Love, Love, Love: Attempt at description, Act 2a [spoilers] #richardarmitage

Continued from here. Please be aware of list of caveats at the beginning of that post. This is the first half of Act Two. Add to that:

- At this point it gets harder to describe what exactly the audience found funny, because the reactions differed on different nights. I’ll try to give notice of that when I remember it, though. I hope it’s not too confusing.

- This act has a definite “arc” of energy (a more overt one than Act One or Act Three) and whether it is convincing, or how it is received by the audience, depends a great deal on the rhythm and the audience reaction of the first half of it. Essentially I think the play tries to build up a lot of good will in terms of seeing the characters as harmless or at least stereotypically funny — if we accept that for the first half of the act, the second half works better.

- I’m probably using American nouns in this section that might not necessarily be used by people in the UK (e.g., I consistently write “living room” but it’s not typically called that in Great Britain as far as I know).

- If there was a lot of “over each other” dialogue in the first act, there’s even more, here, and this contributed to the question of whether the audience was hearing stuff as a joke or not. It was extremely variable, I found, whether I was hearing key lines of the script on any given evening. This technique as Bartlett uses it has generally been praised (both by Armitage and David Hewson, at length), but at times (or if it’s not really orchestrated perfectly by the actors) it really interferes with audience comprehension of what’s being said.

- I suspect that the drinking / smoking aspect of Acts Two and Three would be perceived in subtly different ways by a British vs. an American audience. My hypothesis is that (in general) Brits would be more likely to view much of the drinking or offers of drinking in Act Two at least (with the exception of Sandra) as humorous whereas Americans would be troubled by it and the jokes about it. (I note this not because Americans necessarily drink less, but because the drinking cultures seem strikingly different to me. Americans are also generally more self-righteous about smoking than any other culture on the planet, I find.) I think the way the parents press wine on their children is meant to be funny, but I also think it’s not inconceivable that a sixteen-year-old would be offered a glass of wine on her birthday at home in England.

***

ACT ONE INTERVAL

As the curtain falls, the interval playlist is cued up. If Act One has gone well, the mood in the theater is very positive afterwards, with lots of conversation, people standing in the aisles to chat, humming along with the music, and so on. (It was that way on all except one night I saw it, when I felt like timing problems between the cast members negatively affected the level of laughter.) Ushers go to the front of the theater and stand in front of the curtains (not sure why, but it was pretty ostentatious. Maybe somebody tried to peek behind them or something). You will see people with beverages in their hands and the atmosphere is generally really good. After ten minutes, the house lights and music begin to fall. When everyone’s taken their seats, the curtain rises.

ACT TWO

Act Two is set in a single living / dining room in (as we learn later) in Reading, Berkshire (pronounced “Redding”), a city roughly equidistant from Oxford and London. Armitage indicated his interpretation of Reading’s “meaning” as a reference here at 16:42, a “perfectly manicured” place that was “nice” but “just nice,” and from which nothing earth-shattering was likely to come (I found that a very revealing comment). Here’s how google thinks the exterior of a terraced house (per the script) in Reading should look. The set is intended to reflect English lower middle class living in the 1990s (referencing our discussions elsewhere that class in the UK is not as directly related to income as it is in the U.S., so that, to a U.S. audience, this room definitely looks comfortably middle class and perhaps — because of the art on the stage left rear wall — even a little better, although an American family would probably not have had an informal dining setting in their main living space in 1990). The room is lit with comfortable and generous, warm lighting (not the rather stingy lighting of the previous act, nor again like the brighter lights of the final one). At far stage left is a television on a cabinet; immediately to its left and behind it is a dark brown wall unit bookcase, filled mostly with books. I recognized two books that I read in university (1987-91): a biography of Margaret Thatcher, and Thomas Friedman’s Beirut to Jerusalem (1989), about the first Intifadah, which won the Pulitzer Prize. So: It looks like some people in the family care about staying up to date with contemporary politics. The bookcase also has a contemporary black plastic stereo receiver and cassette deck, and some photos (one is definitely of a wedding couple or party — perhaps Sandra was married in a floor-length white dress. Would not necessarily have expected that).

Between the television and center stage we see an uncoordinated living room furniture group, settled on an area rug with an abstract design of swirls. Toward center stage is a Wassily chair and between that chair and the television is a postwar Danish-influenced sofa (looks like something you’d purchase from Knoll). This furniture, along with the thick Picasso coffee-table book on the coffee table, the abstract painting on the wall at rear stage left, and the abstract pieces in the hallway behind the stage, suggest an affection for modern design or an attempt to demonstrate a particular kind of taste, although not necessarily a high level of consumption, as all these designs were available as knockoffs in the UK, which didn’t tighten its copyright protections on furniture design until very recently. To me the coffee table doesn’t fit stylistically with the rest of the room, but they did need something Jamie could stand and dance on. Also at stage left we see a dining table with four Danish-moderny chairs, in front of a cabinet that holds a phonograph and where Kenneth leaves some of his records.

Behind the living room we see a hallway area with a two-section abstract art composition on its wall and paths leading off stage left and stage right. Off stage-right rear appears to be the exterior entrance to the dwelling and the kitchen or pantry; off stage-left rear is a staircase that appears to lead to a bedroom area, upstairs.

