Review: “Brain on Fire” #richardarmitage (Toronto trip part 1)

[I was privileged to see the film on Saturday afternoon at 1:30, with fellow fan Babette — who I am outing in case she wants to leave her impressions in the comments as well. I will write this in in three pieces — a general review; a discussion of Richard Armitage; and other impressions. These posts are based on notes I took during the film; a half hour right after the showing taken to jot down impressions; and, of course, twelve hours on the road yesterday to think about it. I have not paused to read any review that I hadn’t seen before I left, so I may repeat some information you already know. I’m incorporating paraphrases of things that director Gerard Barrett said in the Q&A afterwards into this portion of my comments.]

[ETA: typos and syntax. Sigh.]

Partial picture of the Brain on Fire cast, tweeted by Jen McLean Angus on July 20, 2015. Richard Armitage, Thomas Mann, Charlize Theron, Angus, Rob Moloney.

It’s hard to know how to review a film like this. I have my own allegiance(s) — to frankness and also to Richard Armitage, so I’m hardly non-partisan. It’s also unpleasant to criticize a film that adapts a book written by a survivor of a frightening illness — anything I say that’s not unreservedly positive makes it sound like I’m denigrating Susannah Cahalan’s experiences and struggle or the way her family fought for her. (As you know I didn’t care for the book, and as many of the book’s problems carry over into the film, let me preface this piece by nothing that I have nothing but respect for the victims of this disease and their families.) Summing up: this post reviews the film solely as a work of art.

Standing ovation for BRAIN ON FIRE last night at the TIFF World Premiere. 2,000 people. @ChloeGMoretz @scahalan pic.twitter.com/mCe2P1jvaY

— Gerard Barrett (@gerardbarrett) September 17, 2016

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

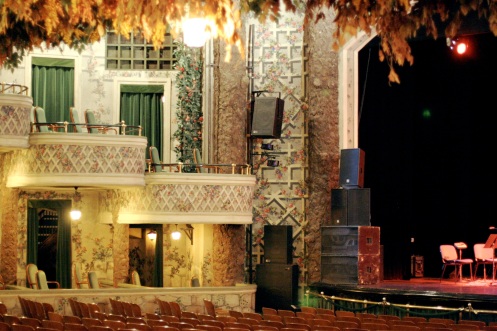

Babette and I saw the film in a large theater (ca. 1,500 seats) — I didn’t look into the mezzanine, but I would say that the floor was about 90 percent full. Babette was a great guide and got us into line about forty-five minutes before the showing, and were in the first 150 or so people to enter, but the line was long behind us despite the constant rain the whole time we were in line. So there was a lot of interest. Judging from the questions after the showing, the vast majority of the audience had either read the book or had some kind of interest (personal, professional) in the disease. Some people seemed to be interested in Gerard Barrett (the director) more specifically. I didn’t overhear anyone who sounded specifically like an Armitage fan, nor did I see large groups of people who were like to have been fans of Moretz (although the ticket price and the setting may have meant some of her target audience was excluded by circumstance). The later audience segment is important, and it is a bit concerning that they were not present.

The Winter Garden Theatre in Toronto, where we saw the film. Dried beech leaves hang from the ceiling. Really. It’s an amazingly retro space.

My impression was that the audience enjoyed the film and the camaraderie of the festival, despite the damp wait. I meant what I said when I remarked earlier that it wasn’t anywhere near as bad as I’d read. And yet the film is problematic. I think the standing ovation Barrett describes was given for Cahalan, her story, and the way she overcame her troubles, not the film itself. I’ll skip the recap that customarily goes in a review like this because the story is not complex; most of us are familiar with it; and the film is strikingly faithful to the first two-thirds of the book. It drastically truncates Cahalan’s recovery, but Barrett implied that one possibility is the audience will turn to the book to “find out what happened.”

