Virile Armitage, or: richard armitage + samantha colley + anna madeley in The Crucible, part 1

[It took me forever to write this because every time I sat down to write, I got distracted by my fantasies. Cough. Drat you, Richard Armitage. You interfere with your own analysis!]

How could I write about any of Richard Armitage’s roles and not eventually talk about the chemistry aspect? I’m surprised it took me this long. In this post, when I say chemistry, I’m referring generally to the energy of attraction or rapport generated between two actors as a part of creating their characters, and at times specifically to sexual chemistry, or the appearance of sexual attraction and energy between them. A lot of both kinds was on display in The Crucible, between John Proctor (Richard Armitage) and his spurned servant-girl, Abigail Williams (Samantha Colley) and between him and his wife, Elizabeth (Anna Madeley). The stage fairly crackled in some of those scenes!

[Left: Laila Rouass as the oft-maligned Maya Lahan, from Spooks 9. Source: wikipedia]

[Left: Laila Rouass as the oft-maligned Maya Lahan, from Spooks 9. Source: wikipedia]

Evaluating chemistry from the audience member’s perspective is complicated. How we see chemistry certainly involves our personal preferences and whether the actors conform to these. But we must also take into account the skills of the actors involved (and somewhat less, the degree of their personal affinity, for talented actors should be able to produce chemistry no matter their own feelings), as well as the history and relationship between characters they are playing, and particularly strongly in the case of The Crucible, the context in which their stories take place — because sexual attraction is a culturally conditioned phenomenon whose signs are different in different historical and cultural settings. A convincing New England Puritan doesn’t show his attraction in the same way as Lucas North might. I mention this mainly because Armitage’s chemistry with co-stars has been a dicey issue for us in the past. It’s been my impression that if we didn’t like the character his character was involved with, we have often tarred the actor opposite him with the brush of “no chemistry” — even when, as frequently in the scripts he’s had, the character itself was supposed to be either ambivalent about Armitage’s character or playing games. The most notorious case of this was Genevieve O’Reilly (her admittedly lousy U.S. accent notwithstanding), who got what was in my opinion a lot of unnecessary criticism from us, as Sarah Caulfield was supposed to be playing bait-and-switch with Lucas North. Laila Rouass, whose Maya Lahan was always uncertain about John Bateman’s reappearance, got a comparatively minor shower of the same thing, and even Lucy Griffiths got her share of criticism for what was Marian’s behavior, not her own poor work. The actresses who haven’t gotten this treatment from us tend to be those whose characters comply with our desires for Armitage’s character (Daniela Denby-Ashe as Margaret in North & South; Paloma Baeza as Elizaveta in Spooks 7, who have both been fan favorites independently of our assessment of the quality of their work).

In other words — if we see The Crucible and think Elizabeth Proctor is cold or abrupt — that is because Anna Madeley is playing the character as written (as Elizabeth herself admits in Act Four when she says that she kept a cold house). The challenge, as billiepops noted a few weeks ago, lies in playing intimacy in a relationship where the partners are now partially estranged.

So — having noted the potentially complex aspects of our perception of chemistry — now I’ll move on to Armitage’s production of a sexual vibe for John Proctor and his chemistry with his female counterparts.

Sexy Proctor? The virile Puritan farmer

I admit that it starts for me with aspects of the Proctor costume — especially the boots (at right) and the coat and the beard. These symbols all trip certain synapses in the Servetus brain. But as with many roles that Armitage has played, it’s not so much the signs per se, but the way that Armitage wears and uses them.

I admit that it starts for me with aspects of the Proctor costume — especially the boots (at right) and the coat and the beard. These symbols all trip certain synapses in the Servetus brain. But as with many roles that Armitage has played, it’s not so much the signs per se, but the way that Armitage wears and uses them.