When the lights come up, Jamie (Ben Rosenfield) walks in from the hallway stage right wearing his school uniform.

[Editorial comment: Rosenfield has potentially been under-acknowledged in the press for his work on this play. It’s a minor role and probably easy to overlook given the chaotic energy of the piece in general. There’s some suggestion in the script at the beginning of this act that he’s a bit “off,” e.g., a fourteen-year-old who can’t be left alone for a few hours, and it could be hard to play that unobtrusively at this stage in the game. Rosenfield hits effectively the vibe of a weird fourteen-year-old, with his kind, disgusting, and mean moments emphasized equally, and he has a really interesting way of screwing up his mouth and his face when he’s suffering that rings true. His teenage voice is similarly just a bit nasal, as if he’s still coming to terms with it. And he has that point-blank dead-pan deliver of the kid saying the wrong thing at the wrong time that reminds me of every little brother on the planet.]

He’s barefoot and his fingernails are painted black. He turns on the cassette deck, and begins jamming to the song, pausing to take a look at the television screen and grab a candlestick to use as a microphone before he jumps up onto the coffee table. At first he is only lip-synching, but by the fourth line at the latest he is singing along loudly and in tune. He kicks the book (a heavy study of Picasso) off the table toward center stage as he dances.

Eventually, Jamie appears to hear that someone’s arrived, as he jumps off the table, puts the book back on it, and the pillow (which was already on the floor — these are different than the stage directions in the 2015 edition, which might have been more comical than this was, although this was really funny and Rosenfield gets plenty of amusement from the audience, especially when he sings “kiss me where the sun don’t shine”). We hear Kenneth yell, “Jamie!” The music still plays as he’s finishing straightening the room, and Kenneth enters from rear stage right, walking with a brisk business-like walk into the hallway and then into the room, coming to stand at rear center stage, initially behind the Wassily chair.

This is how he’s dressed and where his feet are is about where he’s standing (this is taken from a slightly later moment in the scene, just to give you an idea).

Two things to note here: first, Armitage’s physicality in relationship to his physical comedy, and then, his speech.

In this act, Kenneth is closest to Armitage’s own age. Armitage abandons the physical features of Kenneth in Act One completely (to the extent that I noted to myself that I needed to look for some physical connection between the two ages because the connection is not completely obvious to the viewer). Nothing appears unnatural or feigned about Kenneth’s movement in Act One (yes, it’s exaggerated, but it doesn’t seem false, really), but Kenneth in Act Two is purposeful in his movements; he’s gained some polish and charm — he is not just lazily insouciant or provocative, but he’s mature. He’s learned how to stand; while he still seems to have extra limb length he has it under control. He’s lost his sense of wonder at the changes in the world developed some fixed attitudes. And I think the link to Act One Kenneth lies in an aspect of this control: when Kenneth is being his most provocative in Act One, it’s because of that “whack-a-mole” quality; it’s hard to catch him. When Kenneth is being physically funny in Act Two, it’s because the character has learned to pose. Both of them share a common desire for attention, but the more mature Kenneth has learned not just how to spark it, but how to attract and hold it.

In Act Two, Kenneth’s voice moves lower, into Richard Armitage’s normal range. Probably Kenneth’s speech in this act is closest to Armitage’s own normal speech, but it’s not exactly the same, either, as I found myself thinking while re-listening to the Leonard Lopate interview on WNYC. Kenneth has transitioned away from the remaining landmarks of working class speech that were audible in Act One (swallowing the flap [li’el for little], fuzzy closing “l” in syllables). I might describe Kenneth’s speech here as rounded or perhaps “with the edges worn off,” i.e., he is now working in an office setting with a common standard of speech and his speech conforms fully in a sort of nondescript way. He sounds like a teacher or a civil servant (although his career is not specified), and in general the features of Kenneth’s speech are much less marked or distinctive (even than, say, Lucas North’s). I suppose you could say his speech is a bit like Armitage characterizes Reading: “nice.” In comparison, Armitage’s own unreflected normal speech still shows edges and corners, particularly much more percussive closing consonants, relatively aggressive performance of the alveolar flap, occasional missing consonants, and slightly different vowels (in particular long “i” which sounds more like “oy” to me in the radio interview than it does on stage).

The scripts I have have Sandra responding to Kenneth’s statement that the house is still in one piece from off, but I didn’t hear this if it happened in New York. The audience is primed that it’s supposed to be laughing at this point, and this statements gets a few. The Stone Roses are still playing pretty loudly. Kenneth also still has a coat on at this point, as I remember. He asks Jamie what the music is, and when he gets his answer, he starts bopping his head and shoulders in synch with it, while holding his lower body stationary, which gets quite a few laughs, as does the following line (“they can’t sing”). They start a quick back-and-forth about how Kenneth can’t sing either and the audience finds this funny although Jamie seems to find it somewhat less so. Kenneth tells Jamie to switch it off and exits rear stage right again. Jamie takes the cassette out of the player and sits down on the end of the sofa nearest the stereo. Kenneth starts from off, yelling about how Rose might have been “playing to no one.” Rose interjects (we still can’t quite see her) that it’s all right (awl right). Kenneth continues with this theme as he walks back into the room from rear stage right, now without coat, with grey jacket, trousers, blue shirt, tie. (That outfit is the epitome of my high school choir teacher ca. 1986. Especially the trousers, tie and shoes. I had a crush on him, too. Good look on a man.)

