Love, Love, Love: Attempt at description, Act 1 [spoilers] #richardarmitage

[SPOILERS!

- I’ve never written a post like this before. The purpose is to try to document what happens in the current performance of Love, Love, Love as I saw it from 11/3-11/6/2016.

- The post is over 8,000 words long and took about ten times as long to write as it did to watch the act. So you may want to break up your reading of it. I apologize for the length; the goal was something as detailed as possible.

- Since the production itself is copyrighted, the point isn’t a summary of the content or a comprehensive description of blocking, etc. (which I doubt I could provide, anyway; my memory isn’t sufficient and those are not the kind of notes I usually take on a performance). Rather the goal is to give someone who hasn’t seen the play an idea of what it is like to see it, or a notion of what one does see. I sketch out the plot, but do not cover individual lines in detail except as I consider them especially successful, exemplary, or problematic.

- I know that some things have changed since the beginning of the play — and perhaps since I saw it as well. I didn’t get to see Armitage vault over the sofa! It’s hard to write a permanent description of something that only takes place temporarily. If you saw something different, feel free to comment in the notes.

- The play as performed is not quite the same as the script from 2010 (which I read) nor as the script from 2015 (which they were selling in the theater).

- I will try to give an indication of lines that are played for laughs, but in my viewing of the play, the audience laughed in different places every night, although more so in Acts Two or Three than in Act One. And some lines that I thought were intended to be funny flew right by the audience either most of the time or every time.

- In general, I found that concrete jokes and references that would have been intelligible to an audience in the UK were downplayed in this production. I will indicate when this happened because I think it’s significant to how the American audience might perceive the play differently than it was received in England.

- I’m no judge of UK accents and don’t intend to venture on to that terrain in any detail. I’ve heard opinions in both directions from people from the UK who’ve seen the play about the English accents of the American actors and so can only conclude that one’s judgment depends in part on where in the UK one is from and how particular one is. I will say that I found all the accents sufficient for their purpose, i.e., to convince an audience of New York theatergoers that the actors were members of an English family. I didn’t find myself constantly thinking “that doesn’t sound right.” But I’m an American and haven’t spent huge blocks of my life in the UK, either.

- Also, this description will include some interjection of opinion / perspective from me.]

***

Love, Love, Love (2010) is a dark comedy or perhaps satire of manners about a twentieth-century couple, Kenneth and Sandra, and their two children, Rose and Jamie. Kenneth’s brother, Henry, also appears in Act One. The play reveals the three generations (Henry, born before the end of WWII); Kenneth and Sandra, the baby boomers; and the children, Generation X) in conflict with each other, and shows the outcomes of this conflict. Kenneth and Sandra meet at Henry’s apartment in 1967 when they are nineteen (Act One); they have children in the 1970s and then experience marital troubles and divorce in 1990 (Act Two); and finally meet again in 2011, after Henry’s funeral, when the audience observes a final “family conversation” (Act Three). Each act runs about thirty-five minutes with ten-minute intermissions between them. While the subject matter may be serious (as it is here), in this genre, typically none of the characters are invested with significant emotional depth, because the play presents a social snapshot of a situation it seeks to satirize rather than presenting the personal development of the characters. Plot is less important than dialogue, because the dialogue prioritizes showing the audience how the characters appear to us and each other rather than how they change. Thus plot in such works can appear meaningless or (as in this case, depending on your perspective) implausible or silly. This effect is intentional as it is meant to clear space in the audience’s mind for thinking about the significance of the social snapshot on offer.

[I’d meant to have written by now an analysis of how Mike Bartlett’s plays that I’ve read are typically structured, but it will have to wait for now. The punchline would be that his general strategy is to force irresolvable philosophical positions or political interests into head-to-head conflict and see what this dialectic engenders in the interactions of his characters, but without taking an obvious side or resolving the conflict; sometimes this strategy results in a facile work (as, in my opinion, in Wild), but it is quite productive in Love, Love, Love.]

Here goes.

BEFORE THE SHOW

The audience walks into the theater and is treated to a playlist of songs from the 1960s. Many audience members listened to this music as children or in school and are singing, humming or tapping along with it. The mood in the theater is quietly positive with a lot of conversation going on. The audience can see the very spare set for Act One, which is set in Henry’s apartment. A few minutes before the play starts, Richard Armitage’s voice asks everyone to turn off their cell phones. The house lights fall, the music fades, and the audience quiets down.

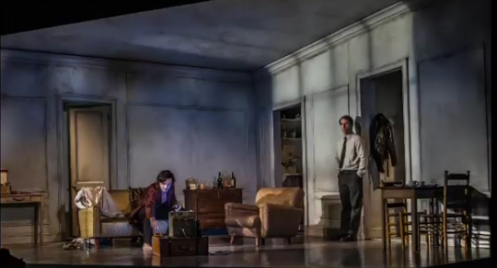

Photo from side of theater (stage right) on opening night, courtesy of @DaphneHS. Kenneth (Richard Armitage) will enter from the door on the right of the photo, which seems to go to a bedroom or other rooms. The door in the center goes to the kitchen, and the door on the right is the entrance / exit of the apartment, from which Henry and later Sandra will enter. The brown chair appears to be “Henry’s” chair. On the right margin of this photo you can see Henry’s dining table, which is covered with dirty dishes. On the left margin of the photo is a table with a phonograph and some 33s. And behind the yellowish sofa is a cabinet / sideboard of some kind with several bottles of alcohol on it. The suitcase in the center has a television (a model I’ve never seen in the U.S., with volume / on-off switch and tuning on top) on it, and an ashtray. The floor is covered with used clothing and more dirty dishes and glasses.

ACT ONE

Kenneth (Richard Armitage) enters stage right; he’s wearing woven brown trousers and a flashy red “housecoat” (incidentally, Ben Miles wore a similar one in the Royal Court production of the play) with no shirt under it. The coat has a sort of “Oscar Wilde” / “rules don’t apply to me” vibe. He’s barefoot and his feet appear huge and flat. First he peeks through the door, then he scoots around the apartment — looks into the kitchen, pours himself a glass of brandy (or something brown), settles in the chair to watch the television, lights a cigarette, then thinks better of his place and moves onto the sofa and sits up straight. Eventually he settles.

Source. I’m going to use this montage vid to illustrate, but remember that Kenneth’s haircut has changed since these shots were taken.

This is really comical and he gets a lot of laughs — He has a very excited expression on his face, and Armitage mimics a little kid sneaking around and captures the way that little guys sort of thunder around a room with his motions and gestures, although he is light on his feet. He’s watching this and the Vienna Boys Choir is on.

Just after Kenneth moves onto the sofa and improves his posture, Henry (Alex Hurt) enters from the exterior. He’s wearing dark trousers, a grey shirt, a dark striped tie, and a black leather jacket. The two men are in strong contrast — Kenneth is tall, lanky, relaxed and barely dressed while Henry is short, stolid, a little bit hunched over, and has an air of tension. Henry takes off his jacket as Kenneth tells him he’s late and the dialogue begins.

Kenneth thought Henry wanted to watch the “Our World” program and Henry points out that he had to work and doesn’t (dig!) get a free ride like “some people,” i.e., Kenneth. They begin arguing in the style characteristic of their interactions, very rapid fire, often not letting each other finish before starting the next line (this is indicated in the older script I have, but not the newer one). Henry’s accent is working-class (for Americans reading this: not Cockney) and his speech is loud and heavy (although Hurt’s pronunciation of consonants isn’t entirely internally consistent — yes, I spent a fair amount of time considering the status of his alveolar flap). Kenneth’s accent to me sounds like it’s in transition — not as noticeably “working class” as Henry’s but still with signs of his non-Oxford origins. (For instance, Kenneth says “wiw” for “will”.) Their first point of argument is Kenneth’s insistence that Henry could get a scholarship, too, vs. Henry’s resistance. Then Henry sits down in the chair and they watch tv (technically telly, I suppose, although Kenneth says “television”).