First, however, to its strengths. I think it does extremely effectively what it intends to do (I’ll say more about this below). The intent of the film is clear and all of the scenes contribute to that end. It’s short, tight, taut, without detour. It follows a compact, comprehensible story arc. It has a striking first scene that draws the viewer in. While the first half of the film has its problems, the second half, when Cahalan’s family is drawn into her treatment and the search for her cure, is compelling. Unlike most “disease” stories, it’s not full of disgusting moments (I really appreciated this). It succeeds in creating sympathy for the protagonist; what is happening to Moretz comes across as genuinely worrisome and then disturbing (even if I knew how it ended, so it was not remotely suspenseful for me). Despite a lack of intrusive or even apparent cinematography — I am also bookmarking this question for more discussion — there are some subtle elements of cinematic or artistic interest: for instance, the way that the camera recurs without lingering over particular symbols such as Cahalan’s “flight risk” bracelet in the hospital, or Tom Cahalan’s moleskine notebook. Admittedly it would be helpful if the film indicated more obviously why these elements recur. It has an excellent supporting cast. Apart from Armitage, who has the biggest role of the secondary characters, and about whom I will write more, we could single out the work by Carrie-Ann Moss as Cahalan’s mother, Rhona, who does a great job despite not getting very many lines, and Tyler Perry as Richard, Cahalan’s remarkably understanding boss (who has the name Paul in the book). On the whole, it does quite a bit with its reputedly small budget.

And now the problems, and the reasons why, although the film apparently already has a distributor, I think it will not find its way onto many theater screens. One is that it wasn’t clear to me who should want to see this film, besides the people who came to the film because they were already interested in the disease, because the style of the film excludes some of the typical people one would assume might want to see it.

Brain on Fire occupies an unusual space between the quality of the usual “problem” film made for TV and the greater aspirations of motion pictures intended for the screen. The remarks of the reviews that I have read not withstanding, the film is not really a “weepie” — the film’s performances and cinematography are too sober for that, and while they seek to evoke sympathy for Cahalan, they do not ever seek to evoke tears. Although there are some obvious tropes of the disease film here, they are not penetrating in the way that the are expected to be for the made-for-tv piece, in which a largely female audience is watching for these and enjoying their pathetic execution. The decision not to explore Cahalan’s rehabilitation means that the whole stereotypical “comeback against all odds” theme is eliminated from the film. One exception is the appearance of Souhel Najjar in the role of “intrepid, kind physician as savior,” but given the fact that the real Souhel Najjar is a Syrian-American, played here by a highly-respected Iranian-American actor, Navid Negahban, I can overlook it out of happiness to see such a positive portrayal of and by immigrants. Nor is the film — despite its female lead, and the fact that anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis occurs most frequently in women and people under twenty-one — all that clearly directed at the Moretz’s audience demographic, so it doesn’t fit at all into the genre of “trials and tribulations of a character played by a beloved actress” that teenage girls often enjoy.

The most obvious problem — to put it point blank — is that Chloë Grace Moretz is badly miscast. She has, as Roger Ebert famously wrote of her under other circumstances, “presence and appeal,” but what she has to give is insufficient to fulfill the demands of this role.

First, she is too immature to play Cahalan both physically and in terms of her manner. Moretz was eighteen when she made the film and, apart from her upper lip, looks about sixteen here; she’s playing Cahalan, who was twenty-four when the disease struck. It’s not just that she looks young; it’s that she doesn’t carry herself like a mid-twen, and definitely not one with the requisite poise obtained at an upper-tier, privileged U.S. university (Washington / St. Louis), eager to succeed in her first professional role at her dream job. This insufficiency is particularly obvious in the office scenes, which are in themselves problematic for other reasons. But her colleague and close friend, Margot (named Angela in the book), is played by Jenny Slate, who is fifteen years older than Moretz and looks twice Moretz’s age. On the fundamental level, Moretz does not plausibly appear twenty-four.

The other problem is that Moretz apparently lacks the artistic preparation to portray the active mental illness that the first half or so of the film demands. Much of this is her certainly not her own fault; she was directed by Barrett who, when asked afterwards how he coaxed out Moretz’s “fearless” performance, said, “we trusted each other.” My problem with her portrayal of the altered states of Cahalan’s illness is not so much that it is shrill and monotonous, although it is, and given the film’s goals (more below), this is the only real problem of its first half, which is abated once Cahalan lands in the hospital and her character becomes more dependent on other characters. It’s more that Moretz seems to be aware neither of the inner state of an adult who’s experienced altered consciousness or perceptual difficulties, nor that she seems to have considered how people suffering from mental illness or brain disease or injury look to others from the outside.