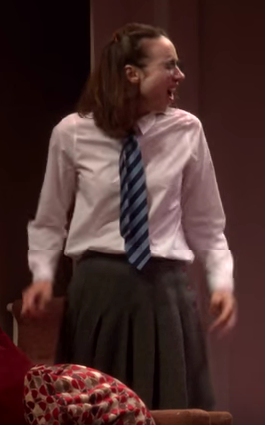

Enter Rose (Zoe Kazan) from rear stage right, crossing forward toward the front of the kitchen table. This is her general dress, although she has the girls’ version of the dark jacket Jamie was wearing earlier. They have the same tie as well, so I assume they go to the same school:

Zoe Kazan as Rose, to give you an idea of how she’s dressed, although this is taken from a later point in the scene. All UK schoolgirl at the end of the day.

In addition to this, she’s wearing a leather schoolbag of the type that my German friends would call a Schulranzen or maybe a Tornister, which looks like this:

and was worn like this, although the one used in the play might have had two shoulder straps:

and was worn like this, although the one used in the play might have had two shoulder straps:

She’s also carrying a hard surface black violin case that looks like this one in her hand:

Rose puts the violin case on the table, then crosses front and dumps her schoolbag and her jacket on the carpet and toes off her shoes.

Rose puts the violin case on the table, then crosses front and dumps her schoolbag and her jacket on the carpet and toes off her shoes.

[Editorial comment: About Zoe Kazan in Act Two, I find it very hard to judge, maybe because the “feel” of this act was so hard to gauge over the different times I saw the play, and I assume that a lot of how this character is played occurred at the behest of Mike Bartlett and Michael Mayer. One thing that’s undeniable is that the character is intentionally portrayed “over the top” in a way that Kenneth, Jamie and even Sandra (until the end) are not in this act. The question is how we respond to that excess-prone depiction. Sometimes she’s so outraged that it’s impossible not to giggle at her and Kazan seems like an undiscovered comic talent, especially with the exaggerated way she holds her body and makes her gestures. For instance, she uses her head position, her way of peering through her glasses, and her adjustment of the frames, all to great effect. Other times, she seems primarily to draw pity or sympathy from the audience (what she gets depends a lot on the mood the audience is in that night — I’ll give an example of the differences shortly).

Rose was the character I was most inclined to identify with before seeing the play, and I was surprised at how much more I identified with her after Act Two.

So I think she’s good in the role, and yet. First, Rose is supposed to be 16 (indeed, this scene has her ‘birthday cake’ at the end of it), but I found the character’s general stance and behavior throughout significantly less mature than that — more like 14. She very much still has that “don’t look at me, don’t talk to me, I’m so awkward I’d like to die” vibe of the fourteen-year-old girl, who hunches alternately because she feels put upon or embarrassed, or even because she hasn’t quite figured out where to position her chest yet. Most sixteen-year-olds, in my experience, have a bit more poise than Kazan’s Rose does — especially European teenagers, who have always seemed a year or two ahead of their American counterparts to me. The other thing (and this may also be Mayer’s decision) was Rose’s voice. Perhaps Mayer wanted Kazan to emphasize her voice’s nasal and whiny qualities for purposes of the role, but it sounds like she is performing entirely from her throat, with almost no diaphragm support, in Act Two anyway. She sounds vaguely scratchy in Act Three (as a result?) and I was actually a bit surprise today when listening to the WNYC radio interview today that her actual voice sounds so mellifluous.]

While Rose is dumping her stuff, four conversations are going on over about nine lines:

- Kenneth with absent Sandra over her failure to appear at Rose’s concert;

- Rose with Kenneth insisting that it doesn’t matter

- Kenneth with Jamie to turn the television off

- Jamie with Kenneth asking about what he’s seeing on the tv (poll tax riots of March 31, 1990).

This conversational style is true to life but confusing to observe on stage. Also, it’s another one of these “British moments” that definitely meant something to the original audience but definitely goes under here because the New York audience has largely no idea what they’re talking about. Not only that, they can’t even hear what Jamie and Kenneth are talking about. I think the point that it would have demonstrated is that Kenneth and Sandra are potentially deaf to the major political issues of their day; or, it might have suggested that they were supporters of the poll tax system (although that seems unlikely as they do not seem to be especially wealthy and there are four people living in that house); or that they have separated themselves from the protest mood of the late 1960s. In any case, it falls by the wayside here.

Rose sits down stage left of Jamie on the sofa. Ken only now notices that Sandra is not in the room and not listening to him. Kenneth sits down in the Wassily chair, kitty corner to his children.

