and “Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton”. Because I love mysteries – but even at 17, I was silently telling Hamlet: “Just grow up, and sort yourself out!” 🙂

A few (indeed) decades later, I just have to return and re-capture the awe and long love of Shakespeare. And plan for a 300 km trip to Stratford, Ontario, summer festival, and bask in whatever play, whatever interpretation…..

LikeLike

Who hasn’t laughed at Carole Lombard and Jack Benny in that old film?

As one who has loved Hamlet for a long time, studied the play and come back to it every five years or so, seen most filmed versions, and even played the Dane in selected scenes for a drama class, I thank you for this.

I look forward to your next installment.

LikeLike

[…] now, some historians think that social disciplining works as a response or corrective to the emergence of individualism unleashed by the Renaissance and Reformation. (And that hypothesis would work well with Boyer and Nissenbaum’s diagnosis that the victims […]

LikeLike

“we will burn, we will burn together” or: Re-reading The Crucible now – as promised, the “witch cake” | Me + Richard Armitage said this on June 12, 2014 at 5:58 am |

[…] — with candids of it appearing nightly. Then again, will ever I write the second part of my Hamlet analysis? (Doubtful, if I don’t relisten to it.) Will I get back to the position of Guy of Gisborne in […]

LikeLike

Time to write some actual prose about Richard Armitage, I think | Me + Richard Armitage said this on July 8, 2014 at 5:56 am |

[…] I do think it should be something special, the best of the best, and this play wasn’t that. I am a Hamlet lover, even if it’s not my favorite Shakespeare play, and I’ve been more drawn into it in the […]

LikeLike

Fardels bear[ing], or Richard Armitage as Hamlet? | Me + Richard Armitage said this on March 10, 2018 at 8:58 am |