richard armitage + dance + “the circus”: a thought exercise on the self and biography

[This post is a result of a number of conversations I’ve been having lately and finally got catalyzed by this, so thanks!]

This morning I saw a headline in my email about new information about Richard Armitage’s early career. This topic always intrigues me. (If you’re interested in what I made of it four years ago, click here; I’d revise some of that now in light of information that has emerged since then, and I’ve made notes on the files, I just need to sit down and do it.) So I clicked on it immediately. It turned out that it was a source that Annette, the builder of Richard Armitage Online, must have had access to, as appears in her biography page (the site was developed through the collecting efforts of a number of early fans, not just Annette). I suspect that it’s a cast page from the program for 42nd Street from 1990.

This morning I saw a headline in my email about new information about Richard Armitage’s early career. This topic always intrigues me. (If you’re interested in what I made of it four years ago, click here; I’d revise some of that now in light of information that has emerged since then, and I’ve made notes on the files, I just need to sit down and do it.) So I clicked on it immediately. It turned out that it was a source that Annette, the builder of Richard Armitage Online, must have had access to, as appears in her biography page (the site was developed through the collecting efforts of a number of early fans, not just Annette). I suspect that it’s a cast page from the program for 42nd Street from 1990.

But. Something stuck in the back of my mind. After a while, I realized there was a piece of information there that I hadn’t seen. “Allow London,” the name of Armitage’s “circus” production in Hungary, had been known, and I’d googled it a long time ago and not found any additional information. But the name of the director was something new: Dougie Squires. Huh. So, I googled that this morning and learned that Squires was one of the more important choreographers in popular dance on English television in the twentieth century. He was awarded an OBE in 2014, and here’s his own description of his achievements. Multiple sources (here’s one) mention his importance in four respects: integrating elements of street dance and popular dance from the 1960s in his compositions for the BBC, which moved dancers from the background to the foreground; ending the practice of dance companies arranged by uniform height and weight; mixing up the genders in television dance, and finally, pushing for the ethnic / racial integration of television dance in the UK. He has had a stellar career as a choreographer, including working several times for the Queen.

OK. So. So what?

To understand my line of argument in this post, it might make sense for you, the reader, to think about an important turning point in your life, if possible, a decision you made. When did it occur? Why did you make it? How long ago was it? How did you describe it at the time? Five years later? Ten years later? Twenty years later? I have one in mind for myself, the most decisively conscious move of my life: my decision to convert to Judaism.

Richard Armitage at a dance competition while at Pattison College, with Miss Pat (at right). Date unknown, but 1985 or after to fall 1988. Source: Pattison College

In the sources we have available, although Armitage has been uniformly positive about his time at Pattison College, the role of the circus and dance have played in his relaying of his own biography has largely been ambivalent. Early press after North & South used his past in dance as a way to illustrate his persistence and industry although he was unsuited. In 2004, he described some of the things he did in Budapest and they don’t really sound like dance. This is the point at which he introduced the information that he did his stint in Budapest in order to get his Equity card, a point in his self-narration that has remained constant ever since. It’s a sort of key moment of the Armitage legend that dancing in a Sarah Brightman video convinced him he was on the wrong track and motivated him to change the sort of projects he worked on and ultimately, apply to LAMDA. What I know about the seaweed incident is documented here. In 2005, he described the circus as a “movement theatre type mime group” and describes himself (following the initiative of the interviewer) as feeling “ridiculously silly.” In 2006, he also discussed lessons he learned in musical theater as an example of how he learned that show business is unfair and that he needed to discipline himself more and not let himself rest on his achievements. In a radio interview in 2008, he spoke with a certain amount of amusement in his voice about his youthful desire to copy Michael Jackson. Although some fans might have wished to see him back in musical theater, his statements about it became increasingly negative; for instance, in 2013 he referred to his early theater experiences as “tits and teeth” and said they weren’t stimulating him enough. And although I don’t have links for these assertions (will come back to fish through my notes when I am in the room with my notebook and have a little more time), in 2014 he talked about Gillian Lynne encouraging him by telling him that “he didn’t belong here [in musicals]” and encouraged him to move on, and also stated that “other people were better at it” and (paraphrasing) that the fact that he always had to be told to smile meant that he really wasn’t enjoying it.