Kenneth is a father who displays a sort of bluff, general bonhomie when speaking to his daughter, which he demonstrates not only with the content of his speech but with hand moments (sort of waving flat hands, for instance) and tone of voice. This family seems quite comfortable with each other in the sense that they are quite unrestrained in what they say and have no fear of disagreeing. On the other hand, the conversation — in which Kenneth compares Rose at her concert to cellist Jacqueline du Pré and praises her playing — reveals fairly clearly that Rose is aware that her father only sees his own version of her and is more or less impermeable to her attempts to interject or present anything that might present a different picture. But at the end of the dialogue, it emerges that Ken is primarily describing his (non-)perception of Rose’s performance so that he can bolster his picture of himself as a parent, especially in contrast to his wife, who may have missed the concert. Although the audience doesn’t notice it immediately, because we’re sympathetic to the general point, Kenneth is using Rose as a bat to beat his wife with.

And: practically every line gets a laugh. At this point it has something to do with the sitcom way this portion of the script is written, I think — the theme being “we all ignore each other.” It’s funny that Kenneth’s ego is so big; it’s funny when Jamie deflates it by pointing out that Jacqueline du Pré plays cello and not violin; it’s funny when Rose points out that she wasn’t playing a solo; it’s funny when Kenneth ignores all that. Jamie is a particularly good pesky little brother here, interjecting lines to gain attention.

I don’t want to give a line-by-line summary of the play; next the conversation turns to what’s planned to happen that evening. Jamie wants to go upstairs, Kenneth says he can’t because they are having cake. With that, he’s betrayed the surprise — another funny family sitcom moment and Armitage plays it for all it’s worth:

At this point Jamie sees his opportunity to stick in his knife (little brother behavior — wonder who he learned it from? — or real emotional insensitivity presaging Act Three? Rosenfield plays it right on the edge) and asks Kenneth why they are having cake, realizing that he’ll be able to catch Kenneth out for not being able to say how old Rose is. (This is a common problem fathers have, in my experience; my father was also never aware of my birthday unless driving or drinking was involved.) And sure enough, we laugh as Kevin squirms through this familiar situation. He can’t say, and Rose, for the second time this evening, insists defensively that it doesn’t matter. This is getting serious, but the family keeps going and the audience keeps laughing as, every time Kenneth asks her a question, she protests in some way or another, and Jamie continues to pester because he sees it has effect. It’s a familiar stereotype, the angry teenager daughter, we’re happy to laugh at her.

Kenneth can still be understood to be looking for common ground with his daughter, though; next he asks about her music teacher, whom she identifies as Mr. Parsons. But we also quickly see that it’s another identity move on his part, as the point seems to be that he and Parsons were at Oxford at the same time, but that “organ scholars were strange” (gender implication here?) Kenneth sort of shakes his hand to indicate sketchiness; audience laughs. All through this section we see the “mature” version of the young Kenneth with Armitage’s head moves, which are now slower, but still intend to indicate that provocative quality.

Rose, as it turns out, does not care for Parsons, “who smarms up to the parents, but in the classroom, he’s a total Hitler” (p. 64), a judgment that she reports earnestly and with the absolute conviction of an adolescent leaning forward. Laughter.

Jamie returns to action as the spoiler, insisting that Parsons is all right and he likes him. Zoe turns back toward him and says “do you?” and Jamie says, “It’s probably cos you’re stupid, he only likes smart people” (p. 65) and Zoe gets a great comic moment when she looks back at him, says, “I really hate you,” then cranes her head forward and pushes on the frame of her glasses. Huge laughter. Kenneth more or less ignores this, but then tells Rose that if she ever has trouble, he’ll intervene. She asks if he’ll beat her teacher up. Laughter. Kenneth says, no, he’ll call him up.

Kenneth: “No, I’ll get him on the phone and have a word. The power of rhetoric, much forgotten” (p. 65).

Rose thinks that fathers are supposed to look after their daughters (laughter) but Kenneth says “you’re looked after you get everything you want” (p. 65) — laughter — just as Jamie chimes in about being good at beating up people. Rose notes that her father never listens. I didn’t consistently hear this line every night but when I did, it got laughter. Kenneth exits stage right rear to check on the progress of the cake.

Then a moment ensues that demonstrates what I was talking about with different reactions on different evenings. Jamie and Rose are seated next to each other on the sofa and Rose is turned back, direction stage right, toward Jamie.

J: I hit someone last week.

R: Shut up. [laughter]

J: After maths club we were giving each other dead arms. [I could barely hear what he said here, most nights because of the over each other style]

R: “maths club” [laughter]

J: Paul nearly cried when I got him.

R: Can’t believe you go to maths club. [laughter]

J: What?

R: Such a geek. [laughter]

J: I’ll hit you. [laughter]

R: You’re too old to hit girls. [laughter]

J: It’s different with sisters. [laughter]

R: No, it isn’t. I’m a woman now. [laughter]I can say what I want and you can’t do anything. [laughter]

[Jamie rises from sofa, moves stage right to get behind it, and stands at its corner as Rose adjusts to see him.]

J: Daniel’s brother said that last Saturday at some party he burst into a bedroom and found Sarah Franks doing something to Mark Edwards that involved his penis. [He really screws up his face in a cruel smile while saying this, and sounds delighted to deliver the message. Big laughter]

R:

J: Isn’t Mark Edwards supposed to be your boyfriend? [here the mood begins to change — sometimes laughter, sometimes gasping]

R:

J: Thought so. You see? Don’t need to hit you. Happy birthday. Cake makes you fat. [sometimes uproarious laughter, sometimes a huge gasp or general outcry of “oh!”]