Through the scenes that precede Cahalan’s hospitalization, Moretz has one look — a sort of adolescent astonishment — and one style of acting that swings between the poles of wide-eyed “I can’t believe this” grimacing, and shouting, over the top posturing. It makes her look like she has not thought about the inner state of someone in this position nor has she reflected on how it looks from outside (apart, potentially, from the tapes of Cahalan in the hospital). I’m no expert on mental or brain illnesses; however, I do know that people who are experiencing hallucinations or other perceptual problems do not usually escalate to manic states, because they fear that other people will think they are crazy; they are careful to hide their reactions to what they experiencing for that reason. Equally, I’m no expert on manic states, but I know that they are characterized by much more than rapid mood swings, shouting, jumping on furniture and feigned sobbing. Barrett and his cinematographer (Yaron Orbach, who did a season of Orange is the New Black) do have the wisdom not to overwhelm the audience with the stereotypical camera effects that typically characterize tropes of perceptive or cognitive challenges in film. There’s some blurring or rotation to indicate dizziness, but it ends at that, even though the book itself offers multiple descriptions of how Cahalan saw her world as the disease advanced that would have given them chances to experiment. This restraint means the film reads very naturalistically, and (see below) that is a big piece of the intent of its makers, but in order for that narrative strategy to work in a fully convincing way, the object we are observing (Moretz as Cahalan) must itself look believable and present some sort of point of curiosity. Nothing about how Moretz acts as the ill Cahalan leaves anything for the viewer to wonder about.

An image of the real Susannah Cahalan experiencing a hallucination in the hospital, from closed circuit video of her hospital room. This image was distributed in combination with publicity for Cahalan’s book.

Moretz’s failure ever to leave us as viewers on the fence about whether Cahalan is ill in turn creates larger problems for the verisimilitude of the film’s basic premises. As a start, neither Babette nor I found it credible that a coworker could behave the way Moretz’s character does in a crowded workplace for several weeks without generating a more negative response. The film’s one notable narrative addition — in a nod to current events, the interview that Cahalan does in the book with John Walsh is changed to one with a character who resembles Anthony Weiner — does not help in this regard; it feels more like a cheap joke than a demonstration of Cahalan’s problems. I think that even at the Post, a paper known for tolerating quite a bit, a reporter would be fired for what Cahalan does in this scene. I am certain that if I decided to sit cross-legged in the middle of a New York subway platform for a long period of time, a few people would at least ask me if I needed help; if I tottered on the edge of one looking disoriented, certainly at least one fellow passenger would alert the MTA. While I am certainly willing to attribute a certain big city callousness to New Yorkers, surely average New Yorkers aren’t quite this cold to odd things that people around them are doing. Yet in contrast to the movie character, the real-life Cahalan persisted in her delusions, paranoia and hallucinations for several weeks without interference, which suggests that her self-presentation was credible enough that people, including those who knew her well, didn’t initially think about it. Indeed, this state of affairs is an integral element of the narrative, in which professional after professional writes off Cahalan’s symptoms as either not significant, not symptomatic of illness, or else a typical emotional or medical problem rather than a rare auto-immune disease.

I could say more about Moretz’s performance and its collateral effects on the whole film, but I’ll stop. It sounds like Moretz is evaluating her professional future at the moment, anyway; I would propose that she needs some formal dramatic education if she wishes to continue in film roles of this depth.

Gerard Barrett attends the ‘Brain On Fire’ Premiere during the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival at Princess of Wales Theatre on September 16, 2016 in Toronto, Canada. (This is the night before I saw him; at my presentation he spoke without the podium.)

So if I’m this critical of Moretz’s performance, why am I relatively sanguine about the film’s future? Most of it relates to Barrett’s statements in the Q&A. As a side note — I often found myself smiling at his Irish-accented English. He kept saying “fillum” for “film,” “tings” for “things,” and “thrace” for “trace.” And there was one really cute moment where he said “Jaysus.”

