Religion, superstition, piety, belief: me + adrian schiller in The Crucible

This post had been on my “to write” list since the first time I saw The Crucible, but it’s been hard for me to express everything I felt about Richard Armitage in it, let alone get to other things. So something I had really wanted to do — document at least a little the work of the supporting actors — has fallen by the wayside. (Natalie Gavin: this means you. Someone needs to write about you.) It feels like time to write a little about one of them tonight: Adrian Schiller, who plays Hale — the witchcraft expert called into Salem in order to figure out what’s happening, who observes events and gradually realizes that he is implicated in, and partially author of, a massive injustice. Among the many moving performances audiences were treated to in The Crucible, Schiller’s was one of the strongest. He deserves recognition for a bravura (and very emotionally exhausting) performance — for me, not least because Hale is one of the roles I find most crucial in making sense of the play. Schiller’s moving embodiment of the troubled clergyman adds sensitivity to a play that I find tone-deaf about the appeal of religion in general and the matters that bound its contemporaries to early modern religion in particular.

[If you want to read my comments on Schiller’s performance, and not my reflections on the problems the play sets up for the character he plays, skip down two headings.]

First, a detour about the theme of religion in the play …

It was not Miller’s obligation to seek to understand either of these things, since, seen historically, The Crucible is a play about HUAC, the “red scare,” and state disciplining processes in modern mass societies, and not really about Salem, which serves as a symbol for what Miller really wanted to discuss and shows stronger parallels to the U.S. 1940/50s in the area of social disciplining. When LondonFriend learned I’d be coming to see the play myself, she mused that I was perhaps the person she knew to whom the play’s commentary on religion might mean the most, as I’d had the most traditionally religious upbringing of anyone she knew. Strictly speaking, though, as hyperreligious as my childhood was, I’m still separated from Salem by the Enlightenment. Even as a child I was firmly aware — even if we sometimes chose to ignore it — that boundaries between the natural and the supernatural structured my world in ways mostly unknown in New England in the 1690s (and which I didn’t even learn existed until graduate school).

Abigail Williams (Samantha Colley) tells Betty Parris (Marama Corlett) what she must not confess, in Act One of The Crucible. Source: screencap of DigitalTheatre vid.

So rather than admiring the script for its takedown of traditional religion, I struggle with the condescending attitude it invites the audience to take toward its own fun-house mirror of early modern belief. A perfect example of this problem appears shortly after Hale enters Act One: Upon learning that the girls Parris saw dancing in the forest had been making a soup, Hale asks whether various sorts of living creatures had been near it (for history buffs: he’s asking about a familiar), and Abigail replies that it was a frog. The London Crucible played the lines here slightly differently from the exact language in Miller’s script, but the effect is the same. On almost every night I saw the play, the audience laughed at the characters’ folly. How could anyone believe that the random presence of a frog had anything to do with the presence of Satan? This moment has often felt cheap to me.

To contribute to the discussion of the permissibility of laughing while watching the play, by the bye: I hypothesize that Miller meant moments like this and others similar — where the characters negotiate over various signs of witchcraft — to offer an opportunity for laughter. During a play that becomes inexorably darker and narrower, the opportunity to lift the shoulders and air out the lungs is unquestionably a relief. (How the actors handled audiences’ tendencies to do so in London was a different question — at times I felt they were playing too fast to allow the audience to respond with laughter for fear of losing something.) To be fair to Miller, these moments could lull the audience into a belief that they were fundamentally different from the Salemers, who saw the Devil in a misplaced frog or believed that screaming in response to hearing G-d’s name testified to a demonic presence. If that worked, the growing awareness throughout the play, as Richard Armitage alluded, that its spectators are themselves implicated in the kind of judgmental social disciplining that the play criticizes would eventually choke such laughter in the audience members’ throats. Miller’s intent, I believe, was at least partially that we realize we are just as cruelly narrow-minded as the characters we watch on stage and laugh at betimes.