Kenneth explains what’s on and why it’s important as Henry grows more impatient. Eventually, Henry asks Kenneth what’s on another channel (this dialogue is changed from the script, which assigns Henry an expression that American audiences would not understand) but Kenneth ignores him. Henry takes one of Kenneth’s cigarettes. Another one of these rapid-fire conversations ensues once Henry asks Kenneth if he’s been outside. The pattern in all of these conversations has Henry on the offensive and Kenneth backpedaling; this time they bicker about whether Kenneth has purchased anything other than beans for the apartment (bog paper, they use the British expression; butter; milk). It ends with Kenneth crouching defensively in his place on the sofa, insisting he was only following orders. (Armitage played this in two different ways as I saw — more frequently with Kenneth cowed, but twice with Kenneth annoyed — although the difference is really subtle). How they do it is really funny and these over-each-other conversations got lots of laughs every time I saw the play.

But Henry is the stronger partner in these exchanges and Kenneth knows it. Henry says, in a deliberate, insinuating tone, that it might be time for Kenneth to move on. Hurt’s tone is so full of indignity that it’s funny. Armitage doesn’t play Kenneth frightened here but still very tense — we can tell he doesn’t want to go and he’s trying to figure out how to de-escalate. There’s a moment of calculation on his face. He decides to ply Kenneth with liquor and stands to pour him a glass.

Kenneth walks stage right behind the sofa after Henry accepts the glass. It’s at this point that we first learn that the two men are brothers, as Henry mentions that their father has called him that day at work to clarify where Kenneth is spending the summer, as a letter from Kenneth has arrived that has concerned them. They agree that dad has his mad moments (he speaks differently on the phone, “like the queen or something,” possibly because he believes that he is being overheard). Kenneth’s mother thinks he’s been kidnapped and Henry wants Kenneth to call them. (Implication: from a phone booth — it emerges that Henry only has phone access at work and will thus be subjected to further unwanted parental contact if Kenneth doesn’t get in touch.)

By this point, Kenneth has crossed almost all the way stage right and is standing to the side of the sofa as Henry returns to the insinuating (and funny) suggestion that Kenneth go home. Kenneth is not having this and he sits, his rear on the floor, drumming his legs, almost like a tantrummy three-year-old, to refuse, noting that they want him home but when he’s there, they ignore him. Laughter. He looks fit to work himself into a lather when Henry informs him that they thought Henry knew where he is. Kenneth perks up his head at this and inquires what Henry said. Henry tells him that he said he hadn’t seen him, and Kenneth responds in relief that Henry’s a true brother. Laughter. But Henry also says he thinks Henry should be giving some of his grant to his parents (he makes in grant money what his father makes, working hard) and Kenneth rises to his full height and sticks his chin out, insisting that he’s the future of the country. Henry points out the money comes from his taxes.

Henry seems so tense, leaning forward, his hands clenching. One of the successes of this play is that we laugh in recognition all the way through interactions that are fairly tense, I think because anyone who has had to deal with a sibling recognizes this sort of “sniping with history.” Their relationship is very (for lack of a better word) human. In general, Henry gives off an aura of simultaneous fatigue and readiness to explode. They both seem to realize that they are on some kind of precipice, and again Kenneth is the one to resolve the status conflict. After a moment of silence, he tells Henry that he’s grateful to be able to stay with him and that going home (with the return to sober manners) would be like prison. He’s now pacing back and forth behind the sofa, adopting the tone and gestures of an idealistic undergrad pontificating about the boredom of the world. Henry suggests Kenneth get a job and Kenneth replies that he’s supposed to concentrate on his studies because of the grant — a statement that Henry repeats with serious sarcasm. The question about how Kenneth gets his money is batted back and forth often in this scene and gets laughs every time. Henry suggests that Kenneth could hang out with friends from school, and Kenneth responds that they haven’t changed.

At that point, Kenneth sees a point of rapprochement and points out that Henry understands, because he, too, came to London. Henry has now moved to stage right while Kenneth has circled around to the center of the stage and is standing near the television. Kenneth exuberantly lists the advantages of London, starting with the fact that things actually happen there, and moving on to architecture, music, style — and especially “the birds.”

Henry agrees on that point. And then Kenneth says (p. 28): “Even bloody Harold Wilson. Saw him the other day. He’s smaller than you’d think.” This is one of those moments — it’s almost inconceivable that 99 percent of Americans would get this joke. Wilson was PM at the time of Act One, but everyone I know in the U.S. who could tell you who Harold Wilson was is an academic and that’s the only reason I know, myself. But they left it in, and Armitage’s tone is hilarious. He sort of cocks his head to the side after “the other day” and then raises his tone for “he’s smaller than you’d think” and looks bemused / reflective. This is fall-down funny. I was the only person I ever heard laughing at it, though. This raised tone of voice is part of Kenneth’s bag of tricks for annoying his brother.

(This play omits the detour in the script about the World Cup and the explosion of the parents’ television.)

Now the two have moved on to the topic of “birds” (just in case, noting that that is twentieth-century British slang for “women”). Henry is still at far stage right and Kenneth is now sitting in Henry’s chair with his legs tucked under him.

Henry starts to suggest that there are a lot of “birds” in London [just in case: twentieth-century British slang for “women”] and Kenneth must have a friend and so on, and Kenneth clocks that Henry wants him out of the house. Henry, at extreme stage right on the edge of the proscenium, is staring out into the theater and says, in a tense way, “well, not to put too fine a point on it.” Kenneth asks the bird’s name and Alex says, in the same challenging tone, “not your business, is it?” The dialogue is so quick in this play that the viewer doesn’t get a lot of time to think, and that’s intentional, but thinking about this now, I wonder if a non-comedy version of this play would imply a backstory here of the older brother always feeling disadvantaged by the younger, a tension that’s also written onto the relationship between the “silent generation” as they are called in the U.S., Henry’s tribe (he was born in 1944) and the boomers (Kenneth was born in 1948).

Henry wants him out of the apartment. But Kenneth is settled in the chair with cigarettes, ashtray, and drink, wrapped up in his housecoat, and says, in a cheeky tone of voice, “I’m settled now.” Armitage has his feet on the floor by now and he lifts his rear out of the chair and sort of shimmies from side to side, wiggling his ass, to express his snuggled up comfort. Uproarious laughter.

[Editorial comment: seeing Armitage do this kind of physical comedy is both surprising and hilarious — it’s really several degrees more complex than his comedic moves in Vicar of Dibley and he really seems to be enjoying it and the attention he gets on stage. It feels mildly astonishing as I don’t think of him as an actor who mugs to be noticed, but he mugs like crazy in this scene. He plays the annoying little brother for all it’s worth and exaggerates every dig Kenneth makes at Henry with a physical flourish of some kind. Just seeing this addition to his skill set alone made the trip worth it for me.]

The topic becomes Kenneth’s “housecoat,” which is a bit over the top and generates another rapid-fire sequence of bickering between the brothers about whether Kenneth is queer (this moment is extended here in comparison to 2010, following the 2015 script). Physically, Armitage plays this a bit like the mole in a game of whack-a-mole: every time Henry says something to Kenneth, Kenneth twists his body, moves his head up or down, smiles enigmatically, or raises the tone of his voice. It’s like a flirtatious game of verbal keep-away. Uproarious laughter.