I learned this morning that Barrett wrote the screenplay (previously I thought he had stuck with a screenplay given to him by Charlize Theron). That discoverywas admittedly a bit disappointing. Still, to me, almost everything about this film is explained by statements Barrett made in response to audience questions at the end of the showing. To wit (paraphrasing from notes):

- His involvement was truly last minute — about only four months from being contacted to shooting it; they did only three weeks of prep; they did practically no rehearsal of any scenes; and they shot it in sixteen days in Vancouver and one day in NYC;

- There was little experimentation while shooting, and practically everything from the shoot made it into the film; the goal was an adaptation of the book that presented its most relatable moments;

- Because the film needed to be accessible, he decided not to “hijack it with his creative vision” (direct quote);

- In making the film — which he felt was important, that it was a movie that needed to be made — he “put aside the evolution of [his] directorial career” and decided the film didn’t need any “point-of-view bullshit”;

- He intentionally did not want to revisit the question of how illness in general is portrayed on film;

- He felt that they did make filmic sacrifices in order to make sure the film was understandable.

His comments more or less overrode my initial reaction that the first half of the film should have been written entirely differently. Since we know that Cahalan doesn’t remember most of these events herself anyway, I would have suggested a more perspectival emphasis on who noted what about Cahalan’s behavior when — something grittier that asks more questions about perception itself, possibly incorporation of more of the closed circuit video material — although this approach potentially could have required an even greater amount of performance flexibility from Moretz, which admittedly I do not think she has. Barrett must have known that Theron would try to attach a very high profile young actor to the project for publicity reasons (initially, it was Dakota Fanning), and that he wouldn’t be able to count on directing someone with extensive dramatic training or have any time to get the actors to acclimate to each other.

In other words, since Barrett didn’t intend the film to reflect on him as an auteur, and it is definitely not a made-for-tv weepie, Barrett’s remarks make it clear that Brain on Fire is definitely a “message” film. Barrett stated over and over again that the point of the film is to be “accessible” and that viewers should be able to see it and ask doctors if a sick relative has anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. He referred to the case of a hospitalized patient in the UK known to him right now in which the family is trying to persuade the treating doctors to explore this diagnosis. He asserted that people needed to see what the symptoms of the ailment are clearly and simply, and to understand that the doctor must start by applying the correct diagnostic tool (the “draw a clock” test — that coincidentally, those who watched the first season of Hannibal saw Will Graham perform — I wondered if the scriptwriters had read the book).

Barrett stated that he and Theron are determined that the film will achieve worldwide distribution. Given that there are several foundations and non-profits now concerned with the issue / message of the film, it seems that there will be many semi-public screenings for the issue of awareness raising (no matter what). While it may not go straight to television, there is no question in mind that it will eventually get there, and also that the people involved will not let the film rot in a can but will eventually enable streaming. For Cahalan, Theron and Barrett there seems to be too much at stake on the level of the issue simply to let go of it, and Cahalan has proved that she has not only the energy to recover from a frightening disease, but also to write a book and get the book turned into a film.

The makers are going to have to protect the interests of their investors, first, and they will definitely go the traditional route. But I don’t think they are likely to be deterred by the usual obstacles. And the film is of a quality that it will sustain distribution. It is not artistic. It was cast with the wrong lead (albeit it with good intentions of increasing audience). But it is clear and coherent, a story powerful enough to affect the viewer without degenerating into pathos.

[OK. 3200 words. I still have detailed notes about Armitage. I need to have lunch and watch my nieces’ volleyball games but look for installment two, focusing on Armitage, this evening.]

Continues here.

~ by Servetus on September 19, 2016.

Posted in Richard Armitage

Tags: Brain on Fire, Gerard Barrett, Richard Armitage, Susannah Cahalan, Toronto

43 Responses to “Review: “Brain on Fire” #richardarmitage (Toronto trip part 1)”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Thanks. Looking forward. By now you’ve seen some other reviews but I doubt they will sway you, though I will note that some podcast reviewers thought this was a very difficult film to watch because of the patient’s various acting out. .I’m thinking we’re going to read good things about Richard Armitage, and I know we’re all delighted that he has a bigger role than we anticipated. I still think that to raise awareness of this disease, money would have been better spent on educating health care professionals through seminars, conferences, journal articles. But I like your thought that somehow sometime, we may all have a chance to see it.