Mary Warren (Natalie Gavin) confronts a possessed Abigail (Samantha Colley) as Proctor (Richard Armitage) and Reverend Parris (Michael Thomas) look on, in Act Three of The Crucible. Source: Geraint Lewis Collection

That result was exponentially more likely to materialize in the Crucible staging at Old Vic than it would be in a traditional proscenium, as Armitage said they had expected for the production, because those seated in the expensive seats inevitably one found themselves at least glancing at other audience members across the round, even if only for a split-second. Still, I believe it is not a lesson that most readers or spectators draw from this play, mostly because this summer I read comment after comment that pointed in other directions. What The Crucible might tell us is that we are more like these people than we realize, and that if we had lived in the seventeenth century, most of us would have urged the hanging of witches just as the Salemers do. In contrast, I think most viewers conclude that we must preserve freedom of thought and keep religion out of politics — both laudable conclusions, but beside the point, for me, anyway. John Proctor’s story is more than the tragedy of a heroic martyr to conscience — it is also, as Miller’s remarks in the original script make clear, and Armitage’s slightly later comments suggest that he fully understood, the story of the destruction and (self-)punishment of a hypocrite. It is, and should be, hard for the watcher to admire Proctor.

And then about the character of Hale …

The officials of the court, including Adrian Schiller as Reverend Hale, in Act Three of The Crucible as staged at the Old Vic, summer 2014. Source: Geraint Lewis Collection

If The Crucible is to escape interpretation as a bald allegory about how silly it was to burn witches, or why we shouldn’t persecute people who think differently, or on a more sophisticated level, why theocracies are dangerous, even to their most virtuous supporters, much weight must be given to the way that Hale is played. The role is crucial for two reasons. First, Hale balances between all of the poles of the play. He is both religious and learned in religion; he believes in the supernatural and yet understands from the beginning that much of what the Salemers want to attribute to the Devil could be coincidence; he believes that religion defines virtue through Scripture and the effects it produces in the faithful (attendance at meeting, for instance) and yet knows that pieces of virtue exist that can only be understood via experience and which stand outside of the capacity of religion to encompass them. Hale supports the authority of the court over the Salemers by participating in it, and yet knows that the state is capable of erring, even if G-d is not. He mediates between Parris’ rigid orthodoxy and fear and the less well-defined quality of the Salemers’ religion, between Danforth and Hathorn as legal authorities and the Salemers as subjects of the law.

Reverend Hale (Adrian Schiller) witnesses John Proctor’s (Richard Armitage) frustration with his inability to remember the last of the Ten Commandments, in Act Three of The Crucible. Screencap.

Hale begins the play as more expert than everyone else in both the abstract and applied senses — as practitioner of care of souls in a very concrete way. In Act One, he tries to help both Betty Parris (Marama Corlett) and Tituba (Sarah Niles), with uncertain results. Once the Putnams’ surviving child is reported possessed, however, a court is opened in which Hale participates, now drawn into the affair in a much more concrete sense as he eventually will sign death warrants. Under the implicit understanding that those who are not guilty have nothing to fear, he first urges submission to the procedures of the authorities. In Act Two, he does this after he learns during an evening visit to their farm that John Proctor cannot recall all ten commandments and that Elizabeth Proctor (Anna Madeley) believes that someone who does good deeds and tries to live a good life cannot be a witch — and witnesses the bailiff taking Elizabeth away after she had been accused in court at a time when he was away from it. But as the trial continues in Act Three, Hale eventually abjures the proceedings, to spend his time, as we learn in Act Four, counseling the condemned and trying to get them to confess (even if falsely) to save themselves from the gibbet. Whether is a step he takes to keep his own self-concept intact is a matter we could debate, but in the end he certainly regrets his role in what has gone before.

Hale (Adrian Schiller) watches as Proctor (Richard Armitage) ends Act Three of The Crucible in a flurry of self-accusations. Source:

In that sense — although I know it may be potentially heretical to say this — the second reason the role is crucial is that Hale is much more important for the audience as witness to the events of the play than Proctor, who changes very little from the beginning to the end of the play. Hale makes the journey that I believe the audience is supposed to trace itself, from a belief that maleficium is a crime and that one can assess a source of blame in witchcraft cases to an awareness that the charges are hopelessly tied up in community problems and relational politics both large and small. Over the course of the second half of the work, Hale develops a growing horror at the travesty of larger justice that unfolds in the realm of the adherence to procedure practiced in the court at Salem, and recognizes to his his disgust that the only way the victims can be saved is if they give up precisely the rectitude that causes them to accept execution as a consequential end to their lives.