Kenneth tries to explain that the rules are changing (cough: “the walls collapsing”). Henry is bent on getting rid of Kenneth, though, and returning to his obdurate tone of earlier, pushes him to leave again. Now Kenneth claims he has no money. Henry has his back to much of the audience, but you can see him tensing up (and speaking as the older sibling myself, I’m on his side at this point). Kenneth says he won’t be in the way and then suggests Henry’s bird can bring a friend. Henry insists she can’t. Kenneth says they could “make up a four” and Henry says no. Kenneth, still tucked up in the chair with legs under him, reminisces about brothers from their neighborhood who went out in tandem and suggests maybe Henry and he should do that. (This section is cut significantly from both 2010 and 2015 with an entire paragraph omitted here.)

Kenneth is acting quite cheery, but in response, Henry crosses from front stage right, past Kenneth in the chair, and throws a bill into his lap, which he describes as “a few bob” (it has a pinkish cast — glancing at a page of historical British currency, it could be the 1966 ten shilling note but I wouldn’t stake my life on it. I hated “historical currencies” in grad school, but remember that a pound had 20 shillings and a shilling 20 pence till 1971. I was just looking around and seeing prices from 1967; a pint seems to have varied in price from 9-15p outside of London. This is a fairly generous gift for a night on the town. I’m not obsessive about historical detail in any way, no, not me). Kenneth cringes back into the chair, as Henry’s quite forceful, but then looks at the bill, grins, and pockets it. Henry moves on into the door that represents the kitchen when Kenneth asks again about the bird’s name. Big laughs.

This makes Henry angry, and he turns about and pushes Kenneth out of his chair, toward stage right. Big laughs again.

Henry follows; Kenneth is standing stage right in front / to the side of the sofa, Kenneth is facing him, and Kenneth says, now with real menace in his voice, “you remember the fights?” Kenneth crouches like he’s about to be hit, his eyes are wild in (mock?) fright, he pouts.

[Editorial interjection: it’s a bit surprising how this works insofar as Kenneth is supposed to be younger and Armitage is so much taller and clearly more physically imposing than Hurt — but it really does. It’s all done with voice, posture, gesture, and status games, but Henry consistently enforces his higher status as the older brother until the very last minute of the scene. In a way, it’s almost more comical to have them playing against body type, because Henry’s vibe is so tyrannical and Kenneth’s is so submissive, even as he is clearly manipulative. A little like laughing at a very angry mouse terrorizing a dopey but smarter-than-he acts elephant in a cartoon. Or: Henry swats a fly but the fly keeps buzzing. Blocking / acting genius and fascinating to watch.]

Kenneth backs off the status conflict again, puts some distance between them by moving far toward stage left, almost to the table, and convinces Henry to tell him the name: Sandra. Kenneth approves of the name. He then inquires about how long they’ve been doing it and Henry admits they haven’t, but this is the first night they could, so he doesn’t want some “spotty bastard cluttering up the place, wearing his queer fucking coat of many colours” (masterful line — uproarious laughter). Kenneth suggests that Sandra will be repelled by the disorder of the apartment and Henry stalks toward him again, pressing him back toward the table and into a chair at far stage left — physically towering over him as Kenneth cowers and promises to leave after he’s helped Henry tidy up. Again, lots of laughs at Armitage’s shaking.

Henry backs off and they start cleaning things up.

Kenneth’s idea of cleaning seems to be to hide things — at one point he kicks a sweater underneath the sofa and gets a lot of laughs; he smells one of the dirty dishes on the table and grimaces. Henry is more comprehensive; he brings things into the kitchen and at least twice retrieves and puts right the mess that Kenneth tries to hide. As they clean they start talking about Sandra. Kenneth’s position is that Sandra is gorgeous and has huge knockers (twentieth-century British slang for breasts) and this makes up for the political nonsense she spouts. Henry gets laugh after laugh as he says various sexist things that were standard for the 1960s, a very mild form of “lads’ talk” about her breasts and legs. A big chunk of this is played with Henry standing on the threshold of the door to the kitchen and Kenneth stage right, behind the sofa. Kenneth listens to this evaluation and wonders if Henry’s shared it with Sandra. Henry says yes, and that Sandra called him a chauvinist. And then we get one of these viciously biting jokes that Bartlett builds into the script that have at least two purposes.

K: You said that to to her?

H: Might’ve mentioned it yeah.

K: What did she say?

H: That I was a chauvinist.

K: Bit unfair.

H: I know. I told her, I’m not driving anyone around, they can drive themselves.

[Laughter to bring down the house]

K: That’s not what chauvinist means [through laughter]

H: Bloody hell Kenneth you really think I’m a fucking thick bastard don’t you?

[Beat]

H: I know what it means.

[Mike Bartlett, Love, Love, Love (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 35-36. My italics.]

On the one hand, we’re supposed to laugh at Henry for not knowing the difference between “chauvinist” and “chauffeur” — and we’re comfortable doing that, at least I was, initially. Then it’s funny that Kenneth is so superior. But just when we’re laughing about that, Henry points out that he’s not that stupid, so the joke is turned back on Kenneth, except it’s not quite so funny this time. There’s a satire here of the working class, but also of stereotypical social views of the working class as exemplified by Kenneth’s reaction, at the same time. And somehow it’s still really funny — even though the second iteration is totally bitter.

Kenneth backs off physically and the tension and laughter recede. Kenneth asks about the time and it’s close to when Sandra will come. Henry expects Kenneth to leave but Kenneth wants to stay in his room. (Unanswered question: Is Kenneth hanging around so ostentatiously simply because it irritates the hell out of his brother and that is their standard interactive mode? Or only because it’s inconvenient to get dressed?) Kenneth promises he will go into his room as soon as she comes and reads (Armitage harvests more laughter for Kenneth’s description of his books: “you know, lots of words.” Henry tells Kenneth that even if he needs to piss he should stay out of their space. Big laughs for Henry, who tells him to piss out the window if necessary.

They are still straightening a little. Kenneth asks Henry if he hears from their father a lot. (This section is cut substantially from the 2015 script to omit discussion of their mother and a return to the theme of whether Kenneth is queer.) Kenneth has once again taken up residence in the chair. They agree that correspondence from their father is mostly coded language for “find a secure job, make money,” and each of them has a different resentments about that. Kenneth is offended that “civil bloody service” is the highest his father can aspire to for him.

Then Kenneth asks about Sandra and Henry gets a truly endearing moment when he describes, quite honestly, to his brother, how they met and how her attention makes him react. All through this scene, while I found Kenneth amusing, my own older-sibling sympathies tended to be on Henry’s side, and as he sits on the sofa, the two speeches that Henry gets (first, about how they met; then about how they arranged the date) are heart-opening. Important plot element: Henry has volunteered to cook although he does not know how, but they’ve arranged it that he will buy the alcohol and Sandra will bring ingredients and cook.

The conversation returns to Kenneth’s frustrations with his father’s attitude, and how he sees his own life.

I’m thinking that Roundabout gave us this moment in particular because it encapsulates the motive idea — but also the point of most likely betrayal — in the scene: wanting as the justification for everything, the rule of the new generation. But in any case, the brothers are really talking with and not past each other for the last (and almost only) time in the play.

Kenneth is cut off in his posturing by the doorbell. Henry tells him to go to the other room but Kenneth insists that he needs to meet her (more little brother scheming, the death of a thousand cuts for the elder sibling). They return to their physical skirmish of earlier, with Henry insisting that Kenneth get dressed, or at least close the housecoat — back to their posture in front of the sofa from earlier, with Kenneth standing threateningly while Kenneth pouts and then defensively ties the coat. Audience laughs after each line. Finally, Henry leaves to answer the doorbell — and Kenneth undoes the housecoat. Huge laughter.