[Jamie exits stage left rear, going up the staircase.]

[Mike Bartlett, Love, Love, Love (London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2015), pp. 65-66. Italics mine.

I can’t venture to figure out all of the factors that make the audience laugh at, vs sympathizing with (via the gasp) Rose at this point, but it’s a really different mood in any case. I will say that when the laughing occurs at this point, the rest of the play goes better — it is supposed to be a comedy and if the audience is bothered by the dialogue so quickly into this act, it has a very hard time with the end of the act. On the other hand, it’s disturbing to watch these kids saying such horrible things to each other and be surrounded by a theater that is laughing to beat the band.

Rose sits sort of helplessly on the sofa as Kenneth returns from stage right rear and crosses to the table, where the violin case is sitting. He picks it up.

Expressing his regret that he didn’t learn an instrument (“we didn’t have all the facilities you have these days”) Ken then removes the violin from the table and uses it for a brief moment to play air guitar:

Kenneth: “and anyway, we all wanted to play guitar or drums, you’ve seen the photo. Classical took a back seat. You’ve seen the photo?” Rose: “yeah” (p. 66).

Armitage’s gestures — the air guitar, a wink, his crossing to the hallway and yelling up the stairs at Jamie to come down or he’ll send his mother up [laughter] — are expansive and they become more so if the audience is responding a lot. [laughter]. They all hide the fact that Kenneth seems to be seeking approval from his daughter.

This impression is reinforced in the next section, which on one level is a hilarious exchange about the fact that Kenneth argues that Procul Harum and Mozart are the same (he should have picked Bach for the comparison, he’d have had a better argument) and that Rose has no idea what he’s talking about — and on another represents Kenneth’s insistence that his daughter needs to understand him, cloaked in a familiar generational argument about whose music is worth listening to. Kenneth places the violin case on the rear cabinet and picks up a stack of his own records, including this one:

Predictable laughter after each of the next lines, as Rose says she has no idea what Procol Harum is and negotiates the definition with Ken. Even bigger laughter after Kenneth promises / threatens to spend the weekend listening to their records with Rose and Rose expresses her distaste for this possibility. There are some very realistic “baby boomer moments” in this section, as Kenneth mirrors the self-obsessed tendency of this group to think theirs was the only music ever worth listening to. He does this over Rose’s attempts to start a conversation about the conceptual point he raised — that classical and pop music are the same. She may be overplayed, but underneath the teenage aura there’s a person there, trying to talk about something meaningful. Kenneth gets all the laughs as he shouts Rose down. He detours briefly to rear stage left to yell up the stairs again that Jamie should be come down, before perching on the corner of the sofa just as Sandra (Amy Ryan) enters.

There’s a concrete shift in the atmosphere on stage at this point — the play becomes simultaneously faster and more bitter. Anything remotely young or half-baked about Sandra disappears from Ryan’s performance of the character in Act Two. If, in Act One, she seemed to feel the need to pacify Henry at times, or ease the atmosphere, that need is gone now; she steers every interaction and her demeanor, statements and delivery of the lines is so self-involved that it verges on narcissism the whole time and crosses the line toward the last third of the act. It’s only at this point, for instance, that Rose begins to hide behind the pillows on the sofa (see screencap below).

Sandra crosses to the table at stage left with a bottle of red wine and a glass and announces her thirst in epic terms. Kenneth rises to stand at an axis between the two. As soon as Kenneth and Sandra are both in the room, the use of Rose as bone of contention escalates drastically. Sandra interrupts Rose as she walks in; Kenneth points this out [laughter]; Sandra insists in the most lengthy possible way that she was not interrupting [laughter because it’s so obviously false]; Rose begins to speak again and Kenneth interrupts her [laughter]. Then Kenneth and Sandra spar in a friendly fashion about the need for a wine glass, with each line drawn out and laughter following each.

The way Kenneth is standing here gives a clue to Armitage’s physicality in the play — a very bluff, occasionally sarcastic, employment of comic stereotype.

Kenneth asks Rose if she wants a glass [laughter]; Sandra comments on Kenneth’s parenting [laughter]; Rose tries to get out from between them. Sandra suggests Rose wants a cigarette [laughter]; Rose is outraged [laughter]; Kenneth points out that she’s fifteen, apparently old enough; Sandra points out she’s sixteen [laughter].

Kenneth: “Sixteen there you are. We were drinking at that age, we drank for England both of us / you’ve told me the things you did” (p. 69). / here indicates the point at which Sandra interrupts with her next line, so the audience doesn’t clearly hear the material after the forward slash.

[Editorial comment: it’s a piece of British idiom that I always find amusing to hear — “we _____ for England.”]

We learn later in the scene that Sandra has had a bit too much to drink already this evening, and that explains the over the top way the next lines are delivered, with Sandra insisting that Rose does her drinking with her friends while Rose objects [laughter] and Kenneth agrees vehemently with Sandra that they are boring [huge laughter].

Sandra: “She doesn’t want to drink with us, she thinks we’re boring.”

Kenneth: “we are boring, that’s true!” (p. 69).

To draw out the point and the attention she seems to need, she compares them both to dinosaurs and begins miming the wing movements of a pterodactyl [huge laughter for her shrill cawing and her funny wing movements].