But the Dougie Squires data point fleshes this picture out a bit and raises questions about the story as Armitage has told it over the years. We already knew that Armitage had worked with both Lynne, now Dame Gillian, who did the original choreography for Cats and The Phantom of the Opera, and with Kenn Oldfield on some of his West End shows. If we add Squires to this picture, we can see that Armitage worked as a youth with two of the more illustrious choreographers on the London popular scene (Squires and Lynne) and one (Oldfield) who, if not quite at the same level, was still extremely respected. In other words — yes, Armitage was probably persistent and yes, he had to have a short hat for 42nd Street because he was taller than the average dancer, but there’s no way he’d have made it into any of those ensembles without quite a bit of skill. And listing the Squires connection in the 42nd Street program suggests that “Allow London” was a bit more than simply the path to an Equity card, although it must have been that as well. It would have been a chance to work with a renowned choreographer whose glory days in the 1970s and 80s were over but whose name still meant something in the dance world, who would go on to do a great deal of well-regarded and widely seen work, and perhaps a path toward more work in the area of dance. Squires “wrote over 30 pantomimes to develop young talent” and it’s reasonable to conjecture that “Allow London” might have been a show like this. Budapest and the circus and elephants and black tights, yes; but in a production intended to be artistic and which Armitage may, at one time, have seen as a stepping stone to more work in a larger artistic context than simply that of paperwork and a union card.

Richard Armitage as Felix in The Normal Heart while at LAMDA. Date unknown but after 1995 and before the end of 1998. Multiple sources, including tweet by LAMDA.

There’s a tendency for many fans to play this down, simply because Armitage always does, as we’ve seen above. His current narrative is one in which musical theater was a source of frustration that he was happy to abandon, and in which he always wanted to be an actor working on texts. But the Squires data point (before I argue for something strongly, I always try to have a minimum of three solid data points) suggests a different story, one in which the desire to leave the musical theater and attempt other roles on the stage was not set from the beginning but developed over time. I think we can point to a crystallization of this desire into action around 1995 — we are aware of no more musical roles he took after that — and in either 1995 or 1996 he entered LAMDA (he gives 1996 as the date but as we know, his command of detail like this is not always precise; Richard Armitage Online gives 1995 as the date, which would make sense if he did indeed do a three-year course, as is usually reported, although at least now LAMDA will shorten its three-year course to two for people who have worked extensively in theater before and Armitage would certainly have qualified). But he was by no means an “also ran” in musical theater and given what we know, if not for his own distaste for the medium, there’s no reason to think that, had he remained injury free and continued to seek such roles, he might not have gone on to even more roles in that medium. (I saw reported on a notorious gossip site two years ago that he’d been offered the lead in Hair in 1996, but given the site, its anonymous quality, and my inability to make this data point solid, we need to consider this information apocryphal).

So why talk about “Allow London” as a “circus” and his other musical theater experience as unpleasant, frustrating, and something he always wanted to leave? I think it’s crucial to consider when he’s saying what. Armitage’s first surviving interview (that I am aware of) dates from 2003. It’s a common tendency in self-narrations for humans to justify our past decisions as inevitable or correct. Now is the time to think about your turning point, how you saw it at the time, and how you have seen it since, and most importantly, how you would talk about it if someone asked you about it today.

At this point only Richard Armitage knows what actually happened in his mind and heart in Budapest in (we think) 1990 (there has been some discussion about this, because his remarks about it have been so inconsistent — see comments here). But what Armitage’s remarks on all of this say to me is that there are clear signs that he was assiduously and enthusiastically pursuing the professional connections he needed in musical theater and thus cultivating his dance career after leaving Pattison College and for several years afterward. However, by the time he was in a position to be interviewed about his professional path in 2004, when he initiated the “circus” account of “Allow London” — fifteen years after leaving Pattison College, eleven years after the Brightman video, nine years after leaving musical theater, and five years after finishing at LAMDA — he not only saw those years differently, but also wanted to present himself to readers and possibly employers differently, as someone on quite a different trajectory than those experiences had suggested.