Dramatically, this step works if Hale is played as if he believes in something akin to the way the Salemers believe but also stands far enough outside of their world that we can identify with him as spectator. So many manifestations of religion populate this play, if in many cases inadvertently, from the villagers’ ritualistic and prophylactic responses to what they think is maleficium, to the Putnams’ posturing; from Parris’ (Michael Thomas) embattled sermonizing in the context of disputes over his remuneration to his niece Abigail’s (Samantha Colley) revolt in the forest with her friends against the exploitative treatment of her neighbors and the strictures applied to their behavior; from Elizabeth Proctor’s self-righteous dogooding to Proctor’s inability to overlook the golden candlesticks in the meeting-house; from his own notion of religion as the science of a knowable world to Danforth’s (Jack Ellis) understanding of religion as a force of order. Someone must allow us to see and compare all of these, and the character that stands outside and inside, comprehending and mediating — it’s Hale.

Adrian Schiller as Hale: What impressed me

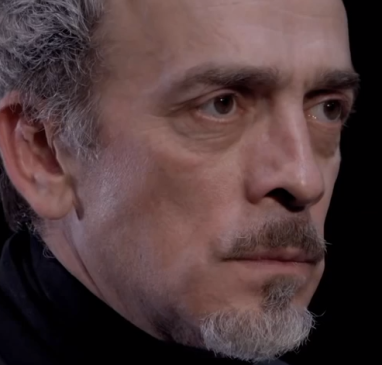

Closeup of Reverend Hale (Adrian Schiller) as he witnesses Proctor declare that G-d is dead, in Act Three of The Crucible. Screencap from trailer for The Crucible on Screen

From the first step he makes onto the stage, Hale’s mien as a Puritan clergyman impressed me. Hale enters with a stack of heavy (theological) books and asks someone to relieve him of them. When Parris responds that the books are heavy, Hale replies, “they must be. They are weighted with authority.” And the audience almost always laughs. Miller has Parris reacting to Hale (in the stage directions) with a certain amount of fear, but that wasn’t how this was played at the Old Vic — and this divergence from Miller’s stage directions was crucial. With a statement that can be interpreted simultaneously as literally true (and Hale’s lines follow up the seriousness of studying the sources to know what he is encountering) but also slightly self-ironic, Schiller’s Hale whose authority vests at least in part in his studiousness and humility of posture represents to the audience precisely the insider / outsider position that is so crucial if we are to see the developments of the play through his eyes. Protestant clergy were also masters of theological jokes, and this tendency goes back to the beginning of the tradition; plus Schiller gets potential plus points here for fully inhabiting the gravity of the Puritan minister and the slight world-weariness — for Puritan divines were characterized in part by their own spiritual struggles, and both the way that Hale delivers this entry line and the way he carries himself throughout the play, as low status in comparison to every other male character, emphasizes both his authority and his awareness of his fragility.

Reverend Hale (Adrian Schiller) convinces Tituba (Sarah Niles) that she can save Salem if she confesses, in Act One of The Crucible. Source: screencap of trailer

As Miller notes in his original script, at the beginning of the scene, Schiller acts a bit like a doctor on a house call, and this piece of the scene isn’t hard to play, I suspect — he does have all those books and all of that knowledge and he’s dealing with villagers who are largely untutored, beyond common knowledge, about what they suspect they are encountering. The part of Act One that looks hardest to portray, in my opinion, occurs after Abigail, under pressure for dancing and souping, accuses Tituba (Sarah Niles) of calling the Devil. When Tituba refuses to confess to this charge, Parris threatens to whip her to death and Putnam (Harry Attwell) moots hanging, after which she wisely maneuvers herself so that she isn’t the chief malefactor by participating in Hale’s movement of her body and soul toward a Great Awakening-style “come to Jesus” moment where she both states her love for the children and accuses four Salem women. This point of the script is tricky, because although it seems at the beginning and perhaps at the end that Tituba is confessing simply to avoid violence, it is clear that at least some participants in the scene — and at times Tituba as well — are caught up in the ecstasy of the moment of conversion (or at least confession of conviction). This atmosphere persists until Abigail decides she needs some more attention, and breaks in with her own series of confessions and accusations.

