Toward a review of Richard Armitage as John Proctor in The Crucible

This title has a bit of an elegiac sound, admittedly, but I’m not even close to done posting about Richard Armitage and The Crucible. I just wanted to delay the next chronological post because Thursday, August 28th was a rough day and I am not sure I want to relive it, even in writing, just yet. (I promise I will, though.)

Also, I read another post today that suggested that a fangirl can’t be an objective observer of a production. Sigh.

Yes, fangirls have a stance in-between. But, actually, I can observe everything in detail and have an incredibly transformative reaction to something, and still relativize my own observations and put my emotions in context! That’s what intellect does for a fangirl. And you know: who better to review an actor’s performance than someone who’s spent four and a half years watching that actor’s every performative move? I admit I don’t have a full context for this performance in the culture of the British stage, or in the history of portrayals of John Proctor (which would undoubtedly be a lengthy discussion), but I do have a lot of other contexts and equipment available to me. So here’s a shot at a real review of Richard Armitage and his performance in The Crucible, as directed by Yael Farber — keeping in mind that I saw performances two weeks before the end of the run. Eventually a review of the play itself will follow.

***

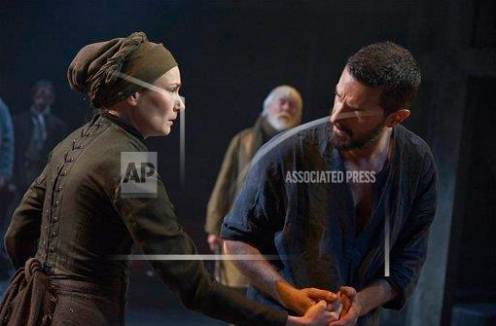

John Proctor (Richard Armitage) and Elizabeth Proctor (Anna Madeley) touch as they must separate before her arrest, in Act Two of The Crucible. Source: API Images

John Proctor (Richard Armitage) and Elizabeth Proctor (Anna Madeley) touch as they must separate before her arrest, in Act Two of The Crucible. Source: API Images

***

Richard Armitage as John Proctor — something that made me happy for him professionally, but left me ambivalent intellectually. It will be uncontested that Armitage’s portrayal of Proctor represents a turning point in his career, not simply in terms of the bottom line, although he’s proven that while headlining a solid, even remarkable, production of a respected play, he can sell out a large theater by appealing not just to his fan base but to critics and theatergoers as well. It’s also a turning point artistically for him, in terms of the way that the role expands the range of his repertoire up until now, adding something new by giving him his first serious leading role in live theater since his student days. For those who witnessed it, Armitage’s Proctor — ephemeral as it was, even with a preservation of important aspects of it on video — is now the character, the performance that impresses upon us Armitage’s benchmark as an actor: how far he has come; what he has mastered; what he has yet to learn; and who he might become in the future.

[Right: Richard Armitage as John Prctor in Act One of The Crucible. Source on watermark]

[Right: Richard Armitage as John Prctor in Act One of The Crucible. Source on watermark]

For those familiar with it already, Armitage’s work in The Crucible shows itself in strong continuity with that of many of his previous roles. His capacity to use his body expressively to convey moods and feelings, for instance, is as equally and fully on display as in his early, expressive roles in North & South (2004) and Robin Hood (2006-8). These roles often relied heavily on the embedding of pregnant details and quickly shifting microexpressions, in which closeup views of Armitage’s face were particularly important, a style that reached its summit in his portrayal of Thorin Oakenshield in the first two Hobbit films (2012-13). While those elements of his habitus persist, in Proctor, conditioned by the necessities of the stage, Armitage shifts his expressive energies to his stance; the positions of his head, neck, and shoulders; and particularly to his hands, which are used repeatedly and extensively both to express his own state of mind and to reflect or symbolize his relationship to other characters in the piece. While he certainly repeats some pieces of his familiar gestural canon, these are mostly repurposed and modified so that I at least was not constantly reminded of previous characters. In particular, Armitage’s ability to manipulate his size to negotiate Proctor’s different status conflicts in the play seems enhanced over against previous roles, and he seems more comfortable taking not only low status positions that involve head moves, which he has always done movingly, but also those that involve repositioning his body in a crouch, which he does more effectively here than he was able to achieve while playing John Porter in Strike Back (2010) several years ago.