“Running off to the circus” is such a classic, albeit trite, trope that almost no interviewer has been able to resist it, of course, and Armitage couldn’t pretend that he had never been a dancer or worked in musical theater. So Armitage’s self-narration — which has consistently been one of industry, hard work, and the success of the underdog — reframed the Budapest episode and his dancing afterward as something he needed to do to get something else he wanted more, and an example of his willingness to do anything to succeed at his aspirations rather than a demonstration of the skill that it surely provided as well. Perhaps there was something there of the difficulty of getting spoken stage roles without the professional theater training he found for himself after 1995; or I could imagine that there is some sort of looking down by dramatic actors toward their compatriots in musical theater as less serious; and if I can imagine that, I might postulate that a dancing past might not be the best credential with which to compete with one’s fellows at the RSC. It wasn’t exactly an embarrassing episode in 2004, but it could be seen as reflective of a sort of lack of taste, unless Armitage had only worked in out of necessity until he’d been able to pull himself up into work of higher regard. It’s interesting, the tact with which he refer to Cats in the Anglophile Channel interview as “of the 80s.” He was in it, but it’s over, is the general tone.

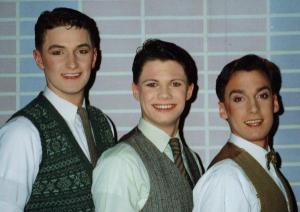

Richard Armitage, David Massey, and Timmy Ward in costume for 42nd Street. Source: Timmy Ward Twitter

I honestly don’t think that after LAMDA, Richard Armitage ever spent a second seriously contemplating a return to musical theater (the hopes of some fans notwithstanding), because what the data about Squires added to my picture today confirms is that had he loved it, a career would have been there for him. Checking up on the people he was in Cats with suggests that most of them went on to successful, if not superstar, arts careers. However, it’s interesting that his statements about it became more forceful in the years after The Hobbit and in the context of The Crucible.

I hypothesize that this might be due to two factors: first, by the time the first Hobbit film came out (2012), the decision to switch out of musical theater (if we place it in 1994) was eighteen years in the past. Connections and friendships from that period would have persisted only if they had a stronger basis than simply shared memories or ongoing collective work experiences. One of his friends from the dance era had posted a dance video from 1991 in 2010 and then made it private until 2014; and it was interesting that the fall that Armitage joined Twitter, that person tweeted Armitage with pictures of him in boxer shorts and in costume from the 42nd Street days. It felt like an “I knew you when” moment rather than a current friendship, and if it was publicly acknowledged, I didn’t see it. Second, on some level, appearing in a lead role on an important London stage might have served as some kind of liberating vindication that made it easier to speak more openly about his current feelings about the past. In his birthday tweet, Armitage recently termed working in the New York theater district a coming “full circle” from his days in 42nd Street. I wonder if his success as a dramatic actor at the Old Vic was a similar moment — a final sign that his decision all those years ago had definitely been the correct one, and that he felt freed from what had earlier felt like a need not to speak too unguardedly about his current feelings about his musical theater days.

Even if we can say nothing definitely, it’s an interesting question to contemplate simply because our own stories about ourselves (did you think about your own turning point?) tend to change over time. If you asked me why I converted to Judaism I would tell you a different story now than I would have in 1988 — or 2008. At some point, I was a Jew longer than I’d been a Christian, and as Armitage moves further and further from his days in musical theater, those six years — even if I think they influenced him very decisively, not least in his constant statements about the significance of how a character moves — take on more and more the role of an episode as opposed to an ongoing presence. It’s not entirely clear which story is most accurate, simply because what these decisions mean changes in the context of an ever developing life. And this — and the fact that our subject positions change as each day passes — explains why biographies and autobiographies get not only written, but also rewritten.

Really interesting, and way to go putting it all together in one way that makes a good bit of sense….

LikeLike

Thanks. I was just flipping through my notebooks from 2012 and 2013 — I need to get back to this. Good stuff to discuss.