It would be tremendously easy to get this wrong and I wonder if I would view the play as positively as I do had they done so. This is a moment where Schiller’s Hale simply shines. He has two things to communicate here — his absolute belief that the Devil is present in Salem and that the problem can be addressed through Tituba’s help, and his awareness of his superiority to Tituba in understanding what is actually going on — with his connected willingness to be the only person in the scene who is not holding her at fault. Tituba (Niles) is in a complex situation where she enters the dialogue over witchcraft in order to save herself from certain violence but gets drawn in by Hale’s manner. It is crucial that Hale be absolutely convinced, absolutely embedded in this miscrocosm of spiritual combat and personal conversion that he creates with Tituba and that he not overplay it in a way that makes us connect it with the excesses of evangelical preachers of conversion who have, for our eyes, become the object of derision. He also has to overlook the problem that she is inherently the weaker partner, and as a slave,[see footnote] not able to exercise agency in the sense that a true conversion would seem to require. Schiller’s Hale never breaks — he is absolutely caught up in his own natural / supernatural world, both put into motion by belief but also bounded by a solidity that keeps him from make us laugh at him — and so are we. In case you are wondering, I did get a chance to talk to him at the stage door and told him this, in much less detail. I said that as a religious person, I didn’t feel as dissed by this staging of the play as I often do, and that was owing in large part to his sensitive portrayal of a divine who has a calm, even humble belief in what he is doing. I also said something about his use of his hands; see below.

Hale (Adrian Schiller) looks on in pain as Proctor (Richard Armitage) rips his confession in half, in Act Four of The Crucible. Source: Unknown

Hale has a lot of great moments as an increasingly frustrated member of the court and mediator for Proctor and Giles Corey (William Gaunt) in Act Three, but the final place where his portrayal truly impressed me was Act Four, in which a shaken, haggard, frightened Hale is desperately trying to wring confessions from the prisoners in hopes that they will not go to their deaths (on the warrants he has signed). In the end, he is suspended between precisely the poles he has balanced out before — (authority) Danforth will not budge; (traditional morals/virtue) Elizabeth will not urge her husband to act against his conscience; (the tantalizing virtue outside of religion) Proctor, after initially signing a confession, admits it is a lie and refuses to recant his recantation.

In the end, the one who actually feels he has blood on his hands is Hale. His sheer desperation as he moves from argument to argument, as his hands shake, at the beginning only slightly, and as the scene progresses inexorably to its end, ever more, offers a masterful indication of his disintegrating mood and his increasing recognition that he, too, must count himself among the damned.

***

*****FOOTNOTE and CAMEO: [I need to mention in passing that the decisions made around the portrayal of Tituba in this play really deserve a solid picking apart. Sarah Niles masterfully and fully inhabits a persona that for my taste shaves frighteningly close to a severe and near total racial stereotype. She has a mesmerizing ten minutes at the beginning of the play — which I gather has been either cut out or shortened for the screen version — but after that, I felt wildly uncomfortable watching Niles do this, on the order of how I squirm when I see historic film footage of blackface, and maybe that was Farber’s intent, since she spoke so frequently about the evils of apartheid in her interviews around the play. However, remarks made by fellow theatergoers in the stage door line suggested that they saw nothing either stereotypical or troubling about this particular way of playing the character, which is in itself frightening. And I’m willing to concede that my reaction may stem from deeply entrenched American white liberal guilt and that UK audiences might see this quite differently. Something to think about when we can see it again. In any case, how we understand this scene corresponds strongly to what we see Tituba as doing in these interactions, and I had to flatten that out for this analysis. I just didn’t want you to think I was ignoring it.]

Good morning !

Thank you for the writings.

It will help me to study the Crucible’s english and french old books (1969). I borrowed them from the library last saturday for a month.

Until the movie come in France in march , I am going to work hard like a student, exploring your previous text analysis too .

I have not yet seen the stage play .I am looking forward to it and perhaps to be able to write something of interest afterwards.

On the over hand these are some bricks foundations , you spoke about and I waited for . I am so thankful to you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad it helps. Miller’s language takes a lot of license, so I’d definitely suggest reading it in French first to make sure you understand what’s going on before exploring the language. I saw lots of fans in that theater with books / scripts along with them, which they were reading before the show and in the intermission. So you are not alone.

LikeLike

Hello!

Pour la traduction de la pièce en français, il faut noter que c’est plus une adaptation (par Marcel Aymé) qu’une réelle traduction. Il y a de nombreux passages de la pièce qui ne sont pas retranscrits sans parler des didascalies….

Je dirais que nous avons une …version très différente avec le texte français (et datée, voire vieillie) même si elle reste intéressante.

By the way, Servetus, I will read your post with more attention when coming back from work ^^ I have to go ….

LikeLike

Hello, LadyButterfly,

Je l’avais remarqué dès les premiers coups d’oeil en diagonale .