Kenneth calls up to Jamie again; Rose again refuses a glass; Ken wants the party underway; Sandra insists that Rose wait until midnight; Ken exits stage right rear to get a glass.

Now Sandra is seated at the table and Rose in the far corner of the sofa, behind the protective barrier of the cushions, as Sandra appropriates her for her own world picture as Kenneth did earlier. This time, however, Rose defends herself more aggressively. Rose tells her what flying dinosaurs are called [laughter]; Sandra mispronounces the name [bigger laughter]; Sandra admires Rose’s dress and Rose points out it’s a uniform [laughter]; Sandra accuses Rose of being in a bad mood and Rose says she’s not drunk but not unhappy — over-each-other speech that’s funny this time not so much because of what we hear but because they are clearly trying to outshout each other and then abruptly end at the same time.

Sandra stands and moves to center stage, where she excuses her constant interruptions of her daughter with tiredness. She then moves back toward the table where she sits. Her steps in this part of the scene are a bit uncertain — between extremely high heels and wine, she seems to be struggling to keep her cool. Now she objects to the look on Rose’s face, point out that adults have responsibilities. Rose (for the third time that evening) insists it doesn’t matter.

Responses to Sandra’s next speech again exemplify the different ways that the play could be played or understood. Here’s the plain text:

S: But obviously it does, it’s this huge rift between us tonight I mean I’d give you a hug but I’m not allowed to touch you anymore now that you’re a teenager. I know that you’re unhappy I can see it. I am concerned. But your father and me we work hard and sometimes these things can’t be avoided.

[Mike Bartlett, Love, Love, Love (London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2015), p. 71.

Straight this sounds like she is concerned. The way it’s played, it’s obvious that it’s about Sandra’s ego — she exaggerates every sentence, every moment of concern drips with sentiment in a way that makes it entirely unbelievable. But as before, when laughter vs. an outraged gasp signals the audience’s willingness to empathize with Rose, here the audience has a variable capacity to find this funny — but on the whole the audience laughs heartily at this over the top expression of motherly concern. Up until this point, Rose has very much been scoring the points for “annoying teenager,” but here the balance starts to flip.

Rose finds herself speechless, too, and Sandra tries to change the topic to the aforementioned Mark, but before she can, Rose again raises the topic of Sandra’s attendance at the conference. Sandra moves to the couch (stage left of Rose) to pursue the conversation. She seems to think she can force Rose to acknowledge that she was there but Rose refuses to say that she saw Sandra.

Next lines:

This clip gives a great sense of the exaggerated way that Sandra says everything in Act Two, her unsteadiness on her feet, Rose’s astonishment and the teenage awkwardness of her posture, and the bluff, comic physicality Armitage lends Kenneth. (His final line is really funny and for whatever reason it got cut off every time I saw the play. It’s too bad because it does say something about Armitage’s assertion that this play is about love.) As you can see, when Kenneth returns to the stage at this point, his suit jacket is off, too.

Sandra disjointedly returns to the subject of Rose’s violin playing, suggesting that she should keep it up. Rose is incredulous that Sandra doesn’t know her grade in violin [laughter], and Sandra gets laughs for her obvious line immediately after. (This line refers to ABRSM grades, a system of music examination originating in the UK and common throughout the world, but not particularly familiar to people in the U.S., so the information that Rose gives her will not say much specific to this audience.) Meanwhile, Kenneth is standing behind the table, stage left, noodling around with his arm as if he knows the answer.

At any rate, Rose has just said that she’s achieved a qualification equivalent to the A-level (she was graded “with distinction” — incidentally, here‘s the current grade six violin list) but not only do they not remember, they don’t remember although they went out for dinner together to celebrate. Ouch. But the audience keeps laughing.

Rose moves across the stage toward stage left, to sit at the front side of the table, sits down, hunches over in that inimitable way, and points out it doesn’t pay well. Sandra circles around her, insisting that Rose do something she loves, as Rose asks repeatedly (to laughter) whether they can just have the cake now. Sandra sits in the Wassily chair. Kenneth agrees with Sandra that they should wait, then he crosses to stage right (I think: behind the sofa and circling around it in front) and plops down in the corner that Rose has abandoned and puts his feet on the table. Kenneth — connecting touring with an orchestra to some of his and Sandra’s youthful exploits — begins to reminisce nostalgically about a hangover [laughter]; Sandra about almost getting murdered by an angry truck driver [laughter]; as Rose continues to ask if she may be excused [laughter] because she’s heard this story so. many. times [laughter]. Laughs as well for Sandra’s statement that Kenneth was her pimp and that her legs were good.

Kenneth jerks back to the topic of Rose’s music future. He makes a misquote, which causes Rose to rise and cross behind the table and over to the corner of the sofa to try to correct him. She is ignored (laughter). Then he reveals — with the same circular arm motion from before — that he’s already forgotten Mr. Parsons’ name (laughter). He also ignores Rose’s attempts to supply it (more laughter).

Then, Sandra asks what Rose is studying at A-level. Rose says “fucking,” moves forward to front center stage, and screws up her whole body as if she’ll have an apoplectic fit very shortly (laughter).