LikeLike

What you describe is pretty common when a performer’s development changes from one style or medium to another. It tends to evolve gradually and the change only comes when they’ve woken up to a little more self-knowledge. And it is a very typical experience for a performer who is trained from a young age in musical theater, dance and song, or music (as most performers are) to stick with musicals for a long while unless some formal education interrupts it. Having the insight and self-knowledge to make that shift in mid-20s before his formal education took over is what I find remarkable in Armitage.

LikeLike

Thanks for the additional info. My impression is that this general process also applies to a lot of the academics I know (and, for that matter, to a few of the writers). I don’t know many scientists, though. I should ask some of them about it.

re: Armitage, one thing that really complicates explaining what happened from the outside is his sloppiness with dates (this is something historians are always frustrated by when examining sources: we’re observing the timing, why aren’t YOU??? — this is because our training teaches us to be super-preoccupied with causality) combined with things that haven’t always been transmitted correctly and the thing that I noted above — that Armitage and humans in general adduce different explanatory factors at different times. For instance, one of the key steps in the process according to him was seeing productions at Stratford while doing his A-levels, which suggests there was a very early seed for this process (pre-1988). Other sources name Adrian Noble’s Midsummer Night’s Dream at Stratford as decisive, which would mean it was 1995 or so (coinciding with the general turn at the end of Cats toward drama). So there could have been a relatively early self-awareness, for instance, that what he was training to do was not much like this thing he was seeing at Stratford and being fascinated by. I also haven’t talked here about his reading. There’s a single hard to put one’s fingers on reference that he might have taken some university classes that involved literature, esp Victorian novels. If that happened, it would most likely have had to have happened relatively well before 1995, and it would suggest an early date for the turn. Then you look at the other sorts of things that he likes to read (he’s cited Bulgakov, J.G. Ballard, John Fowles) — these are not the kinds of things typically sought out by the auto-didact. His teen interest in fantasy could have brought him to Ballard, but one kind of thinks you need a bit of a push to look at something like Bulgakov. Contrasting that you have him terming “Crime and Punishment” an “aspirational” read that he did while he was working on Macbeth at LAMDA.

So I guess what I’m saying is there a ton of room here for coming up with various dates for a turn and his own statements, which imply a relatively constant drive toward the path he ended up on at LAMDA, are primarily problematic in light of other things we know about him but which he doesn’t discuss (as much, or at all). Still, I really wish someone could go back and interview him in 1996 or so. Like, after one of those LAMDA shows that London theater agents were said to attend regularly. Maybe after he was in the Sam Shepard piece where his tutor was disappointed.

LikeLike

I remember him tweeting something once about all of the productions you mention that had an impact (the Adrian Noble MSND or the productions at Stratford) as well as Michael Gambon in Volpone, which was at the National in 1995/1996. I chuckled because I was doing an internship in London that year and saw everything at the National, including that Volpone and the Fiona Shaw Richard II. It was a season of plays that radically changed my conception of theater, which up until then was a lot of musicals and Broadway mainstream plays. So I understood exactly how seeing that could have an impact. (I still wound up directing “You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown” for my first time out, so. . . yeah, it can take a while. But a paid gig is a paid gig!)

LikeLike

You should blog about those productions. Would definitely add to the knowledge base!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great read! Thankyou for putting all those thoughts together. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

This was a thoroughly enjoyable read and a trip down Mr. Armitages memory lane. A very well written article. it is amazing the paths we all choose, do we go left or right? either way it is so interesting where any one of us can end up and we always hope we have chosen well and will end up happy with our choices.

LikeLike

I was pondering the counterfactual, itoo. I was thinking, well in the one case (drama didn’t work out and he left the theater permanently) we wouldn’t know who he is at all, and in another case (drama didn’t work out and he went back to musical theater), odds are that a much smaller group of people would be aware of him. In either of those cases he would be telling a very different story about the years from 1989 to 1994. But obviously personality factors also pay a role and there’s a very obdurate streak in him — I feel like we are seeing it all the time — and that tendency shapes this story as well: Richard Armitage, determined young man.