Les bibliothèques françaises offrent des pépites.

Il s’avère que le CEB Classique Etranger Bordas de 1969 de Boitier, est un meilleur outil de travail , bien qu’il soit en partie en anglais et édité avec des caractères d’imprimerie minuscules .Dur, dur , je devrais changer de lunettes .

Il y a le contexte historique, la biographie, l’oeuvre de Miller, les thèmes soulevés par l’oeuvre. De plus de la grammaire, de la prononciation, des exercices , des rélections , des apartés . Un vrai bouquin antédiluvien pour étudiant en anglais quoi !

Dans quoi je me lance ! Moi, une férue en physique- chimie et bio, qui boycottait les cours de français, alors la littérature étrangère …

Où la “fan-attitude” m’embarque t-elle !

De toute manière ces 2 livres n’offrent que des extraits de la pièce de théâtre. Mais il faut bien commencer par quelque chose, après le streaming du film américain , la lecture de la version de M Aymé… Si vous avez une meilleure référence à me proposer, je suis toute ouÏe.

Encore mille fois merci

❤ “Armitagement votre”

LikeLike

Non, il n’existe pas d’autre traduction, française, tout simplement ^^

Intéressant également de visionner le film réalisé avec S.Signoret et Y.Montand d’après la pièce en français: “Les sorcières de Salme” donc, pour nous, d’après l’adaptation de M.Aymé (on le trouve en version intégrale sur youtube).

Sinon, pour lire la pièce en anglais, le plus simple est de commander le livre (très facile, on en trouve d’occase sur les sites web).

Je rigole parce que mon édition en V.O de “The Crucible” avait aussi une police de caractère tellement petite que même mes lunettes étaient à peine suffisantes …..

🙂

Allez, bonne lecture!

LikeLike

I would guess that it would be very hard to translate this play.

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow, großartige Betrachtung des Charakters,

das Problem ist, wenn frau den Focus nur auf einen bestimmten Schaupieler richtet – wie bei mir – gehen die anderen leider etwas unter, falls ich das Glück habe und das Stück nochmal sehen darf werde ich ‘versuchen’ Hale etwas intensiver zu betrachten. Danke!

LikeLike

Unbedingt Suzy. Der Typ ist eine Wucht!

LikeLike

it is a problem. I was lucky to be able to see it so many times consecutively and just because of that I owe it to make sure I preserve my impressions somewhere, I think.

LikeLike

Wie schön Serv, daß du mal 2-5 Sätze (oder etwas mehr) zu AS gesagt hast. Ehrlich gesagt hat mich seine Wandlung und Zerissenheit im Sommer fast mehr gepackt, als die sture Verzweiflung von JP. Allerdings war das auch sicher dem Umstand geschuldet, dass ich die Eindrücke inkl. die unmittelbare Präsens meines hust Lieblingsschauspielers nur wie im Schockzustand aufgenommen habe. AS zu beobachten war jedenfalls vollkomen stressfrei möglich und somit ist mir seine Darstellung sehr nahegegangen. Ich fand es ebenfalls sehr beeindruckend, wie “ernsthaft” er mit dem Thema Hexerei umgegangen ist. Er war zu jedem Zeitpunkt ein mitfühlender, verständnisvoller und komplett überzeugender Akteur in der Interpretation seiner Rolle. Ich mochte ihn eigenlich ständig, trotz der aus unserer heutigen Sicht Fragwürdigkeit des Themas. Und ihn dann am Ende so verfallen zu sehen, war schon hart. Er stand da dem JP (in seinem zerissene Leibchen) in nichts nach.

re. Leibchen: Hat sich eigentlich mal einer Gedanken gemacht, warum das Hemd von JP nach nur 3 Monaten schon so dermaßen zerlumpt war? So wie das aussah, hätte er breits 3 Jahre im Gefängnis verbracht haben können. Aber das nur am Rande 😉

LikeLike

Rats. They were chewing on it while he slept.

Actually, I have no idea. Although early modern prisons were no fun.

LikeLike

Honestly, I think it was for more dramatically reason. And to add the “sexy” image of one of his nipples 🙂

LikeLike

oh, and I’d need to look this up again but iirc, the Salem prisoners were not kept in a jail because they didn’t really have one. I think they housed them in the cellar of their townhall or something? In any case, overcrowded and substandard, even for the 1690s.