LikeLike

Warning: this comment includes my political reaction as well as my artistic one:

I absolutely agree with you about the greater relevance of educating health care professionals as opposed to making a feature movie. There’s an uncomfortable (for me) tinge to this entire project, from book to film, of white upper middle class privilege, of an “it’s not fair that this is happening to me!” (an impression unfortunately exacerbated by Moretz’s aura of entitlement while playing Cahalan and the way her parents behave in the film in response to doctors who disappoint them). The Ca

I don’t want to suggest that a diagnosis is unimportant to someone who is suffering; obviously most ill people want to be cured and I share in that wish for them. But on that level, the significance lies in the fact of the cure but not in the matter of who specifically is cured and an autobiographical project on that basis takes huge rhetorical risks of seeming narcissistic. In the end, this disease is not really statistically significant. The movie included a postscript that before her diagnosis, only 217 people had been diagnoses with the disease but more than a thousand since. That’s five times as many as before but we’re talking about a thousand people in seven years, which is hardly an earth shattering number, given that 51 million people (1.1 percent of humans) are thought to suffer from schizophrenia. Apparently people were studying this disease before she got it and have continued to since her book, and the result (acc to something I read in The Lancet, assuming I understood correctly what I read, which is often a risk in medical journals) is that a small proportion of people who have schizophrenia or psychosis also have NMDA-receptor antibodies. I.e., most people who have these illnesses at present were not victims of encephalitis. The doctors studying these populations have thus suggested tests for NMDA-receptor analysis only for cases of new-onset psychosis and primarily if the patient was suffering from viral symptoms beforehand.

I’m sure that the book (and by extension the movie) have helped some people who might otherwise have gone undiagnosed, and to those people this help is priceless. At the same time, however, the form and sheer volume of this crusade suggests that this is not Susannah Cahalan’s only focus.

LikeLike

Much of what you wrote was my feeling when I read the book and i wrote about it. It’s dicey to criticize people with serious illnesses – and that’s not what I want to do, but I go back to the point that this person suffered for one month, and I think about the millions of people who have life-long struggles, and with diseases that have no real cure. I think it might be a fluke for a patient or friend of a patient to rely on this film and then educate their doctor to look for this condition. (Though, I read that it did happen – oh, from you) Of course, for stating this position, I was criticized on the chat during the live press conference by a certain, well known cheerleader of everything Armitage.

LikeLike

Supposedly, the book has had that kind of impulse, but it seems that this particular disorder was already on the radar before the book was published (how else would SC have been diagnosed?).

LikeLike

P.S. Many New Yorkers would definitely assist or inquire if they saw someone in need or distress – I can attest to this personally – OTOH, in subways an stations, we tend to ignore more bizarre behavior. Still, your point is accurate.

LikeLike

I haven’t had the experienced but I assumed so.

LikeLike

Of course. We may walk past a dead body, but anything moving, we help. As I said, strangeness on the subways is more often ignored because mentally ill homeless hand out there sometimes.

LikeLike

Interesting review, and while not wholly positive, is far more insightful than yesterday’s snarky Variety review. I get what you are saying — there is a huge maturity gap between 18 and 24, and even an actor who has through career choice probably had to mature early might have trouble pulling it off. Being convincing without being cartoonish when portraying mental illness is incredibly difficult.

Your director’s comments seem consistent with my memory of this. We heard of the movie, and then almost immediately they were filming. This was a film that was going to get made one way or the other and needed to appeal to a broad audience, and it sounds like they more or less achieved what they were trying to do. That back story makes a big difference in your assessment, but does not seem to be taken into account by other reviewers who are treating this as a regular film. But if the goal of the filmmakers is to get the film out there, then they will find a way.

LikeLike

I’ve spent a lot of time with 18-24 year olds, so I asked myself if I’m party to experience that others don’t have (i.e., I may be an atypical observer). But I just could not get past the fact that even at the beginning, she doesn’t seem to be the person Cahalan was in 2009, before all this happened.

I do think that the filmmakers want the film seen as a regular feature (presumably they attracted investors on that basis), or they wouldn’t have brought it to TIFF. The best strategy would be wide distribution. But if they don’t find it, I doubt they will leave it at that.

You know, in the end, with the exception of Moretz, this film was not any worse than plenty of films I’ve seen in the theaters — it’s all a matter of who will buy it. Who knows — maybe Chloe Moretz has a huge fan base in China, for instance.