He refills his glass, returns to center stage in front of the television and lights a cigarette, and poses artfully on the sofa. He’s trying to look — attractive? arty? intriguing? the kind of cool guy a bird will love? More laughter from the audience.

At two-thirds of the way through Act One, enter Sandra (Amy Ryan):

She is slight and is as Henry’s described her: well-dressed, has taken time with her hair (and Amy Ryan’s breasts are not that big but the period-accurate dress does accentuate their appearance. Henry grimaces to see Kenneth on the couch, shirtless, but introduces her nonetheless. Kenneth is definitely visually knocked out, and eagerly starts forward to greet her, correcting the introduction (“Ken”).

Sandra has a very self-aware bearing — she feels like she’s worth something and shows it (and I think that’s part of what Henry likes about her, frankly), she walks like an inspector come to evaluate or a queen come to receive obeisance. Kenneth describes her earlier as “posh” and she does speak in a way that implies slightly higher social class than the brothers. She has on a long-haired wig (accurate) and for reasons I don’t understand, extremely pale makeup that conflicts with the idea that she’s a late adolescent. One immediately thinks that she doesn’t look nineteen but made up to look nineteen, but I think there’s more of an unaddressed problem there (see immediately below.) She asks for a cigarette and Kenneth lights one for her as Henry takes her coat.

[Editorial comment: I will go into this further later, when I talk about individual nights of the play, and it has something to do with the tightly choreographed quality of the play, especially Act Two, but I felt like Armitage’s performances were very consistent all the way through this play. They fell within a particular range that had some variations and tolerances but was relatively narrow in comparison to The Crucible, where I felt like he was a motive force and had to make many more decisions while on stage. This is not a criticism of Armitage but a comparison of the characters involved. Kenneth’s primary character trait seems to be indolence and the not very active search for pleasure, and so his primary dramatic task throughout the play (until the very end) is to react to the demands of others, in particular, to Sandra, who makes all the decisions. I don’t want to say, he’s only as good as she is, but if acting is reacting, she’s the motive force in the play or at least the script suggests that she should be.

For this reason and because of some reviews I had read, I expected this to be Amy Ryan’s play and not Armitage’s. That was only pronouncedly the case on one night when I saw the play — Friday evening 11/4 she had a great night and got lots of laughs and the whole sphere of the play’s world seemed expanded. He seems to have a pretty consistent good night every night, but when she has a great night, he has a better one, if that makes any sense. I think I read an interview somewhere where she remarked that there are nights when the audience doesn’t like her, but I didn’t see it that way. There’s something problematic about her performance in Act One that I can’t quite put my finger on and it slows the play down. In any case, she’s best in Acts Two and Three, whereas Armitage is best in Acts One and Two. So to some extent, my remarks about her in this act will reflect my attempt to come to terms with my discomfort with her performance in it. Part of the issue is that at her entrance, she necessarily disrupts the atmosphere that’s been building for twenty minutes; in fact, that’s what is supposed to happen. But sometimes she entered lower-energy than the scene had been before she started, and that was a problem. Another issue is that the character makes a great deal out of her political and cultural attitudes and is quite egotistical, which is important to understanding why she attracts both men, but Ryan plays this with a variety of self-righteous mien that doesn’t feel quite goofy or loose enough for nineteen. I am having a hard time diagnosing the issue specifically, but I’ve spent plenty of time with self-important nineteen-year-olds who think they are no end cool and Ryan’s performance here just doesn’t make her seem nineteen. More like thirty. I think that Ryan could get over the fact that she doesn’t look nineteen if she behaved a bit more like she was nineteen, but perhaps I am wrong and British hippie nineteen-year-olds were like this in 1967.]

It’s noticeable from the point of Sandra’s entrance that she and Kenneth are drawn to each other immediately. Their stares are unabashed and Kenneth in particular makes no attempt to play cool. Armitage puts into motion a range of different emotions from straight sexual desire / smoulder, to giggly grinning, to something we might call “I like your style” admiration, to unsubtle flirting, and shadings in between these. If Kenneth might plausibly have been playing the little brother game and just been hanging around to annoy Henry up until now, at this point, he enters into a fairly open competition with his brother that he knows he has a good shot at winning.

Sandra points to him like he’s a statue and blatantly looks him up and down, gesturing with her hand as if he’s a work of art, to tell them that she likes his (lack of) clothing. The “dance” begins. She likes him because he’s decadent and says that Henry’s leather jacket is also decadent, like Joe Orton. Henry doesn’t know who Joe Orton is (and neither does the audience, frankly; I had to look this up after I got back to the hotel), but her immediately comeback upon that admission “or maybe not” has the audience in stitches, so that it doesn’t matter. Still, I think that a British audience might find this reference striking in a way that we don’t, because it has the whiff of scandal. Orton, one of the most notorious British playwrights of the late 1960s, was murdered by his lover in a jealous rage either contemporaneously with or very shortly after the events of this act. It was a huge scandal at the time.

[Also, interestingly for Armitage fans, Orton hailed from Leicester. So this theme of “boy who wants something big in the big city” connects not only Armitage and Kenneth but also this writer, cited as admired.]

Sandra feels the family must be decadent and Kenneth disagrees; they are boring. Sandra says this is why people come to London, but Londoners are in trouble if they are boring. Big laughs. I won’t give you the line by line recap, but big laughs here approximately every three lines, not always where I expected them to come — what you have to do to pick up the atmosphere is to read each line carefully and imagine where the joke is coming from, sometimes multiple jokes in a line. Sandra admits she’s from Essex (I wondered, were there the same jokes about Essex girls in the 1960s? or is that a more recent development?) and couldn’t wait to get away. Kenneth tries it on with the blatant compliment, saying in a rather foolish tone that he likes her dress. She pulls back slightly and leans against Henry, who’s leaning against the table (quite silently, as Sandra observes). As this conversation goes on, Henry twitches his jaw a few times at Kenneth but Kenneth isn’t taking the hint. They discover that they are both at Oxford (big play for humor with their sort of “undergrad incredulity”), but Henry did not know this (funny, but also embarrassing!). Sandra alternately pooh-poohs her connection with Henry and then pacifies him when he points out they’ve been going out for two months.

Sandra then proceeds to tell a story about why she’s lost her job. On nights when this is going well, Ryan can get up to three laughs per line, as here:

S: […] Last week I got the sack [she’s outraged, audience roars]

K: Did you? [a slightly astonished but fawning tone]

S: I’ve never had the sack before [if audience roars at previous line, then at the same level here] well I’ve never even had a job before [even more laughter] and I was outraged [most laughter]. All of a sudden they told me to leave.

[Mike Bartlett, Love, Love, Love (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p.43. My italics.]

It turns out she was smoking pot while waiting on a customer and these lines are hilarious to the audience at every performance I attended. As is customary in live theater, if people are laughing, the cast draws out the lines in order to enhance that energy.

Sandra suggests that she might have to come and live with Henry to make ends meet, but then asks if Kenneth will be around. Henry has gradually been getting more tense, while remaining silent, and now he finally verbally hints to Kenneth to leave. Kenneth complies, huffing and stomping his way across the room to the door with a big sigh and a very put-upon little brotherly attitude, but Sandra intervenes, wanting him to have a drink. Kenneth senses her interest and changes his vibe from resentful about leaving to reluctant to stay — he withdraws back into the door frame of the exit to the other room, but it’s a physical repeat of the earlier part of the scene, when Henry was hassling Kenneth about being “queer.” Armitage plays it standing in the doorway, peeking through with his head, raising his voice, smiling flirtatiously, as he insists he needs to get reading. Henry really wants him to go but maintains his politeness as he crosses the room toward the sideboard to get Sandra the requested whiskey and ginger.