The core of Proctor’s sexuality as Armitage plays the character stems from his virility. Note the etymology of that word from vir (Lat. man, and the related term virtue from Lat. virtus, the quality of manliness, bravery, and moral excellence, so that virtue is historically intertwined with the notion of maleness in the history of the West — a theme Obscura explores from time to time in her discussions of Richard Armitage and the Roman virtues.) I’m using the term here explicitly to reflect its connotations (described in the OED) in order to differentiate it from a more general notion of masculinity. Virility involves power, solidity, health or vigor, productivity, and particularly, the capacity and desire to reproduce. A key element for me in that distinction lies in the way that modern masculinity separates desire from reproductivity (in the general sense not just of having babies, but of building and perpetuating things), even though both modern and premodern men display the characteristic desires of men that signal and thus perform their masculinity to onlookers. To make a much-too-bald distinction, the male gaze exists in both cases, but the pre-modern male gaze desires among other things for the purposes of production and reproduction, performing its desire in forms that facilitate these ends, while the modern male gaze is more narrowly focused on desire and pleasure as ends in themselves. If you’d like a too-rough sample distinction: for Guy of Gisborne and Mr. Thornton, Marian’s and Margaret’s attractions lie also and decisively (if not exclusively) in their capacity to provide children, family, position, and posterity — things that involve a figurative multiplier effect. Lucas North and John Porter, in contrast, look chiefly (if not exclusively) for pleasure, satisfaction, and (possibly) emotional comfort or companionship.

I’ll offer an example of how the differences in that gaze work in a moment, but first I want to talk about how Armitage uses the requisite symbols to perform virility and (re)productivity in Proctor’s case. The boots, for instance, which signal power and control when he wears them. (Someone who met Armitage at the stage door in June asked why he was wearing Proctor’s boots and he mentioned that he had bought his own pair. I suppose a part of living his way into the character? In any case, a third of the way through the run they seem to have disappeared from the stage door.) When Proctor wears the boots, as he does in Acts One and Three, they affect his entire stance, making him more authoritative, particularly in the way that he can use them as the axis for leaning back in suspicion, anger, and detachment when interacting with other men (as in the exchanges over Parris’ salary in Act One) or venturing forward in menace (as with his exchange with Putnam over the ownership of the forest and wood he’s about to drag out). Men perform their virility not only to women, of course, but also a means of establishing status amongst each other, and Proctor’s use of his stance and the way he moves his boots offer a powerful counterbalance to the “weighted” books of the scholars Parris (Michael Thomas) and Hale (Adrian Schiller). Part of establishing status as it affects chemistry comes when women observe men. When Proctor wears the boots, he walks with weight — even if he is running around, or shaking Abigail off. It’s also key to the way he plays these scenes that the encounters with Abigail occur in settings where he’s wearing the boots, while most of his exchanges with his wife occur when he’s barefoot. Taking off the boots reduces his status and thus the sense of his own power and self-awareness both as a member of the Salem community and in relationship to his wife.

I’ll offer an example of how the differences in that gaze work in a moment, but first I want to talk about how Armitage uses the requisite symbols to perform virility and (re)productivity in Proctor’s case. The boots, for instance, which signal power and control when he wears them. (Someone who met Armitage at the stage door in June asked why he was wearing Proctor’s boots and he mentioned that he had bought his own pair. I suppose a part of living his way into the character? In any case, a third of the way through the run they seem to have disappeared from the stage door.) When Proctor wears the boots, as he does in Acts One and Three, they affect his entire stance, making him more authoritative, particularly in the way that he can use them as the axis for leaning back in suspicion, anger, and detachment when interacting with other men (as in the exchanges over Parris’ salary in Act One) or venturing forward in menace (as with his exchange with Putnam over the ownership of the forest and wood he’s about to drag out). Men perform their virility not only to women, of course, but also a means of establishing status amongst each other, and Proctor’s use of his stance and the way he moves his boots offer a powerful counterbalance to the “weighted” books of the scholars Parris (Michael Thomas) and Hale (Adrian Schiller). Part of establishing status as it affects chemistry comes when women observe men. When Proctor wears the boots, he walks with weight — even if he is running around, or shaking Abigail off. It’s also key to the way he plays these scenes that the encounters with Abigail occur in settings where he’s wearing the boots, while most of his exchanges with his wife occur when he’s barefoot. Taking off the boots reduces his status and thus the sense of his own power and self-awareness both as a member of the Salem community and in relationship to his wife.