[Left: Abigail Williams (Samantha Colley) confronts Proctor (Richard Armitage) in Act One of The Crucible. Photo by Johan Persson]

[Left: Abigail Williams (Samantha Colley) confronts Proctor (Richard Armitage) in Act One of The Crucible. Photo by Johan Persson]

Early viewers of Armitage’s work fell for Mr. Thornton’s attraction and love for Margaret in North & South, and this play, too, incorporates a searingly effective kiss. The pent up quality of Proctor’s sexual energy comes to the fore primarily in the simultaneous attraction and repulsion that he displays toward Abigail (Samantha Colley), as when he cycles through moments of lust, horror, regret and self-disgust while responding to her overtures — though it reappears as well in his frustrated attempt to kiss a response from his wife, Elizabeth (Anna Madeley), in Act Two. But all in all, the typically predominant note of tenderness of Armitage’s portrayal of intimate relationships is enhanced here from his earlier work, as we witness longer interactions between Proctor and Elizabeth, in which severe conflicts with both verbal and physical elements are resolved only gradually, drawing out the dramatic tension and enhancing the pleasure of its resolution. Where Thornton smoldered over long seconds, Proctor has to do so over minutes — with no mitigation in the intensity of his energy. Armitage’s capacity to reveal a surprising emotional vulnerability in such a conventionally masculine character as Proctor finds its clearest expression in the moments of Proctor’s anguish, particularly in Acts Two and Four. It was astounding to me to see the gradual transformation by which the self-confident, at times even menacing, physical presence of Proctor in Act One was reduced to body-wrenching sobs by the events of Act Two; I would not have otherwise credited that Proctor was a sloppy crier, but it works tremendously well here.

[Right: Proctor (Richard Armitage) admonishes Abigail (Samantha Colley) not to speak ill of his wife, in Act One of The Crucible. Photo by Geraint Lewis]

[Right: Proctor (Richard Armitage) admonishes Abigail (Samantha Colley) not to speak ill of his wife, in Act One of The Crucible. Photo by Geraint Lewis]

Thus, in The Crucible, Armitage as Proctor showed himself the consummate master of his own physical expression and corporeal presence. Seen live, the charismatic energy that flows off of the actor, which most of us have only glimpsed on screen as a magnetism that prevents us from looking away, is unmediated and at times shocking — whether it proceeds from his eyes, his furrowed forehead, or from his muscles. This production necessarily makes more obvious use of his movements, and in this quality lies the true and, I think, largely incontestable triumph of Armitage’s work this summer. He displays the stamina to complete a physically energetic performance, the fine feeling for subtlety, a sense for the expressive physical outcome of an emotional detail, and above all an ability to combine these effectively that serve him not only in good stead, but allow his Proctor to add an emotional depth to this character that fairly lifts him off from Miller’s somewhat self-righteous pages. It is above all Proctor’s moods that make the twists and turns of Act Two’s negotiation between the farmer and his wife fully comprehensible — as we see through the physical posture of Proctor’s defensiveness that one contributing reason the bewitchment craze goes so far in Salem is that Proctor is simply unable to credit his wife’s worries about Abigail as stemming from anything beyond marital jealousy. This is not a reading that lies obviously to hand in the play — but Armitage’s Proctor, who tries to ward off his wife’s reproaches, simply cannot see straight through the political maze that his adultery has placed him in.

Moreover, Armitage’s physicality has a simple, but striking, effect on the characters around him. When agitating actively, he is able to convey a menacing stillness or an off-balance motion that unsettle the characters around him with equal skill. More importantly, particularly in Act Three, he often provides a glowering presence in the background, so that his reactions often contribute as much to the mood of a moment as do his actions. This energy benefits the ensemble of the play, into which Armitage fits seamlessly and cooperatively; this was not a play that suffered at all from the “guest conductor” or “star vehicle” problem of lack of cooperation between the different levels of characters. Armitage is a modest headliner who never takes up more space on stage than is appropriate to his character — and sometimes takes up less. We have a lot of opportunity to observe the strengths of the rest of the cast because Armitage uses his physicality cooperatively — an attitude that seems particularly necessary in his interactions with Abigail, the officers of the court, and the various people he is required to catch or restrain throughout the play.