Laughs for Sandra and Kenneth’s slightly patronizing comments on her swearing, made in the tone of “our little girl!” Laughs for Rose (still in almost total physical outrage) pointing out that they’d talked about this last week and for Sandra saying “I can’t remember every detail.” Sandra gives a potted summary of how Rose’s life will be, says “I’m on a roll” (laughter) and implies she can do the same for Jamie, who needs to come downstairs (laughter). Kenneth yells yet again for Jamie (laughter). Rose repeats her desire to go upstairs. Sandra reproaches her for not enjoying their company (laughter); Rose says she wants to make a call; when Sandra points out the hour, Rose responds that her family is not in bed (laughter); more laughter when Rose refuses to tell Sandra who she is calling.

Sandra, who’s been refilling her wine glass periodically throughout the whole scene, is getting frustrated and rises to confront Rose — she moves to center stage, to stage right of Rose, while Kenneth moves stage left to get himself more wine and leans on the table to observe.

Kenneth tries to get Rose out of the line of fire, but Sandra isn’t having it. Replaying this part of the play in my head, it’s another one of those places where as an audience you could sympathize with either of them but their behaviors are so excessive that you just kind of keep laughing. One the one hand, Sandra’s ridiculous (laughter for her statements about how teenage rebellion is important, now is not the time for it though, your father and I made a real effort). On the other, Zoe’s so caught up in offended teenager mode (“when you came in late everyone looked!”) that it’s difficult not to laugh at her; although I’m personally sympathetic to her general issue (I remember family fights when I was in ninth grade about who was coming to my concerts or not), the fact that she is still pounding on her mother’s absence / lateness has become equally ridiculous at this point. Bartlett’s lines don’t give either character any quarter.

Sandra can’t respond to this charge, so she changes the subject, in a truly vicious, brutal way — she raises the topic of Mark, Rose’s boyfriend, and asserts that he flirts with her in the kitchen when he visits them. These lines offer another point where the audience loyalties fell either way; about half the time we kept laughing at Sandra and at Rose’s outrage; about half the time, there was “I can’t believe she said that” gasping and acknowledgement of Rose’s outrage. Kenneth gets a laugh for his attempt to tell Sandra to stop, as well.

I don’t remember exactly where these gestures went within this dialogue, but I’m including the caps just because we can see that Kenneth, even when he doesn’t have a line, is fully integrated in the scene by virtue of his reaction to what the women are saying.

At this point, the script turns Sandra into an out-of-control concern troll and as her backhanded compliments continue, it’s clear that she doesn’t see her daughter at all. Laughs for “I’m not bothered”: “it’s understandable, boys like real women at that age”; “don’t get attached.”

Important to note for purposes of this later plot at this point: Rose comes straight out and calls her mother a bitch (laughter, laughter bordering on applause some nights). Kenneth moves to front stage left to agree with Rose and gets even bigger laughter. But it doesn’t stop Sandra: laughs for patronizing comments about Rose’s swearing. Sometimes laughs, but mostly a gasp for Sandra’s “you’re pretty — when you try” comment. Sandra tells Rose she should be having fun; outraged Rose says “like you had fun you mean” (laughter) and again “fucked around a lot, did you” (laughter) and “now you think I’m hung up on sex!” Sandra expresses concern and Rose wants to know what she means, and the whole machine stalls for a second until Sandra returns to a statement about what a great mother she is (laughter some nights, gasps others). Kenneth makes his third attempt to get Rose out of the room, and is finally successfully. Rose very comically sits her but on the floor to put her shoes on, gathers her things, and then moves to the rear of the stage, where her huffy posture, adenoidal tone, and craning neck add to the impact of her request that her parents not shout while she is on the phone “cos you do sometimes and it’s embarrassing” (p. 78). Uproarious laughter — and a little sigh of relief, some nights — when she exits at rear stage left, stomping up the stairs.

This is halfway through this act and I am going to stop here for a bit, to chunk this up in terms of readability. It’s also a caesura in terms of audience reception, since the remainder of the script is hard to laugh at. If the audience is laughing really hard at this point, still (and not gasping or oversympathizing with Rose), then the arc of the act works. If not enough laughter is happening by now, the last twenty pages have a very different effect.

Continues here.

~ by Servetus on November 27, 2016.

Posted in Richard Armitage

Tags: acting, Amy Ryan, Ben Rosenfield, comedy, generational conflict, Jamie, Kenneth, Love Love Love, Mike Bartlett, Richard Armitage, Rose, Sandra, Zoe Kazan

12 Responses to “Love, Love, Love: Attempt at description, Act 2a [spoilers] #richardarmitage”

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

[…] [Continues here.] […]

LikeLike

Love, Love, Love: Attempt at description, Act 1 [spoilers] #richardarmitage | Me + Richard Armitage said this on November 27, 2016 at 8:18 pm |

Tiny correction: Schulranzen

LikeLike

Thanks, fixed.

LikeLike

I read the play. This is so interesting. I could not fathom where anyone would laugh. You have brought it to life off the page for me.

LikeLike

Thanks. I’m glad it’s useful — because this part was hard to write. I couldn’t entirely figure out how the first part of this act was really organized, and that meant it was just exposition. Kind of tedious to write.