Then, there’s the coat (left). It’s a piece of clothing well-suited to Armitage’s physique, it’s true — for reasons similar to those that made the Mr. Thornton costume so successful; that is, it not only adds substance to his general shape, but it makes his shoulders and trapezius, already marked parts of his body, seem even more prominent — here, set in sleeves that don’t cut all too close to the actual shoulder construction of Armitage’s body adds the appearance of muscularity. (In the screen shot from the curtain call on the night they were taping you can see the actual architecture of Armitage’s shoulders during the run of the play without much covering.) Look, at left, how powerful his upper body appears; consider the ways in which the prominent elevated collar adds lines and an arrogant, lordly energy to his neck and head area; look how the patches in the coat suggest a carelessness driven by hard, muscular physical labor.

Then, there’s the coat (left). It’s a piece of clothing well-suited to Armitage’s physique, it’s true — for reasons similar to those that made the Mr. Thornton costume so successful; that is, it not only adds substance to his general shape, but it makes his shoulders and trapezius, already marked parts of his body, seem even more prominent — here, set in sleeves that don’t cut all too close to the actual shoulder construction of Armitage’s body adds the appearance of muscularity. (In the screen shot from the curtain call on the night they were taping you can see the actual architecture of Armitage’s shoulders during the run of the play without much covering.) Look, at left, how powerful his upper body appears; consider the ways in which the prominent elevated collar adds lines and an arrogant, lordly energy to his neck and head area; look how the patches in the coat suggest a carelessness driven by hard, muscular physical labor.

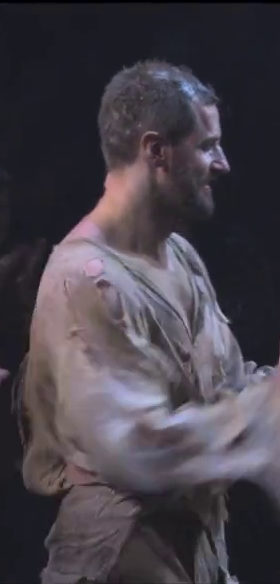

Even when Armitage takes off the coat, he seems hugely masculine (right, in the costume he wears for Act Four — try to imagine him not smiling, as he never does in the play). Of course, the torn fabric of the clothes he wears in jail emphasizes his build rather than hiding it — something that Armitage worked against during performances by strongly modifying his posture and to some extent with his makeup, so that his chest and pectoral muscles, for example, almost looked sunken under that tunic. But the beard — that quintessential classical symbol of virility — even dusted to greyish dullness, continues to broadcast the message of his virility. Note that in Act Four, he’s not supposed to be strong but weakened, and yet his capacity to build and reproduce remain represented by the beard. Establishing this status is important for two reasons — first, despite his broken words, the capacity for a productive life “after” his confession (note how often he mentions his legacy to his children in this scene) has to seem a real one to both the character and the audience. Secondly, Proctor has to have some mechanism by means of which to exercise his own power over against Danforth when the judge questions the veracity of his confession and Proctor must repudiate it. The script requires a powerful Proctor at the end — and here the connection referred to above between masculinity and virtue becomes important, for in order for the rhetoric of the play to work, we must see Proctor as fully virile (capable of exercising manly power) and also fully virtuous (and particularly, more virtuous than the other men around him, who speak in the name of the lawful state [Danforth] and the ultimate moral authority [Hale]). The beard — and the way that Armitage projects its presence by pushing his chin out, as he has done all the way through the play in moments of threat — connect this imprisoned, initially apparently broken Proctor with the powerful man of Act One.