LikeLike

oh: I just read that review, and while they are correct that Moretz doesn’t do well in this role, I thought the point about the film being too earnest was a little odd. It was like they wanted the film to be snarky, too, or it wouldn’t be convincing. They also had a really different read on some of the minor plots and relationships points in the film than I did — but whatever. Half of the reviews I read these days, I wonder if the reviewer actually saw the item they are writing about.

LikeLike

Nice review, Serv, and as we had some discussion after the film, I must say that you have summarized some of our initial thoughts really well. I suppose one has to keep in mind that this film was clearly made in a hurry, and that there was no time to stop and consider what was “working” or not. I won’t reiterate all of the things said about Moretz, but I have reflected a bit and think that portraying mentally disordered behaviour requires a skill set far beyond her abilities. I imagine it might be one of the more difficult things an actor could be required to do. I am perplexed that nobody in that business would have realized that she was ill prepared for that role. The first half of the film, where we see episode after episode of her bizarre behaviour, actually became a bit tedious for me as a viewer. Some scenes made me cringe a bit. This was partly because she did it in pretty much the same way each time, and there was not very much buildup in suspense (which could be a script issue, I suppose). Once she was in the hospital, and there was less focus on her and more on her family connecting with the doctors, I felt that the film improved (and it is no coincidence that this also was the point where we saw more of her parents!) But I will not steal your thunder and await your observations of Armitage in the later installment.

It was a pleasure spending the day with you! 🙂

LikeLike

Oddly, we did talk less about Armitage and more about the film, but i think we were both overwhelmed by the power of the face. So I’ll look forward to your comments on the next post.

I don’t know if that stuff excuses the film, but it does explain why it took on this form. I assume that most people involved in it were looking for networking of some points — Gerard Barrett wanted to work with Theron; Armitage wanted to work with Barrett, etc. The question is what about this project attracted Theron so much. We talked about the networking advantage you have as a reporter for the post. I was just looking a bit at the Cahalans, and they are fairly well known. SC’s mother was quoted in the NYT in the 90s about fairy tale reading for kids; TC had quite a high powered job in banking and seems to have left to become a banking consultant. They probably have connections all their own to help their daughter with.

LikeLike

The book seems like a natural thing to me. She is a reporter, had a unique, life-altering experience, and decided to write a book about her story. She probably had the connections to get it published. She just needed a convincing reason for the publisher to believe it would sell. And it has been a bestseller, so this can all be explained more or less as a business/career move more than a political one.

I suppose the question is why make a film about this? Is there a broader message intended to go beyond the particular ailment of Cahalan?

LikeLike

I don’t think there is — if Barrett was serious about everything he said about “no POV bullshit” and not revisiting what disease means (along with the elimination of the comeback story, which would have added meaning to the piece and also extended it to a reasonable length — at present, it’s only 90 min long). To me, that was weird, because a hugely important point of creating anything artistic is POV. One goes to see a director’s movies precisely because of hIs/her POV. But he kept saying, no, this is only about making this disease comprehensible / relatable / accessible.

(I also think it’s not possible to make a film without POV. Because he’s not adding his, there are certain elements of the book that creep in that more or less occupy that same space — e.g., Cahalan’s apparent conviction that much of the US medical establishment is incompetent).

LikeLike

Thank you for this very interesting review. That Moretz just isn’t well-cast since she lacks the experience to give a convincing performance explains quite a few of the other reactions / reviews. Unfortunately, that’s pretty common. All too often roles go to big names and not to more talented but lesser known actors. It’s generally not good for the films in question.

With regard to the film’s purpose I had the impression that it’s very important to those involved in its making that regular people can recognise what might be wrong with relatives, friends etc. so they can then find help. Cahalans doctor also clearly stated the problem that a lot of doctors don’t take the time to actually listen to their patients or simply feel that they are too far above them to bother with that, because after all, what do patients know. Having suffered from long-term health problems that were exacerbated by several specimens of just that kind of doctor (and the resulting misdiagnoses and wrong treatments) and my relying on them / not knowing enough to help myself, I would agree with Barrett that this is very important, even if it doesn’t concern as many people as other diseases. Maybe even more because fewer people know enough about it. So Perry’s idea to educate more people in the medical field is definitely important, and Doctor Najjar seems to be doing exactly that. But it’s definitely helpful for patients and their families to know something themselves and to be less dependent on doctors.