Kenneth then rather brashly maneuvers himself, swiveling his hips like a professional dancer, into the seat next to Sandra, while Henry looks on and has to take the chair (this is different than the stage direction in my script).

Once they’re all seated, Sandra confesses that she’s stoned (to me, this wasn’t totally intelligible from Ryan’s performance and I think it should have been. I haven’t had a lot of experiences with people high on marijuana but from the few I have had, Sandra has seemed a bit too coherent up till now to really be high).

Audience laughter for Sandra’s confession, her insistence that it’s pot and not alcohol, her statement that she smokes too much of it, and Kenneth’s response that he doesn’t think that’s possible (silly interjection: I love how Armitage says the word “possible”), and oddly, for each of their lines that it’s “jolly” (not sure that’s funny, but by this time given all the herbal cigarettes maybe the audience is a bit giddy, too. Or are we laughing because that’s such a glaring Britishism and out of date to boot?).

About a fifth of Act One is left, and at this point Sandra raises the problem that motivates the end of the piece — they don’t have anything to eat, apparently due to a misunderstanding between them about who was cooking (at this point my goodwill to the character is still positive enough that it’s an open question to me whether she’s gaslighting him, but at the end of the Act I think she probably never was planning to cook dinner for him anyway). Laughs at the end of each line throughout this section, because Henry’s discomfort with Sandra is also strangely funny, so it’s hilarious when he says he doesn’t have any weed although he’s certainly not happy about it.

Kenneth admits to having weed. Henry is then angry because he didn’t know and it’s illegal. Sandra pooh poohs the legal problem and tells Kenneth to go and get it. While he’s gone, she insults Henry’s hair. Huge laughter.

S: I don’t like your hair.

H: It’s always like this.

S: I know.

[Mike Bartlett, Love, Love, Love (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p.47.]

The essay in the front of the 2015 edition, by James Grieve, cites these lines as an example of how Bartlett can pack a whole story into a few lines, including character insight. I disagree with that slightly — I don’t know that I see a character insight here so much as a kind of final confirmation that these two people are not meant for each other. Maybe that is a character insight. I establish that I really don’t like her precisely at this point, but still, it’s hard to stop laughing at her.

Kenneth returns with a little tin and sits back down on the sofa and now, for several moments, the audience has the pleasure of watching Richard Armitage roll a (fake — I assume) joint, completely with getting little wisps of marijuana on his tongue and lips and having to pick them off, sticking out his tongue to wet the rolling paper, and so on.

Armitage doesn’t do this ostentatiously, but I’m a fan and so I watched it closely and laughed internally. He looks at that joint with a small, happy smile, and contented eyes, a bit like I look at a cupcake with a lot of frosting on it. While Kenneth is rolling, Henry objects that Sandra hadn’t told him about her job, and she begins a vociferous objection to the assumption that she has any obligation at all to Henry. Here, she takes on a very pedantic tone that is somehow very sort of half-baked nineteen and funny, particularly when she establishes that Henry is twenty-three to her and Kenneth’s nineteen and says in a tone of officious concern, that that IS older. Now she takes up the refrain of how things are changing before she notices that Henry is taking on a greater and greater resemblance to a storm cloud. She makes her last real attempt to pacify him, abandoning Kenneth and going to sit on the arm of Henry’s chair, saying that Kenneth is a little boy, not a man like Henry.

Henry again says Kenneth needs to leave and at this point Kenneth gives up all pretense of cooperation with a facetious grin and stays put. Just like Kenneth, Sandra won’t have it — at this point she’s clearly decided that she’s putting her money on Kenneth, and she gives Henry a guilt trip that he’s too polite to resist. Henry hints that they should spend some time alone, but Sandra raises the bathroom access objection from earlier, and Armitage garners huge laughs for pulling his feet up on the sofa as if he’s being threatened again, and pouting, whining to her that Henry wanted him to use a bucket. Sandra negotiates Henry into having “a party.” Kenneth agrees, lights the joint, and then gives it to Sandra, who has crossed to stage left, near the table, and gets a longish speech from Bartlett about her encounter with a policeman.

This didn’t work especially well any time I saw it. There could be any number of reasons. The audience does laugh at the pun that frames the joke (Sandra calls the policeman “cunt-stable” several times, emphasizing it because the character thinks it’s funny) but “cunt” has a different valence for an American audience; for us (large generalization here, ymmv) it’s a strong obscenity used primarily by men, and for Brits it seems to be another way of saying “idiot” and everyone says it. So the joke seems more brutal to me, I think, than it might to someone from England. Secondly, what is supposed to sound silly (the notion that women think they could be raped at any time) and probably did sound silly and perhaps a bit pretentious in the 60s in England, has been a central topic of public discourse in the U.S. for the last year in light of numerous well publicized sexual assault cases at universities. In that sense, this speech is just ill-timed for this particular audience. I’m supposed to think she’s being silly and hyperfeminist and actually I think she’s right on target. So I don’t laugh. Further, I think the line about beds (“I’m not sure about beds”) should get more laughs than it does, especially given the atmosphere in that room. For someone who’s flirting with as much intention as she is, Sandra seems oddly unaware that she’s speaking in double entendres and it’s hard to believe that someone who speaks so pretentiously could be unaware of that. So finally, and I say this tentatively — I don’t think Ryan revealed a strong sense of what about this speech could have been funny (her officious tone, the line about beds). Here a goofier or hammier vibe would have suited her better than the preachy tone she takes on, not least because she is delivering this speech while smoking a spliff, supposedly after arriving already high at the apartment).

At the end of the speech, Sandra crosses back via center stage to give the joint back to Kenneth sit and stand between Kenneth and Henry. The topic turns to music as the characters debate the relative superiority of classical vs. popular music. They get some laughs for the lines about Cream, but again I think this should have been funnier; there was another double entendre there that could have been exploited more effectively. Where it does get funny again — and the point at which I believe, for the first and only time in Act One, that Sandra could be high — is when Sandra delivers her lines about why she loves dancing. Something’s so incongruous about the analytical vocabulary that she abuses essentially to say she likes to move around. And her dance while she’s doing it is hilarious as well. Big laughs from the audience.

It turns out that Kenneth (not Henry, as Sandra rubs in) has the records Sandra wants to listen to, and she sends him away to get them even as she tells Henry they need food. As he doesn’t want to dance, she suggests he go to the “fish and chip shop,” then, so that she and Kenneth can have a bit of a dance. Henry warns Kenneth he’ll be back in ten minutes before he leaves with an air of suppressed violence.

Now that they are alone, the action toward which Sandra has seemed to be aiming for the last third of the act and to which Kenneth has been contributing in order to annoy his brother seems imminent. The vibe in the room changes; Kenneth suddenly seems less flirtatious and Sandra, even more predatory. Kenneth is a bit nervous about Henry’s anger and oddly preoccupied with the records he’s brought out. Kenneth, whose been needling Henry all evening, suddenly defends him when Sandra calls him old-fashioned, noting, “He likes you.”

Sandra and Kenneth reunite on the topic of their love for the new and the fresh — Kenneth utters a line (“I get bored easily”) that will reappear, eerily, in Act Three, to mean something entirely different, but here the atmosphere is still peppy and upbeat. She and Kenneth begin to contrast themselves to Henry in their lines, and what’s been funny up till now takes on this idealistic light that becomes just a little tinged with anxiety.