Even when Armitage takes off the coat, he seems hugely masculine (right, in the costume he wears for Act Four — try to imagine him not smiling, as he never does in the play). Of course, the torn fabric of the clothes he wears in jail emphasizes his build rather than hiding it — something that Armitage worked against during performances by strongly modifying his posture and to some extent with his makeup, so that his chest and pectoral muscles, for example, almost looked sunken under that tunic. But the beard — that quintessential classical symbol of virility — even dusted to greyish dullness, continues to broadcast the message of his virility. Note that in Act Four, he’s not supposed to be strong but weakened, and yet his capacity to build and reproduce remain represented by the beard. Establishing this status is important for two reasons — first, despite his broken words, the capacity for a productive life “after” his confession (note how often he mentions his legacy to his children in this scene) has to seem a real one to both the character and the audience. Secondly, Proctor has to have some mechanism by means of which to exercise his own power over against Danforth when the judge questions the veracity of his confession and Proctor must repudiate it. The script requires a powerful Proctor at the end — and here the connection referred to above between masculinity and virtue becomes important, for in order for the rhetoric of the play to work, we must see Proctor as fully virile (capable of exercising manly power) and also fully virtuous (and particularly, more virtuous than the other men around him, who speak in the name of the lawful state [Danforth] and the ultimate moral authority [Hale]). The beard — and the way that Armitage projects its presence by pushing his chin out, as he has done all the way through the play in moments of threat — connect this imprisoned, initially apparently broken Proctor with the powerful man of Act One.

So the beard, coat and boots function as symbols of virility — as does Proctor’s rather direct glance (the modifications of which in each case I’ll explore more fully below. Proctor looks directly, and looks burningly, whether up from under his eyebrows in Act Three or down upon his challenges as in Act One. Importantly, however, his glance doesn’t signal desire in the same way as his modern characters do.

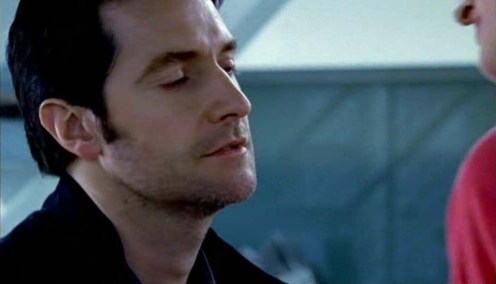

Look, for the purpose of contrast, at Lucas North, whose glance follows Sarah Caulfield out of the morgue room in the first episode of Spooks 8. Lucas has the signals of modern desire down to a tee — pumping up the lascivious glances both secret and ostentatious that adults take at each other nowadays to just the point at which we as audience members can no longer ignore them.

***

As Lucas (Richard Armitage) watches Sarah leave, he takes a very unsubtle look at her rear, in Spooks 8.1. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com

As Lucas (Richard Armitage) watches Sarah leave, he takes a very unsubtle look at her rear, in Spooks 8.1. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com

This mode of interaction becomes incredibly noticeable at the point in Spooks 8 where Lucas has clearly realized that Sarah is deceiving him (the closing scene of episode 8.5), and she becomes primarily a tool for gaining more information about “Nightingale” and an attractive sexual partner

***

Lucas North (Richard Armitage) takes a subtle glance at Sarah Caulfield’s (Genevieve O’Reilly) chest in Spooks 8.6. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com

Lucas North (Richard Armitage) takes a subtle glance at Sarah Caulfield’s (Genevieve O’Reilly) chest in Spooks 8.6. Source: RichardArmitageNet.com

***

This is the look of desire — not of generativity.

OK, this is 2,000 words, so I think I’ll stop here for now and break the piece about chemistry with female castmates into a separate post.

***

to part 2

Yikes, I always look forward to your analysis with some trepidation (if that is the correct word) because I know I am going to be reading and absorbing for like two hours! First is the yeah, a new post. Then the quick read through (where much goes over my head I confess). And then the slower read through trying to make all the connections and pondering everything. And then the read through with all the shooting off to the links and what not. And then another hour spent cause, damn, some of the ideas and pics brings to mind some stuff I want to go have a look see at again.

I am enjoying your constrasts of John Proctor with modern Lucas and Porter as it helps make things clear for me. The meaning of virility was interesting to me . Looking forward to Part 2, but still am digesting Part 1. I look forward to re-reading everything again that you have written about The Crucible once I have had the opportunity to see the filming of what must be an incredible performance of this play.

LikeLike

Thanks Heather ! 🙂

LikeLike

How happy I am that you went to see “The Crucible” so many times! Now I can re-live the play even weeks after my own experience when I read your analysis!

And I guess you kind of answered my question in my own first blog post about whether there was a deeper meaning to the characters being barefoot and wearing shoes. Thank you!