LikeLike

I’m not a huge fan of medical doctors (I won’t go into the whole morass of that topic at the moment), and I agree that they are often likely not to listen very closely (although I don’t think this differentiates them from other professionals, just that in this case, listening is really important).

In general I agree that patients should educate themselves; the problem in the US is that they often fill their arsenal with pseudo-knowledge. I think about this a lot insofar as it’s often the case that when I have a particular physical problem I google to see how serious it is and whether I should be worried. But I’m a fairly sophisticated consumer of information and I can read and understand at least certain aspects of medical journals. I can’t blame medical professionals for thinking a lot of the stuff that people read and then say to them is hairraisingly false.

LikeLike

Thanks S for the interesting review, better than i expected given the shortage of money, time and preparation. Sounds like it gets the message across effectively, which is all they seemed to want to do. I think artistically a lot more could have been done but then the start idea would have had to be different and a whole load of preparation would have needed to go into it.

I guess the best outcome would be for it to make some difference in awareness about the disease and mental health in general.

I didn’t expect it to be important from an artistic pov in the career of anyone involved.

Gives me a ‘fair enough’ feeling about it. There was no alternative project given the amount of time so i guess, why not.

Screen Daily seems to agree it is probably destined more for TV but they weren’t particularly taken with RA either.

https://t.co/Wn0shZEN3T

Given exposure i am not particularly bothered either way.

LikeLike

Yeah, I could definitely have seem more of an “art” film coming out of this, but Barrett would have had to embrace “that POV bulshit” and I think the money was simply not there. The first half of the script would have had to go through a lot of iterations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on gpg44blog and commented:

thanks for such a detailed insight x

LikeLike

This is an excellent explanation of WHY the film doesn’t work well. That is the thing that was definitely lacking in previous reviews, most notably the snarky Variety. It seems obvious that Chloe would not have been mature enough to pull the role off, and even her name wouldn’t seem to have met the objective if it was awareness, and not a large, young audience. Confusing. It sounds like the whole thing may have run more smoothly if Barrett had taken advantage of the insights Susannah and her parents could have given.

LikeLike

I come out of the tradition of academic book reviewing, which has certain conventions not followed in press reviews, obviously — but I don’t see myself overlapping with those reviewers except in the matter of saying “who should see this film.”

Susannah was on set the whole time — so I don’t know. She must have been involved.

LikeLike

This Variety review is just sub-standard IMO. I’m not familiar with it’s usual journalistic practice and style, but I simply abhor rhetoric such as it is presented in this review of Brain on Fire.

The artistic execution of the main character may be poor (I’ll take your credible word for it, Serv), but to call the main character’s real life events “laughable” and “an embarrassingly earnest film” (embarrassingly earnest – apart from the alliteration, I fail to see how those two words correlate). If the book is as close to the actual events as is expressed by you and other reviews, Variety disgracefully belittles a serious disease to which the film could potentially help raise awareness. Sad, that 😦

In conclusion, the review may actually prove a point. I’m protesting the means by which it chooses to do so.

LikeLike

I agree — “laughable” and “earnest” only jive if the reviewer laughs at earnestness.

I think it’s fair to say there have been lots of great films about illness / mental illness that are more artistic and potentially more sensitive than this film — but that could ahve been said without taking up the snark topic. Presumably most of those films are also earnest.

LikeLike

[…] from here. Sorry for all that background, but I needed to establish the larger parameters of the film in […]

LikeLike

Richard Armitage in “Brain on Fire” — evaluation (Toronto trip part 2) | Me + Richard Armitage said this on September 21, 2016 at 7:30 am |

Thanks for this, Serv! The impression seems to be prevalent that Moretz may not have been the right choice for the role… Look forward to the second part of your review (which I see is up now but which I will have to read later).

LikeLike

Glad you had a good time in Toronto and you had a good exchange rate. (I will not be so lucky for New York 2.0 if this keeps up.) I saw Moretz in Kick- Ass (both of them) and If I Stay. (The latter involved wine. Don’t watch movies on HBO Canada while drinking, you’ll never know what will happen.)

She does need training or a teacher to push her skills. The Harry Potter cast had the benefit of being around actors like Gary Oldman, an experience Daniel Radcliffe likened to attending a drama school. CGM has acted from age 7 on and she’s wise to take a step back to evaluate her career. Kirsten Dunst did that and it served her well in her recent work. However, that Variety review has the hallmarks of high-level shade and I can’t see an actual review they way I can see one here.