They both preen with their bodies and Kenneth’s praise becomes simultaneously shy, direct, and unabashed. Kenneth takes on a stance like a courtier, and Armitage gets a few laughs for these cheeky lines and the awkward ways he finds to tell Sandra that she’s (physically, sexually) attractive. Ryan gets laughs for her mild desperation about her sister’s body and her desire to feel young forever.

Sandra swoops in for the kill, asking whether Kenneth and his brother have ever “shared” a woman. Kenneth seems taken aback and they get some laughs for this although the atmosphere in the theater is now quickly changing. The conversation is as rapid-fire as earlier, but now, additionally, breathless. She baldly states her desire (“I like you”) and Kenneth shows, for more or less the first all evening, a glimpse of a self that isn’t projecting bravado or provoking annoyance when he acknowledges her statement but states that Henry is her brother. She argues that Henry will get over it. Kenneth is still nervous, running his hands through his hair, as she notes. When Kenneth hesitates in the face of her proposal that they just dance a bit until Henry returns, Sandra ups the ante by telling him they’re going to die. (It’s significant to notice this as this motif reappears in both Acts Two and Three as well.)

As you know, Armitage’s citation of Sandra’s lines at this on November 10 led me to a huge internal uproar and to suspend blogging for four days. I think anyone who’s familiar with the point in the play will see why. On the one hand, yes, it’s an idealistic statement of a 60s hippie vision of a perfect world in which all anyone needs is freedom; on the other hand it’s the most pretentious come-on ever, because the concrete “structure” that Sandra wants overthrown at this point is Kenneth’s loyalty to his brother (who’s shown an irritable generosity all the way through this act), so that she can get what she wants, which isn’t really an awareness of how all people are alike, but rather Kenneth, and she’s quite aware that Kenneth would like to overthrow it as well. He still doesn’t cave, she proposes “adventures” (this made me think somewhat inappropriately of The Hobbit), and then asks him if he’s found some music to dance to.

The earlier mood of the child who thunders across the room as Kenneth looks at his watch, dashes to the television, and turns it on. We hear the blaring opening brass of “All You Need is Love,” in the tinny television audio, and Kenneth frowns a bit. But they find a rhythm,

and they begin to dance.

To me, the way they are dancing, the looks on their faces, are very reminiscent of what I think of the attitudes on the floor of British dance halls toward the end of the 1950s — but I admit I only have that picture in my mind due to film, having myself only been born in 1969, two years after the action of this act of the play. In any case, they look a little dazed, a little attracted, a little aroused, and they only have eyes for each other.

And then they kiss:

But not for long, as Henry bursts in:

And they all have to face each other:

Sandra moves toward Henry, to touch his face, but he turns and leaves the apartment. Kenneth is at the front of center stage, looking after Henry, clearly realizing, at least briefly, that he’s won the game he’s been playing all evening but that he’s done something much more momentous than simply get under his elder brother’s skin this time. He turns down the television and collapses back on to the sofa.

Sandra comes to him to reassure him and suggests to him that they could live in Oxford. Another bit of a laugh from the audience both at that proposal and the fact that Kenneth is floored by it as well. She gets some laughs when she informs him that Henry will be happier when he’s found a girl to whom he’s better suited, “a slightly duller, traditional kind of girl.” Kenneth is already rationalizing as she proposes they can do what they want, all summer.

She asks him if he’s ready? For what? For adventures. And as she falls into his arms (which she does with utter confidence, I was impressed by how much she must trust him to catch her at that moment, as she’s a dead weight), there’s a split second of bliss on his closed eyes and face and the lights snap off, the curtain falls, and the interval music is cued.

[Continues here.]

~ by Servetus on November 23, 2016.

Posted in Richard Armitage

Tags: acting, Alex Hurt, Amy Ryan, comedy, Henry, Kenneth, Love Love Love, me, Mike Bartlett, Richard Armitage, Sandra, theater

46 Responses to “Love, Love, Love: Attempt at description, Act 1 [spoilers] #richardarmitage”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

First of all – thank you for this. It brings back the play and many of the facets of the acting, interacting, staging etc. – I am amazed at how much you remember, and many of your observations now trigger things that I noticed and thought (and found good or bad), too. Most of all, I find some of my own impressions confirmed – such as the strong consistency of Armitage in his performances (of which I saw 4) as opposed the varying approaches of Ryan.

LikeLike

This is a “house of memory” post — I think most people could do this if they had the patience to learn the memory technique. It’s even easier in this case because the play took place in a house 🙂

I really could not decide about her, even after the last performance. She also doesn’t have that really “intense” presence vibe — it seems elusive, to try to understand her.

LikeLike

Sherlock’s mind palace – I should’ve known 😉

And I am with you on Ryan being elusive – slippery, difficult to gauge.

LikeLike

I hope it’s OK to comment about parts, because I’m still reading. We agree that Amy Ryan was not as successful at being 19 as was Richard Armitage. Perhaps as a female, there was no convincing way to change her movement from age to age in Acts I and II ( and there was no change in III either) the way there was a with a young Kenneth growing into a more mature man. You could contrast his flitting, comical physicality in Act II ( somethig that also showed the pattern of little brother/big brother) with something different in II or III, but Sandra pretty moved the same throughout. She strutted and “arrived”. I could easily get over the fact that her face could not look 19 – it was the text and her speech that I didn’t believe. Her dialogue was too sophisticated and knowing for a 19 year old and it didn’t ring true whenever she was talking about general things, rather than specific experiences. Also, I thought her manner of speech, even though posher than the brothers’, was a tad too mature and professional – lacked the breeziness or haltesness ( for lack of better words) that a younger girl would use.For ex: she was OK when talking of the getting fired experience, her night in the park, meeting Henry, but when she got on to the state of the world, freedoms, predicting Henry’s reaction if we discovered Kenneth and her, etc., those were the words of a person with more experience and broad knowledge than a 19 year old would have. So, I blame it mostly on the dialogue and some of her delivery – but not at all on the fact that her face didn’t look 19.

LikeLike

I agree — although I think that the fact that other stuff didn’t jive meant I noticed her appearance more.

LikeLike

This was terrific. It brought me back to the play. Act I was my favorite because everyone was still pretty innocent and not so broken.

I agree with you about Sandra — she is not convincing as a 19-year-old. While Kenneth doesn’t look like 19, his movement and his speech are believable as someone 45 pretending to be 19. I totally believed that Henry and Kenneth were siblings. Sandra seems too pretentious, too flighty, too self important. Teens tend to show a sweet and vulnerable side to them even when they are pontificating on how the world should be, as Kenneth does, but Sandra is like an unfeeling bulldozer. During this Act, I was sympathetic to Henry, liked Kenneth but thought he was immature, and found Sandra to be a horrible person. So perhaps my audience was one that never liked Sandra. I enjoyed Sandra very much in the subsequent acts even though I still disliked her, but less so here in Act I.

In your comments about Sandra being the focal point, I felt like the women in this play were making the argument for the story, and the men were there to advance the plot. However, the men were far more likable and nuanced than the women, whose roles seemed to be so focused on making the point that they didn’t get to be whole people. I wonder what you think about that?

Random: I had never heard the term “bird” before to refer to women, and at first it seemed like a horrible derogatory word until I realized it is no worse and perhaps slightly better than “chick” that was used in the US in my childhood. At least birds can be adults, while chicks can’t.