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading your thoughts on Hale. as someone who hasn’t seen any production of this play, let alone the recent London one, and can therefore only create impressions from reading the play itself- It was Hale who held my attention throughout most of the story. his responsibility, both from a professional religious/legal point of view and a personal one, was fraught with multiple implications that left me all mixed up inside. John’s story, while full of weighty themes of it’s own, seemed more straightforward to me.

LikeLike

I agree fully with this comparison. Which isn’t to say Armitage isn’t great in the role, or there’s nothing interesting about Proctor, but there’s much less transformation going on there and what there is we kind of don’t see much of. He leaves the stage angry and frustrated at the end of Act Three, dragged off, and then enters Act Four after several months of jail, changed, but it’s hard to see exactly how.

LikeLike

Fantastic, Servetus. I did see Adrian Schiller having a smoke outside The Pit Bar with Natalie Gavin one Saturday night, but as it wasn’t the Stage Door, I didn’t want to intrude on their privacy. I believe all I said was “You were both incredible” or something like that… glad you had the chance to convey a little more about what was so wonderful in his performance. I agree, he was a very sympathetic character for me, as well, because he seemed to be one of the few people in a position of authority who actually cared about the spiritual welfare of the town, from the beginning through to the end. Everyone else had other motivations, but he cared, he conveyed that he cared, and it broke him in the end.

Hope you will indeed blog about Natalie Gavin as well… she impressed me so much with her performance, most especially in Act 3, but until I have a chance to watch the DT version, I don’t have great notes to be able to compose everything that I loved about her performance.

Re: John Proctor and it being hard for the watcher to admire Proctor… in some sense I agree with you, but he totally redeemed himself for me in Act 4. Not because in the end he chose to go to his death rather than sign his name to the confession, but because of what he said to Elizabeth when he was explaining why he would confess… “Nothing’s spoilt by giving them this lie that was not spoilt long before”- acknowledging that he’s a sinner, and that to go proudly to the hangman like Goody Nurse would be yet more hypocrisy and wouldn’t fool God. And later, when he said “I am not worth the dust on the feet of them that hang”- he redeemed himself. I admired him and fell in love with the character at that point. Sigh.

LikeLike

I just can’t bring myself to find someone who chooses to die in a situation like that, voluntarily, admirable. I know that is the conventional view and I know that many people feel that way when they see the play, but I struggling with the idea that (what is in my opinion) an unnecessary death should be redemptive.

LikeLike

I admire the concept of what John did and I can applaud him for it, as a fictional character, b/c he knew what was important to him and didn’t sacrifice his beliefs against his will. but when I look at it in a realistic light, as him representing a real man, I get angry with him. he had a wife and children who depended on him, especially in that time period, and if he really wanted to fight against religious tyranny, sacrificing his personal respect could have admirably been traded for sticking around to fight in more productive/lasting ways. if he didn’t have family dependents then his life would be entirely his own to do with as he pleases but as a husband and a father it was selfish in some regard

LikeLike

and there’s a level on which — if Armitage is right about something in Proctor representing a cri de coeur of Miller’s (and he’s not the only one who thinks that; Miller’s most important biographer thinks so too; I don’t know if Armitage read it there or came to that conclusion on his own) — choosing execution in this way is almost (dare I say it) self-indulgent.

LikeLike

going back to your comment about redemption: I didn’t see John as accomplishing any kind of redemption in what he did. this seems to be the general opinion of the conclusion to the play (that giving up his life was a fair trade, somehow). John had an affair with Abigail during his wife’s illness that he greatly regretted and was struggling w/the consequences of but I don’t think his final decision in prison helped him achieve redemption for that- unless one equates redemption with punishment, which I do not. in this instance I do not think John was sacrificing his life for someone else or even for the greater good (as per my understanding of redemption) b/c he didn’t think his life was worth that. but rather it was a choice between choosing truth- as represented by death and guarding against tarnishing his name further- or choosing the safe/coward’s way out by staying alive and supporting a lie (the accusation of witchcraft). I may be off base in my understanding of the story though, since I’m not entirely familiar with the play or it’s modern history, having read it in High School originally and then revisiting it briefly again this past summer.

LikeLike

Whatever we conclude about the meaning of redemption I think it’s correct to say that at least one question we have to ask is: what exactly is John dying for? If his name, then is he really going to the gallows because he lied about his adultery? Is that what he’s being punished for? Because that is a self-punishment that is quite disproportionate to the crime.