LikeLike

I think you found some puzzle pieces that slipped under the chair and went missing for a while. Although I am by no means an expert who has read every sliver of information about RA that is out there, I think you came up with some new thoughts/connections/speculations. It wasn’t clear to me what exactly he did in the circus to earn his card. He always talked about the elephants and gave me the impression he was some kind of acrobat assistant. He has been vague regarding his circus work and I don’t think he has ever said he danced there (could be wrong). We know by what he doesn’t tell us that singing and dancing probably weren’t his thing by then, because he barely talked about it. Maybe a song and dance man is a second-class citizen in the theater world. Like being a model-turned actress, and he just doesn’t want to revisit his musical past. He sounds like he was bitten by the acting bug early, maybe while playing a elf, but the singing/dancing bug just flew by with a gentle nibble. I am glad his career turned out the way it did, for him as an actor, and for us, as consumers of his work. Did anyone ask him about singing in the Hobbit? Did he enjoy singing as much as we did hearing it and going back to his show business roots? Maybe he mentioned it during the brief time he was going to be in the rock star production. Anyway, Serv, you have raised some interesting points and topics for discussion, as usual.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment —

I think one element in all this is how anyone understands his possibilities and that is heavily dependent on the horizons of his world. (I’m reminded of someone asking me around 2003 or so why I didn’t go to an Ivy League college. I’m not sure I’d have gotten in, but the fact remains that those places were not on my family’s horizon, not even aspirationally.) A kid is exposed to a certain panorama of arts experiences that include the regional youth symphony, and takes dancing lessons — lore says, because he has pigeon toes — and decides he wants to go to what is essentially a stage school (we’ve never been able to establish how Armitage even know about Pattison’s although I’ve hypothesized about it) — even though he is shy and not necessarily interested in the speech aspect, at least as a fourteen year old. If you look at his cultural world, it probably didn’t include things like visits to the RSC at least until he was already enrolled at Pattison (which at the time was called “Pattison’s Dancing Academy”).

So that raises the question: in what kind of mood did he experience his A-level years and departure from Pattison College? Was it a sort of relief that he go there and then he saw some plays and thought, I want to do that instead! but it will have to wait (if so that would be an exceptionally mature thought process for a teenager). Given what I understand about how most adolescents experience their lives, most career thinking at that age is much more hazy (“I like this, I like that”) and very few teenagers are thinking ahead more than a few months or a year at most. (This is true of a lot of college students, too.) Which isn’t to say he didn’t. But my guess is that the frustration with musical theater came more in the atmosphere of actually doing musical theater and seeing its limitations. Success is getting to repeat exactly the same thing in exactly the same way, sometimes for years, because that is what the audience is paying for, to see that same great musical and hear those same great songs that their friends heard. If you’re living in Leicester or Coventry, you see less than if you’re living in London, where you can see and experience a lot more, so your horizons may widen and so your aspirations change and grow.

re: Hobbit — he’s never said “I loved to sing” but he has said he wished there had been more songs in the films (as there are in the book). He’s also said he didn’t want it to sound like professional singers but like dwarves singing, rougher.

There’s a sort of subdued vibe (not the top note, but there) he has about boredom and not wanting to repeat himself (in types of work he does, in not casually signing an American tv contract because they are routinely for seven years, in liking stage because it’s like abseiling, etc.). It definitely came into play around 2009-10: frustrating he was feeling about the atmosphere of series tv.

LikeLike

Wow, I think I’ve been on this post for almost three hours. I’ve been reading links, and links within links. You’ve gathered so much great information here. Thank you for the ” background, childhood… ” link in particular. This has all filled in so many holes, and answered so many lingering questions. I can’t thank you enough.

LikeLike

Thanks — I’m always happy when the “back issues” are useful!

LikeLike

😊

LikeLike

[…] because there often seemed to be a need in the air to see him as an underdog. But at the same time, he has regularly told the underdog story about himself (it’s strongly present in his early press). “Insecure actor attracts insecure […]

LikeLike

Q: When will Richard Armitage’s fandom reject his victimhood narrative? A: When Richard Armitage stops feeding it to us | Me + Richard Armitage said this on December 15, 2018 at 4:32 am |