LikeLike

Totally agree re: teens — as infuriating as a college sophomore can be, I found it a wonderful age to teach just for the reasons you say. Their off the wall moments. The line about beds was a good opportunity for that kind of moment and it was missed.

re: women not nuanced — it was one of my fears going into this play, having only read it, that it was going to come off as a huge anti-feminist screed. It wasn’t as bad as I thought it could be — so yeah, I agree. And that’s a script Issue, which makes me wonder a lot about Bartlett and his attitudes toward women.

re: bird — interesting. My impression is that it’s patronizing but not hugely derogatory (sort of like “chick” — although I always assumed that was derived from ‘chica,” I now read that it was Black slang in the 1920s, so it must be about the avian aspect).

LikeLike

I don’t want to read too much into Mike Bartlett’s relationships with women although I must admit that we left the theater wondering out loud what his mother is like! To his credit, he gave the female characters critical roles in his play. He made them less sympathetic than the men, but they really got to deliver the best and most important lines. This is far better than many roles for women.

LikeLike

I agree w/not reading too much into it, although attitudes are different from relationships. I think that one’s attitude toward a group certainly influences what one writes about them.

Amy Ryan liked the role for the reason you specify but that’s not necessarily a reason for me to admire or like the play as a whole. I was relieved, though, that it didn’t turn into wholesale feminism / woman-bashing. (Although I think that some critics, those who were already inclined to agree with that point, did see it in that light.)

LikeLike

I see your distinction between his own relationships and his attitudes.

Another possibility is that it is more about what he understands rather than his attitudes about women. I recall reading that Jane Austen never could write about what the male characters were thinking but only showed them in mixed company because anything more was out of her experience.

I sense Bartlett thought he was critical of everyone equally in this play given that Kenneth and Jamie behave badly throughout too, but that is not how I experienced it. Since Henry seems like a decent guy, that also skews things a little more negatively for the women.

One of the things I’m always on the lookout for (as someone working in a male-dominated field) is whether men and women are given the same opportunities. In this play, I think it is a little mixed in that the women have the more important roles but their characters are awful. But by and large I think Amy Ryan’s role (and to a lesser extent Zoe Kazan’s) are better than most. You are right that this is not a reason to base whether or not you like a play, but it offers a little bit of insight into the writer, and it pleases the part of me that wants women to have equal opportunities.

LikeLike

re: Austen, yes, although you’d think that someone living in the 20th/21st centuries might have a broader experience of the opposite sex. But on the whole, based on the plays that I have read (Wild, and Charles III), I don’t believe that believable characterization is his strength anyway, or maybe it’s not even a goal. He seems more interested in “saying something.” This is in line with the genre — it’s a social snapshot.

I guess I’ve always been ambivalent on the “equal opportunities” question as a principled issue. For me, it’s sort of like — yeah, in theory women should equal in the military but I’d rather not have a military so I’m not going to get too exercised about it. I agree female characters in any hypothetical play should have an equal opportunity to be jerks, though.

I’ll get on to Zoe Kazan in the next post more, I suppose.

LikeLike

Thank you very much, Servetus. This is the sort of thing you excel at. And, since I shall not be seeing the play unless it’s filmed, this must be the next best thing. I remember seeing that TV transmission and wearing a dress like Sandra’s and being ‘in transition’ with my pronunciation of ‘will’/’wiw’ (great observation.) When I read the play, btw, and saw that reference to Joe Orton, it made me laugh. Is Sandra suggesting that Henry looks gay in his leather jacket? I thought it was pay-back time for Henry saying that Kenneth looked gay in his dressing-gown. Looking forward to your description of the next two acts.

LikeLike

Interesting notion about Orton — could well be. (As I said, it more or less flew past the entire audience in NYC.) That would make that moment even funnier.

I’ve got to edit this — uch. And then I will get on Act II, but tomorrow is Thanksgiving and then we have five deer to butcher on Friday which will take the lion’s share of the day … or maybe they’ll let me not help, lol.

LikeLike

The first night I saw the play, I thought it had more low energy in Act I than subsequent performances. Mostly, because I found Richard Armitage to be a little less flamboyant in his movements. One example was less drama and mugging when he posed himself to wait on the sifa and flung his robe open before Sandra’s entrance. Of course, I had nothing to compare it to at that point ( and I think I was also overwhelmed by seeing him live, how close he was to me and how utterly different he was in this role than any other, including interviews where he’s just himself). I was having trouble processing my that Richard Armitage as Kenneth. Overall, all nights, I thought he was a huge success in Act I. Whether it was 19 or some other young age, he definitely got across that he was on the immature side. He must have been a success , because his character annoyed the hell out of me for how he acted as a pain in the ass younger brother- and I don’t even have a younger brother. He was successfully bratty.

The size difference between the brothers didn’t bother me because has you pointed out, Kenneth was wispy and bendable – fast moving, compared to a more solid, planted Henry. Also, these patterns of how family members act, IMO, stay the same from childhood, so if Kenneth was sometimes cowed by Henry, that wouldn’t change, and if Kenneth was always wheedling, underfoot and undermining, that wouldn’t necessarily change either.

I noticed immediately that he used the word television instead of telly and chalked that up to the decision to slightly Americanize the dialogue. I think “birds” for women, is pretty well known in the US – for some reason I keep thinking of old Michael Caine movies. I agree that “Cunstable” was probably funny to part of the audience, but at least half the women when I was there hated it. Might have tolerated it once, but I think she said it twice at least. If I would have been able to suggest one dialogue change, it would have been to exchange bog paper for toilet paper. By then, I knew what it was, but I don’t think I would have gotten it – and the comedic dialogue and timing around its absence was hilarious.

LikeLike

I think you’re right on the general point that the first time I’ve seen anything of his live, I spend half the time thinking “it’s Armitage” and reminding mysel to breathe — and I agree emphatically on the sort of shock of how different this role is from everything else. I had been kind of neutral on the whole “does this need to be recorded” theme (sort of thinking, yes, for the fans, but really only in their interest). And maybe he did stuff like this all the time before 2002 and it’s just that there was no one documenting it — but this is a total departure. I used to watch Dibley and think, you’re right, you’re not all that good at comedy, but this? (I’m still contemplating my theory that it’s the kind of humor that matters and that he might just be better at irony / bitter absurdity, that it might square better with his personality or worldview or something.)

“Immature” is well put. He successful conveys the immaturity of a 19 year old whether he looks that way or not. Maybe he put his own younger brother moves into this — but OMG. Verisimilitude.

Def agree re: patterns of interactions persisting from childhood.

re: television — “television” is in the first UK script (as is another one that mystified me a little, “fish and chip shop”). I would have expected “telly” and “chippie,” although a smart person would never say the word “chippie” in front of a US audience. Maybe those terms weren’t in common use back then in the UK? In any case Armitage himself seems to say “telly,” at least I can think of two instances of it.

thanks for your read on “cunt-stable,” I didn’t have anyone else to ask.

re: bog paper. I suspect you’re right. No doubt also because beans eventually require the employment of bog paper …

LikeLike

What was un-British about “fish and chips shop”? It sounded British to me. “Television” in the script was something I didn’t remember and I can’t recall whether I was surprised or not. How do Brits use the word “television”? Do they use it at all? Probably in ads for sale. I thought that was a great bit missed by many non-Brits except for fans.

Re-Cunstable – I gather the C word is more acceptable in the UK even now. I re-read my comment. I was trying to say that my impression, as well as my experience was that half the audience or women were made uncomfortable because of the pun – but the word is showing up more and more all over the place. Women are having conversations about the use of the word and in different contexts. I predict that in a generation or less, it’s going to lose its punch. I worry that’ll also be the case with other heretofore unsayable epithets.

LikeLike

My British friends call it a “chippy.” But that may be slang that postdates this play.

re: degradation of speech — I hear you. I’ve been thinking a lot about Victor Klemperer the last week or so. In addition to his diary, after the war he wrote a really important book about the degradation of speech under the Nazis.