LikeLike

[…] reference to poll tax in first half of Act Two— I mentioned that the line more or less goes under. But in talking another friend tonight […]

LikeLike

Footnote | Me + Richard Armitage said this on November 28, 2016 at 2:26 am |

[…] from here. Be aware of previous […]

LikeLike

Love, Love, Love: Attempt at description, Act 2b [spoilers] #richardarmitage | Me + Richard Armitage said this on November 29, 2016 at 2:52 am |

I am finally getting to read this. It is interesting what you say about the mood in the room. I recall the audience in Act Two to have been fairly light hearted in spite of the subject matter.

Regarding Rose, who is the real star of this Act: my own impression was that Rose was a stereotypical teenage girl, with high drama, and that was funny, especially since the thoughtless things her parents were saying were somewhat typical. That is, until things turned dark and then you realize that she had good reason to be hysterical. I agree that she acts young — I spend a lot of time with 15 and 16 year old girls, and they don’t act like this. To me, she behaves more like 12 or 13, or at least how my daughters were at that age. As I’ve said before, I didn’t like Zoe Kazan’s portrayal of Rose in this act. I think if she had just toned it down slightly, I might have liked it, and as a former teen girl, I should have been able to relate to the pain of her situation. But she was too shouty and overwrought and so the subtler things she was doing got a bit lost. At one point, she stormed off the stage to go to her room with fisted hands and shoulders rolled as far forward as they could go, and it looked like stage direction rather than a posture of a real person.

The three most cruel and memorable lines from Act Two: (1) Jamie telling Rose that her boyfriend was having sex with someone else; (2) Sandra’s comment about Rose being pretty when she tries; and, (3) Sandra telling the children that their parents were getting a divorce, even though Kenneth and she had not discussed it (probably you will mention this in your next post — you mentioned the other two above). For these, the audience was somehow appalled, but for the rest, there was lots of laughter. For the cake scene, the audience was in true hysterics.

There were no ushers standing in front of the stage at my early October showing, so I’m wondering if something bad happened.

LikeLike

Yes — as noted, this is the first half of Act Two.

re: Kazan — I made a post that’s essentially just a commentary on Act Two that explains my perspective on why Rose needs to be played in such an exaggerated way for the play to work. But I don’t think we’re supposed to like her.

I don’t know that anything bad happened. The ushers appeared at front for the first time some time in the first week. Almost all the ushers are volunteers, so perhaps they just don’t always get the personnel.

LikeLike

I’ll read your commentary next. Thanks for doing this. I still have pretty vivid memories of this play two months later, but I usually catch something new when I read your posts.

By the way, I thought Kenneth had better intentions in his interactions with both of his children in this Act than you did. I felt he was genuinely trying to connect with Rose because he realized that her concert was important to her, even though he said a bunch of stupid things. And there were some parts of his discussion of music with Jamie that seemed like he was remembering being a teen boy and trying to make a connection. I don’t think he was successful — he is too self-absorbed to really understand what is going on in his children’s lives — but I did feel like he was showing some empathy. I thought it was more about them than about him trying to get them to like him. In contrast, Sandra’s attempts to connect with her children still felt like it was all about her. Her intention seemed to be more to justify her behavior than anything else.

I kept wondering if I liked Kenneth sometimes because I like Richard.

LikeLike

I think a lot of how we read this scene overall has to do with the fact that we cut men slack over their parenting that we do not cut women. (What that means, however, can be complex.) I agree that Ken appears to be trying harder in this act than does Sandra and he seems to be more aware of his daughter’s feelings for sure and possibly of his son’s. (He’s hampered with regard to Jamie because Jamie doesn’t really respond / give indication that he finds amusing the banter that Ken starts with him. It’s potentiallly more serious that Ken can’t really “see” Jamie, as we find out in Act Three.) But we expect so much less from men — we expect them to stay stupid things. (I think the whole issue of not knowing how old his daughter is exemplifies this quite well — if that exchange had been put in Sandra’s mouth it would have been hard to read that as evidence that she was “trying”.) In contrast, Sandra obviously breaks every rule about good parenting and does it in the most bombastic, declarative way possible — but we are ready to hold her responsible for it.

re: liking Armitage vs. liking Kenneth, I do think that plays a role, but I think he’s just too lazy to be as unlikable as Sandra is. He’s not an active author of havoc on a comparable level. (Then again — we should probably ask ourselves: why do we demand more from the woman? Why is it a problem if a woman is active as opposed to passive? Why don’t female characters get cut the same slack as male ones?) I think Armitage is good as Kenneth but he never brings to me really like him. I think he’s funny, sometimes, and I’m briefly sorry for him in the middle of this act (which maybe says more about his acting than is completely obvious as I find infidelity inherently unsympathetic).

My reading of this play is certainly influenced by the fact that I am living with my elderly father and some of Kenneth’s lines could have come straight from my father’s mouth.

LikeLike

[…] now that I’ve documented what I saw in general terms (Act One, Act Two [part one, part two], Act Three), I can drop my more personal impressions from the trip via my diary on […]

LikeLike

Performance impressions, Love, Love, Love 11/3-11/6 #richardarmitage | Me + Richard Armitage said this on December 11, 2016 at 8:06 am |