[Left: Richard Armitage in rehearsal for The Crucible. Photo by Johan Persson]

[Left: Richard Armitage in rehearsal for The Crucible. Photo by Johan Persson]

As a long term watcher of this particular actor, however, it is hard for me to avoid the suspicion that one reason this all worked out so well was that The Crucible was a particularly good play for Armitage’s first theater outing as a main lead, because many of Proctor’s characteristics fit tremendously well with Armitage’s gifts. [ETA: I am not saying here, by the way, that Armitage’s primary virtue in this play lies in having chosen the role well, although I do think that this has been a pattern in his career.] Armitage’s qualities as an everyman and the muted quality of any cerebral vibe he sends off fit Proctor tremendously well, for instance. And the reviewers are spot on who note that Armitage’s physicality and presence suit amazingly, and bring something new to, the notion of Proctor as honest farmer caught up in a political situation he somewhat understands but definitely cannot control, as opposed to the political or ethical theorist or intentional rebel or outsider as which he is often played. Armitage’s particular gifts make his Proctor unique. With his big body, his intense presence, his large eyes, and his ability to look wounded and confused and underlay those states of mind with a million nuances, on top of his amazing stamina and concentration, Armitage is the perfect actor to play the physical and emotional aspects of Proctor. Still, the character does have an important verbal level (laying aside the problem of whether we find the way Miller puts these speeches in the character’s mouth credible or not, for performers of the play are not allowed to make cuts), and I occasionally found myself questioning, or less convinced by, Armitage’s performance in that sense. I fully credit, as Armitage has often said, that he loves literature and language and that these things pushed him away from musicals as a young man and toward classical theater. But it occasionally feels as if he does not take the language of this play seriously enough — and this is hard for me to write, for I find the language of this play largely maladapted to the gravity of its subject matter and at times so obviously anachronistic as to be ridiculous. I thus find myself in a bit of a bind as a reviewer — precisely because the emotional and physical qualities of Armitage’s performance did a great deal for me in making me dislike the play less. But there are points at which he appears to be under-committed to the verbal level of the work.

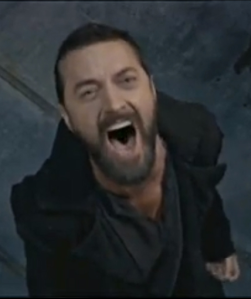

[Right: John Proctor shouts the death of G-d in Act Three of The Crucible. Screencap from Old Vic trailer]

[Right: John Proctor shouts the death of G-d in Act Three of The Crucible. Screencap from Old Vic trailer]

The matter is not thoroughgoing and if the play ended after Act Two, I suspect we would hardly notice it. But it seems to me that there are two levels at issue with Armitage’s verbal work in The Crucible. The first is technical — something about the way that Armitage portrays extreme emotionality occasionally interferes with his diction. It’s not that he’s not trying — those who sit close to the stage see the remarkable level of enunciation not just Armitage, but all the actors, achieve. (Keyword: spit.) But it’s often the case that when Armitage is at his most emotional, the pitch or timbre of his voice simply prevent us from hearing consonants and word distinctions especially well. (He may also be speaking too quickly, but indistinctness is the more obvious matter.) There’s no problem with clarity during his performance of icy anger, as in his tussles with Parris over salary in Act One — but in Act Three, from the point when Proctor is finally forced to accuse himself of adultery, his sobbing tone, which Armitage projects through his upper sinuses, meant that I sometimes could not understand what he was saying. This problem is exacerbated by the shouting of many lines — and there is a lot of shouting in Act Three (and quite a bit in Act Four as well).