LikeLike

My hostess was so kind as to provide for me in situations where I would have needed Canadian dollars, and I was able to arrange the trip not to have to buy gas there, so it was good — this was one of the cheapest trips I’ve ever taken for this kind of thing. The only (minor) annoyance was the border crossing.

I can’t judge whether she could be more effective or not — I haven’t seen her in anything else. I tend to think she has a kind of “rom com” sort of appeal; her look is not rugged enough to suggest that she should be cast in meatier things. But I also seem to remember that at least some of the HP cast took acting instruction during filming breaks, no? I thought Radcliffe had.

LikeLike

A few of them did. Don’t recall who amongst the sprawling cast of young people.

LikeLike

Sorry to hear about the border crossing. 🙁

LikeLike

it is how it is … and it’s nothing like the chaos of the situation on the southern border, so there’s that. But I did find myself thinking hard about the purpose of borders at that point. The Canadian agent (going) was suspicious that I was going to meet someone I hadn’t met and the U.S. agent (coming back) didn’t believe I’d drive to Toronto to see a film. ??

LikeLike

They obviously never heard of TIFF.

LikeLike

I thought it was weird — there must be plenty of people who drive over. Maybe more in Niagara than in Sarnia, admittedly.

LikeLike

I got used to my car getting searched after shopping trips to North Dakota.

LikeLike

for … drugs? cheese?

LikeLike

Yes on both or if I am trying to take clothing or items not declared to avoid duty. Although, I did know people who bought a lot of cheese and yogurt. Those Yoplait flavours you can’t get up here.

LikeLike

I admit it’s hard for me to think of dairy products as contraband, but this spring I read an article about some trucker who’d smuggled $700,000 worth of cheese in. In a way, it’s nice to know what people will do for yogufrt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We not talking just any Yogurt. Keylime pie was a popular choice. I go for the fashion. At least items not seem up her. Oh, and shoes. Been a long time. I prefer Fargo to Grand Forks. I bought a couple of items in New York.

LikeLike

As always your views are spot on. With regards to mental illness you are correct with most you tend to be aware of a lot of what is going on and try to hide it. I have had two Autoimmune diseases which did affect me mentally at times and one gave me schizophrenia and hallucinations for a while the other dementia where I thought my husband was trying to “gaslight” me. Yes, there are parts that read like a bad soap but I have no desire to write a book.But somehow you know deep inside of you there is a reality you are not touching…I can’t explain it, but it is there. I hope this makes sense, even though I am now my “normal” self.

LikeLike

I think that’s a useful description — thanks. I’ve never hallucinated, but just lately (time of life) I’ve been more aware of how much body chemistry affects not just one’s moods, but one’s responses in certain contexts. We all do need to be more aware.

LikeLike

To the person who attempted to post the comment about mental illness — you know who you are: At present, I am not prepared to post comments from individuals who egged on and contributed actively to the harassment campaign against me in Fall 2013 and spring 2014.

LikeLike

[…] review is in two parts — here on the strengths and weaknesses of the film and Chloe Grace Moretz’s performance and here on Tom Cahalan as a character and Richard Armitage’s […]

LikeLike

If you’re watching Brain on Fire with Richard Armitage just now … | Me + Richard Armitage said this on June 6, 2017 at 2:33 am |

[…] 2014 (the others were Sleepwalker in October / November 2014; Pilgrimage in mid-spring 2015, and Brain on Fire in August 2015). When this project was announced in March of 2014, there was a huge sigh of relief, […]

LikeLike

Richard Armitage in Urban and the Shed Crew, first reaction [some spoilers] | Me + Richard Armitage said this on April 9, 2018 at 8:39 am |

[…] by liquid sunshine. The first night I was supposed to see him, The Crucible got rained out. When Babette and I went to see Brain on Fire at TIFF, it was pouring, too. It was humid and rained several times in NYC during my Tribeca Film Festival Pilgrimage […]

LikeLike

me + Richard Armitage + rain, or: A whole post to say I’ve decided to buy new shoes | Me + Richard Armitage said this on June 17, 2019 at 10:49 pm |