Looking forward to the next piece!

LikeLike

Having absorbed every word of Part 1, I’m holding my breath while waiting impatiently for Part 2….

LikeLike

Can we please get part 2 soon? Please?

LikeLike

Yes — I will shoot for tonight. I have to teach dad how to use his computer, today.

LikeLike

Looking forward to it. As you can tell, a few of us are anticipating your take on the chemistry of RA and his leading ladies.

I hope your dad is an adept student 🙂

LikeLike

Really enjoyed reading this and am looking forward to part 2. Also, had to click on the link of related items (the “Raw Material” one) — are ya’ll sure we don’t want/need an 18+ page for him? ’cause….dayum!!!

LikeLike

Gosh, I love this……..

(I always had the impression when I saw early pics of RA with his boots at the stagedoor in June that he needed them as some kind of protection. (Being especially vulnerable in the course of the rehearsals and the previews))

LikeLike

Saved this for my bedtime reading last night, but i’ll have another read of it today as thoroughly enjoyed it! So well written. I felt you got it spot on in terms of how he makes Proctor into a desirable man of those times, when a lot of life was about survival and virility mean such different things. ( reminded me also how procreating was about survival and how Putnam talks about how the Putnam, seed is all over 😉 so how come his children have all died). I always wondered if Elizabeth chose Proctor as a husband because he was a viable partner, strong, capable of work and willing to do a lot of it and how much of it was attraction? (his more poetic qualities, passion??) Fascinated to read your take on it in part 2.

PS the boots… ahh, didn’t realise they were his but i did notice same in photos, wondered why he had chosen them. Probably being both more attuned to Proctor but also breaking them in as he was having to wear them barefoot and that can’t be comfortable.

LikeLike

Thanks. Hopefully today will be a calmer day! I think he had two pair, based on what what he told the fans; a pair he wore for the costume and a pair he purchased himself.

LikeLike

[…] that this took so long. Continued from here. It occurred to me after publishing that, that four years ago I wrote a longer analysis of Richard […]

LikeLike

Virile Armitage, or: richard armitage + samantha colley + anna madeley in The Crucible, part 2 | Me + Richard Armitage said this on November 3, 2014 at 5:47 am |

What a thorough and thoughtful analysis, from Proctor’s head to his toes. And we are only halfway. I am jealous you saw the play so many times (only once, for me) and grateful at the same time, because your observations and subsequent posts are so informative. When he talked about his Proctor boots, I was reminded that he “needed” to wear his Thorin boots to get into character. Do you think it was particularly difficult for him to project Proctor’s virility when he had to be barefoot and beaten? He did a masterful job of doing that without the coat or boots. So at the end of the play, all he had as tools to create Proctor’s power was his voice and body. I am sure you will be getting to this, but I just had to note that while his acting was wonderful to watch in the play, your insight makes his performance even more impressive in hindsight. Thank you for highlighting his talent so well. When we watch the download, I think we will be able to enjoy the play even more, with the knowledge you have shared with us.

LikeLike

I think he’s equally virile in Act Two — so the boots don’t affect that virility, although the bare feet reduce his status.

Thanks for the kind words. This was a really great performance — I remember thinking while watching him that if we’d been able to see this years ago we’d have scoffed at the idea that he was only gaining roles because women loved him. Because I saw more of what he can do in this performance than I ever have …

LikeLike

[…] I’ve tried to suggest in my posts so far about Richard Armitage’s performance of John Proctor’s masculinity, a…, lines drawn around sexuality were different in the past than they are today. I want to continue […]

LikeLike

Richard Armitage characterizations: me + John Proctor as lover | Me + Richard Armitage said this on February 2, 2015 at 4:01 am |

[…] general review of Adrian Schiller’s performance in the play. Here are posts where I discussed Armitage’s performance of virility as John Proctor, and his chemistry with Samantha Colley. Oh, yeah, and I discussed his use of microexpressions in […]

LikeLike

Nipple, nipple, nipple! I’ve been informed that I’m not taking The Crucible on screen seriously enough | Me + Richard Armitage said this on March 21, 2015 at 7:13 pm |