[Left: Before the background of the bewitched girls, Proctor accuses himself of adultery, in Act Three of The Crucible. Photo by Johan Persson]

[Left: Before the background of the bewitched girls, Proctor accuses himself of adultery, in Act Three of The Crucible. Photo by Johan Persson]

The matter of shouting as a vocal style or rhetorical technique raises the second question, which was noted by various observers all the way through the run, and with which I find myself in agreement. Whether as a consequence of Armitage’s work, or the state of mind he creates for Proctor — there is a sense in which Proctor’s heightened anguish and fear and disturbance after the middle of Act Three (his emotional meter is always off the scale by that point) — means that sometimes there’s a combination of emotional monotony, rushed delivery, and a verbal indistinctness to his enunciation of the more important lines of the play, particularly those toward the end of Act Three, in which Proctor denies G-d, accuses the girls of fraud, and paints himself and Danforth with the same brush. The information he delivers here is not immaterial to understanding his state of mind and the reasons why the character will insist on acting as an accomplice to his own execution at the end of Act Four, so it needs to be clear: Proctor thinks he is a hypocrite — and he realizes that his own fear and arrogance have caused the state of affairs that will lead to his destruction. Armitage overcomes this problem by communicating with his not inconsiderable sheer physical emotion, so that we remain moved by his predicament as we watch him dragged off the stage — but sometimes the content of the words is more important than Armitage seems to make it, particularly in Act Three. Note that I am not saying he shouts too much: but rather that he does not shout well, or perhaps, that the way he shouts is more effective for the action level of movies where it’s often stage directions or pure reaction that are being conveyed, than for the content of this play, in which we need to know exactly why Proctor feels as he does.

The second place where I sensed room for growth in Armitage’s work is the flip side of one his strengths: his ensemble playing. Armitage has repeatedly stated that he prefers ensemble work and he thinks the level of an actor’s work is substantially raised by the actors around him. In that sense, too, The Crucible was a good choice for him because although Proctor’s clearly the lead, he has important exchanges with every other major character, and so the efforts of Anna Madeley, Samantha Colley, Adrian Schiller (Reverend Hale), Natalie Gavin (Mary Warren — whose work is so rarely noted in reviews, and which I found amazing), and Jack Ellis (Danforth) in particular are important to this play’s success. No one can be a weak link, and no one is. That means, however, at times when the play needs a jolt of energy (and I would say I observed this at least four times while watching the play — a lengthy, wordy play that operates at such a high level of tension as it does in this production in particular is always skirting the problem of tension fatigue in the audience), it is not entirely clear who is responsible for changing the dynamic. Armitage is an excellent ensemble player and this is a strong ensemble play; at the same time, with one exception, I never saw Armitage step in to try to steer what was happening in any scene. I saw Jack Ellis (Danforth) do it more often, even if I sometimes felt that Ellis was bored or phoning it in and was thus as much causing moments to drag as redeeming them. This sort of active control of a scene is something that we expect from the man whose name is in the lights, and I did not see it (or did not see it consistently) from Armitage here. As an actor, he fairly radiates energy; now, he needs to channel it more effectively toward motivating his fellow players.

The second place where I sensed room for growth in Armitage’s work is the flip side of one his strengths: his ensemble playing. Armitage has repeatedly stated that he prefers ensemble work and he thinks the level of an actor’s work is substantially raised by the actors around him. In that sense, too, The Crucible was a good choice for him because although Proctor’s clearly the lead, he has important exchanges with every other major character, and so the efforts of Anna Madeley, Samantha Colley, Adrian Schiller (Reverend Hale), Natalie Gavin (Mary Warren — whose work is so rarely noted in reviews, and which I found amazing), and Jack Ellis (Danforth) in particular are important to this play’s success. No one can be a weak link, and no one is. That means, however, at times when the play needs a jolt of energy (and I would say I observed this at least four times while watching the play — a lengthy, wordy play that operates at such a high level of tension as it does in this production in particular is always skirting the problem of tension fatigue in the audience), it is not entirely clear who is responsible for changing the dynamic. Armitage is an excellent ensemble player and this is a strong ensemble play; at the same time, with one exception, I never saw Armitage step in to try to steer what was happening in any scene. I saw Jack Ellis (Danforth) do it more often, even if I sometimes felt that Ellis was bored or phoning it in and was thus as much causing moments to drag as redeeming them. This sort of active control of a scene is something that we expect from the man whose name is in the lights, and I did not see it (or did not see it consistently) from Armitage here. As an actor, he fairly radiates energy; now, he needs to channel it more effectively toward motivating his fellow players.