LikeLike

I think he was fighting for his name in sake of his children, but dying as punishment for adultery does not seem to fit the crime for me either. I think he was punishing himself out of shame, trying to do the right thing this time to make up for the wrong thing he did before, “two wrong things make a right”. I have a hard time coming to terms with that way of thinking though b/c the two wrongs aren’t relevant to each other.

LikeLike

I think you could make an argument that he’s trying to prove that the authorities (state/church) can’t move him to lie anymore … that might be redemptive (he finally figured out who he is) on a sort of individual level.

So often with this play, I feel, Miller got carried away with his dialogue in ways that sort of make it hard to understand what he was trying to say in a bigger sense.

LikeLike

i.e., what does have to redeem, be redeemed from?

LikeLike

I totally agree… what I loved was when he acknowledged that voluntary death, for him, would be hypocritical. Then he ended up doing it anyway, which I’ve always felt was a poor decision, and had he been my husband, I’d have resented it. Elizabeth made it clear that she would support either decision, which was very noble on her part, though again, not what I’d have said to my own Hubby, assuming he’d survived my finding out about his infidelity =). That said, from a literary standpoint, the decision to go to his death honorably rather than live a lie leaves a huge impact on the viewer. If the play ended with him signing the confession as planned, it wouldn’t be nearly as monumental of a climax. I’m trying to think of ways that it could still end with a climax if he’d signed the confession, and am drawing a blank =)

LikeLike

deciding to go to his death honorably made a huge impact on me and is what really sticks with me about his character. I respect him immensely for that decision; I find it very brave. if he did end up signing the confession though, I doubt I would even remember John Proctor.

LikeLike

impact on the viewer: I agree that it would be a less climactic ending if he had decided to live. The problem is that the play has never really made sense to me, and this is one reason: because it feels to me like he goes to his death primarily for effect.

LikeLike

Thanks for your analysis on this.

While I admired his acting in the play, for some reason I did not delve deeper in the role he represents (for the other people in the play, for the spectators) or the changes he suffers in the course of the events.

I put more thoughts on Proctor, Abigail, maybe even Mary and Elizabeth, but Hale was a void.

I have to train myself to keep an open eye to all of the characters when reading a book/play or watching a movie/play which is a bit difficult if you are not living in an academic environment (but I am trying…)

LikeLike

I think part of the reason you don’t pay as much attention to Hale is that the character himself is always watching, when he’s in the scene — a lot of what he does is simply to witness what other people are doing. Not that he doesn’t have significant lines, especially in Act One and Act Two. But he spends a lot of time watching.

LikeLike

Thanks for writing this. I was totally impressed with Adrian Schiller when I saw him live on stage in London and I felt a little bit sorry after watching the play on screen, because for me the filmed version wasn’t able to do him justice

LikeLike

I’m sad to have to agree with that evaluation after seeing it on my screen. He really lost a lot in the screen adaptation, I feel.

LikeLike

Glad someone else feels the same. Thought I’d imagined it…

LikeLike

After (finally!) getting to watch the video, I came back to re-read some of your posts, and this makes me wonder – when Hale came on in Act IV with his hands shaking, he had me in tears – I can’t imagine how intense this must have felt live, if the recorded version takes anything away from his performance.

LikeLike

he was just really excellent as the witness to stuff that happened. And best of all in Act Four, I thought, whereas the video did cut some of that effect out. He was the actor with whom I had the longest conversation — and you also realize, wow, he really is acting … so talented.

LikeLike

[…] a general review of Richard Armitage’s performance in the play. Here’s a general review of Adrian Schiller’s performance in the play. Here are posts where I discussed Armitage’s performance of virility as John Proctor, and his […]

LikeLike

Nipple, nipple, nipple! I’ve been informed that I’m not taking The Crucible on screen seriously enough | Me + Richard Armitage said this on March 21, 2015 at 7:13 pm |

[…] you know, I’d commented on Schiller’s performance before, at length. This is probably my favorite interview from this series so far (with apologies to Richard […]

LikeLike

Adrian Schiller on playing the Reverend Hale in The Crucible (Digital Theatre Plus interview) | Me + Richard Armitage said this on April 13, 2015 at 2:23 am |

[…] Schiller played Reverend Hale in The Crucible — I really loved that performance. […]

LikeLike

Richard Armitage degrees of separation | Me + Richard Armitage said this on January 16, 2017 at 4:48 am |