LikeLike

[…] Servetus has posted almost a blow by blow of Act I with editorial comments. Check in there for the early part of the discussion in comments. Great for anyone who won;t be seeing it, and fun for everyone who has seen it. Also, check out my comments there for some of my reactions. I haven’t given up on posting about my own experiences on my own blog – really. […]

LikeLike

I wondered how much of Kenneth’/ mannerisms came from the real life relationship with his own older brother. He’s had some experience of being the baby in the family.

The character of Kenneth reminded me so much of one of my favorite HS library aides – Issac – who had the charming slacker role down to a tee. He was much better at making out with his girlfriend behind the stacks than he was at keeping his shelves in order.

I know I was supposed to be impressed by Amy Rayan’s performance, but it irritated me. I think there was a sameness in her vocal quality and line delivery that just grated on me. Yes, Sandra was written that way, but it was deeper than that. To me, Sandra lacked the nuance and shading that the other characters had. I’d be rolling a joint, too, if I had to spend time with her, and I don’t think I’d share. (of course, I suspect I’m in the minority).

Regarding “stoned” Sandra. I was born in 1961. Pot during that era wasn’t nearly as potent as it is has become. In high school, when I tried it, we had to smoke half the bad in order to feel anything at all. So I did accept her “stoned” performance.

LikeLike

And the baby who’s “special,” if I remember correctly, Armitage’s brother works in something to do with cars.

I agree that Sandra was unlikeable / hard to take. Particularly in terms of her relationship with her daughter. That line about how Rose is attractive when she takes the time just hurt. Hurt.

Good to know about the previous iteration of weed. I never tried it. Just ran into people who had.

LikeLike

I think his brother works for the DMV, making him the “responsible” one who went into the civil service.

Sandra irritated the heck out of me. Just the tone of her voice grated on me. I won’t even get into her personality.

LikeLike

I want to do a separate post on Amy Ryan …

LikeLike

but I think the character is supposed to irritate you.

LikeLike

It worked. It’s a month latter and I’m still irritated. An irritating character to put the cherry on top of a month of irritations.

LikeLike

WOW !Thank you,Servetus 🙂 I can’t wait for part two !

LikeLike

You’re welcome. Sitting down to work on it now …

LikeLike

I can’t see the play, so this is the next best thing. Thanks for this detailed description!!

LikeLike

Glad it’s useful — basically, you are the target audience.

LikeLike

🙂 🙂

LikeLike

Finally got around to reading this – I wanted to do so in one sitting. Thank you for such a detailed account, especially about RA’s Kenneth. I’m looking forward to reading about the second act. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for reading — I realize it’s non-trivial!

LikeLike

[…] from here. Please be aware of list of caveats at the beginning of that post. This is the first half of Act […]

LikeLike

Love, Love, Love: Attempt at description, Act 2a [spoilers] #richardarmitage | Me + Richard Armitage said this on November 27, 2016 at 8:16 pm |

YES! Thank you! I think I can almost picture him in this role; your awesome description (still chuckling a few days later) along with the released videos . and his Cbeebies narrations (for some weird reason) give me quite an idea XD. Plus one or two Gisborne moments. Vicar of Dibley not so much though, has another vibe to it…

LikeLike

I hadn’t thought of that comparison (CBeebies) but it’s a really good one, actually. There are moments of irony in there contrasted with the silliness and that’s a good parallel to this (which isn’t like Dibley in the least, and isn’t like Armitage’s own sense of humor in interviews, either).

LikeLike

Yay the comparison works :); thanks for clarifying my impression. Silly Armitage is a close favourite, so Cbeebies really stuck cough.

LikeLike

LOL.

Also, the exaggerated hand and arm movements.

LikeLike

I’m late to the party, so only just now diving in, but I love your thoughtful analysis here. I haven’t seen the play, but it’s nice to learn that Armitage is doing some comedic performance again. It seems that lately many of his roles have been, well…dour. (Or maybe it’s just that some of them aren’t to my personal taste.) It just seems like we haven’t seen so much as a drop of comedy since the Dibley days…good to see him rounding out his repertoire again.

LikeLike

I’m glad you enjoyed it. (You may tire out … I did, lol.) He is IMPROBABLY funny. I suspect he’s someone who is often underestimated.

LikeLike

Oh, where to start!?! This recount is amazing, though I have to wonder now if I lucked onto a performance (my mezzanine/first viewing) where Amy Ryan just killed it, or I just had a different impression than you (and other commenters here)… I thought she commanded the stage every time she appeared, and loved every minute of it. I had no qualms and in fact a highly favorable opinion (of her performances – not her character’s virtues) but I will concede that in the following 3 performances I really only had eyes on Sandra whenever Kenneth was offstage, so it’s possible my impression of her was based on the first time I saw her, and if she was inconsistent I didn’t pick up on it because my eyes were always elsewherel!

One moment that I wish to point out that I found highly funny was when Sandra was suggesting the three of them party together and there was a double entendre about a “threesome”… Kenneth’s eyes about popped out of his face and the “OMG my fantasies have just been realized” way he kind of gulped and his voice broke as he says, “Yeah!”… so funny! (And so 19 year old male!)

Really interesting some of your observations. I have known people who could really pontificate while smoking pot, and sound pretty “deep” while doing so, but sometimes it will abruptly veer into something that sounds profound only to the the smokers, ie “I’m not sure about beds. I’m really not.” I loved Henry’s face right after she delivered this line and asked him if he wanted a drag off the joint… a real “Not only no, but HELL no” expression!

LikeLike

I was just going over my notes from individual performances — she was just not good the first night and then the second night I saw it she was probably at her best. Drastically different performances.

re: the threesome thing — I don’t think any audience I saw that with really got that joke. But the first act was just okay the first night I saw it.

LikeLike

Yes, that one had a variable response- good laughter a couple of times and only a few snickers a couple of times. It is interesting how any given performance (and audience, as well) can sway your perceptions. The night I was in the mezz, the audience was really engaged and really laughing, more so, maybe, than at any other performance. The subscriber-heavy audiences weren’t so collectively engaged.

LikeLike

I think (besides any other factors that might be in play, such as their age or their wealth or whatever) a theater subscriber sees much more theater than the average person and certainly than the average Armitage fan — I know that my reactions were influenced not only by the fact that “it’s the Armitage!” but also because I’ve only been to the theater twice this year, and both times were community theater. “New York Theater” is really world-class standard and that difference has an effect on me as I’m not accustomed to it.

LikeLike

[…] now that I’ve documented what I saw in general terms (Act One, Act Two [part one, part two], Act Three), I can drop my more personal impressions from the trip […]

LikeLike

Performance impressions, Love, Love, Love 11/3-11/6 #richardarmitage | Me + Richard Armitage said this on December 11, 2016 at 8:06 am |

[…] detailed insights into the play act by act from Serv here (act 3 ) , here (act 2 ) and here (act 1 ) (which I can now finally read!) And you’ll also find in these further links to her […]

LikeLike

[…] started writing the documentation of that visit (out of the rationale that I needed to do at least that) and I got to the place that I remembered […]

LikeLike

Those are pearls that were his eyes: me + Richard Armitage sea-change? | Me + Richard Armitage said this on March 21, 2017 at 7:40 am |

[…] Armitage has two connections to Joe Orton: they were both from Leicester, and in Love, Love, Love, Sandra references Orton briefly (that was how I learned who he was). If you were not able to tune in at that time, the reading has […]

LikeLike

ICYMI: Joe Orton in social isolation + Annabel Capper | Me + Richard Armitage said this on July 10, 2020 at 7:42 pm |