(Parenthetical aside: So you see — a fangirl can be realistic about and critical of her crush’s performance. Yes, I loved Armitage in this play and seeing him in it changed my life, but no, he wasn’t perfect. And I don’t think he thinks his performance is perfect, either, given what we know about him.)

[Left: Richard Armitage, publicity photo, June 2014, by Leftiris Pitarakis]

[Left: Richard Armitage, publicity photo, June 2014, by Leftiris Pitarakis]

So again, we ask, quo vadis, Armitage? What will this performance make of him?

A final sense in which I think this play was well suited to Armitage was that in general, I have found that Armitage tends not to exude the embodied cultural capital valued by traditional theater and its audiences. This is an observation, not a criticism, because I don’t know if he doesn’t know that he doesn’t do it, or doesn’t care, or explicitly tries not to based on his ethical stance about bullshit / pretense (which I find hugely sympathetic). But whatever the reason, it makes him appear differently than the men who currently seem to be headlining traditional British theater, and it’s a bit odd as a stance for a would-be Shakespearean actor, as we know he has the stuff for Shakespeare. And while this performance was stunning and memorable and presents a huge leap not only in nuance but also in stamina and concentration over against earlier performances, the role itself, let alone the way that Armitage played it, is unlikely to contribute to enhance that impression of insubstantial cultural capital. I think this performance will get him more roles, and not only for his selling power but also for the dramatic power and magnetic charisma of his performance, an effect that even the reviews that were less enthusiastic about the play tended to acknowledge. But I think the initial offers will tend to be roles that are neither cerebral nor heavily verbal. Rather, they will be more like Proctor: big, archetypal, epic, hero / anti-hero roles that step just slightly outside the elevated canon of traditional classical theater. I also think he’s demonstrated with this that his praxis as an actor is not especially well consistent with the edginess of experimental theater (no matter his attractions to it).

With The Crucible, Armitage has demonstrated that he’s a big man for the big role. On any scale of criteria that we use to measure acting — things like the credibility of playing, his capacity to surprise and enchant even as his work stays grounded in psychological realism, his ability to play the entire range from vulnerability to bravado, his reactivity, and his expressive use of his instrument — Armitage has provided a performance that should remain memorable not only for fans, but for more general theater audiences as well.

What an outstanding review. Agree with your impressions 100%. I would love to write a review with such elegance and clarity. Wow!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the kind words.

LikeLike

I’m very interested in watching the video performance. The shouting. I’ve heard so much about all the shouting. I have my doubts as to whether the level of shouting will jangle me enough to be thrown out of the trance of the story.

This was a terrifically insightful and descriptive review of his performance.

I don’t think you can be counted as just a gushing fangirl. Not in the least.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s hard to talk about this now b/c the reviewers were so flat in their discussion of this. It’s a play that probably requires a lot of shouting and by halfway through Act Three, everyone in that courtroom is incredibly angry. I don’t think the shouting is misplaced, nor did I ever go home thinking, gosh, they shouted too much, or the play was ruined by shouting. Proctor is not the only character who shouts, so to me the kind of critique that says the shouting is ineffective b/c there’s so much of it misses the point a little. That said, if you can’t hear what’s said it’s a problem. I think here my friends who were concerned about his diction had a point, because Jack Ellis (Danforth) is much more skilled at this. Then again, he’s had way more practice at it, if you look at his list of credits.

And thanks. I try.

LikeLiked by 1 person

re: lack of objectivity, I think I realized yesterday part of what the problem is — if you are too positive, you get dinged for being partial; but if you’re not positive enough, you’re always at risk of getting dinged from a fellow fan who draws your honor into question. Hard bridge to walk across as a writer.

LikeLike

Yep, I can see that as a conundrum. Just as long as genuine enthusing for perceived brilliant performances is always allowed. 😉

LikeLike

I think seeing the positive is always better than mean-spirited picking away at the negative, even if the positive sometimes glosses over the negative. I don’t think there’s anything wrong, in a situation like this, with seeing someone with love and grace, and that love and grace can also be extended to description of the “less than perfect.” It might be different if I were his vocal coach or his director or his agent, but I’m not, and so if I describe what I see with candor, then not prescriptively, because I’m not in a position to judge on that basis.

LikeLike

[…] deflected her admonition via escape into a discussion of how she still suspects him (this is the interpretive point that Armitage added for me, which I referred to here — that Proctor can’t grasp what’s going on around him […]

LikeLike

Fracturing face: Difficult lines, lines that move, Richard Armitage | Me + Richard Armitage said this on September 12, 2014 at 11:04 pm |

I’ve loved reading all these posts, for the memories they are returning to me. In the performance I saw, I had no problem with the shouting or the diction. Actually no, I admit that at the start of the first Act, I did struggle to hear every word Richard spoke – but this happened now and again with most of the cast and I have put that down to where they were standing in relation to where I was sitting. Or frankly, because the collar of Proctors coat was sitting up so much that it nearly acted like a kind of wind-break and stopped the words from fully reaching the audience! But from half-way through the first Act, I heard every word whether it was quietly spoken or shouted.

LikeLike

There are always acoustic problems in the theater (it’s surprising there aren’t more of them), and the issues with Armitage’s voice in specific were either not as bad as I’d been led to believe or had been mostly addressed by the time I saw it. I stand by this, though — the verbal aspect of his performance was the weakest.

I’ve been misunderstood somewhere as having said this will always be the case, or that it is some fundamental general flaw in his acting, which is not what I was saying. I was saying in this production there were issues with his voice that interfered with his delivery (although I would not say hoarseness, which was frequently referred to, was the problem. I didn’t find him hoarse in performance, or at least not unintentionally so. There are moments where he’s purposefully speaking hoarsely).

LikeLike

Thank you for a thoughtful review touching upon issues about “voice” and characterization that I was wondering about from others’ comments–my being someone who didn’t get a chance to see the play. I can’t wait to see Richard Armitage’s portrayal of John Proctor via the dvd or in a cinema!

LikeLike

I’m thinking that for various reasons, this is not going to be an issue with the video, mostly because I assume they miked well for the performance and they can correct (noise reduction, etc.) in their final version.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Let’s hope so. Lavalier mics on actors are a godsend for those like me who are a teensy bit hard of hearing. ;->

LikeLike

I don’t know how they could have used them in this performance, frankly — the actors move so violently that they would have added a lot of noise. But I’m assuming Digital Theatre does this a lot, so they have solutions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] repeatedly in the past that humiliation is one of his most convincing modes. (Another reason that John Proctor was such a perfect choice of role for Armitage, for the status loss Proctor undergoes in this piece is extreme even as he claws against it at […]

LikeLike

Virile Armitage, or: richard armitage + samantha colley + anna madeley in The Crucible, part 2 | Me + Richard Armitage said this on November 3, 2014 at 5:47 am |

[…] had discussions before about the sorts of roles that are perfect for Richard Armitage (as in the case of John Proctor), and it’s hard to escape the notion that with Thorin Oakenshield we are yet again confronted […]

LikeLike

[Spoilers!] What I would have said last night about The Battle of the Five Armies, if it hadn’t been two a.m. | Me + Richard Armitage said this on December 18, 2014 at 5:58 am |

[…] but perfected versions of them. However I feel about some aspects of his performance (as I noted in my September review of his performance, he sometimes appears verbally undercommitted in the “louder” scenes of the work, and […]

LikeLike

A less than peaceful Sabbath with The Crucible on screen and Richard Armitage | Me + Richard Armitage said this on February 28, 2015 at 6:00 am |

[…] a general review of Richard Armitage’s performance in the play. Here’s a general review of Adrian Schiller’s performance in the play. Here are posts […]

LikeLike

Nipple, nipple, nipple! I’ve been informed that I’m not taking The Crucible on screen seriously enough | Me + Richard Armitage said this on March 21, 2015 at 7:13 pm |

[…] mixed feelings). All of the posts — the biographical ones, the psychological ones, the analytical ones, the fanciful ones, the joking ones, the sexy ones, the hypothetical ones, the speculative […]

LikeLike

Reading Richard Armitage, or, Assumptions I have made | Me + Richard Armitage said this on July 6, 2015 at 4:40 am |